Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travelers

History. We now stand on one of the most profoundly interesting spots in the world. It was near this spot that David erected an altar (2 Sam. xxiv. 25). This was also the site selected by Solomon for the erection of his palace and the Temple. The formation of the ground seems to indicate more particularly the site of the present 'Dome of the Rock' as the position of the Temple; and indeed, when we consider the tenacity with which religious traditions have clung to special spots in the East, defying all the vicissitudes of creeds down to the present day, it seems highly probable that the present ideal central point, the sacred rock, must have been of especial sanctity from the earliest period. This rock was perhaps the site of the altar of burnt offerings, while the Temple itself stood to the W. of it. Solomon's Temple consisted of the actual inner Temple with the 'sanctuary' and the 'holy of holies' within it, the latter to the W. of the former, and in the form of a cube. The sanctuary was approached by a porch, in front of which, in the court, stood the altar of burnt offerings, the 'molten sea' (a large basin), the 'bases', and the lavers. For many years after Solomon's death the work was continued by his successors.

The Second Temple, which the Jews erected under very adverse circumstances after their return from exile, was far inferior in magnificence to its predecessor, and no trace of it now remains. All the more magnificent was the Third Temple, that of Herod, of which much has been preserved. The erection of this edifice was begun in B.C. 20, but it was never completely carried out in the style originally projected. We possess an account of this Temple by Josephus (Ant. xv. 11; Bell. Jud. i. 21, 1 ; v. 5), but as his work was written at Rome, and at a later period, his description is often deficient in clearness and precision.

To this period belong in the first place the imposing substructions on the S. side, in which direction the Temple platform was at that time much extended, while the Asmoneans had enlarged it towards the N. The still visible enclosing walls, with their huge stones, which had perhaps partly belonged to the earlier edifice, were doubtless also the work of Herod (further details, see p. 56). Around the margin of the grand platform ran colonnades , consisting of a double series of monoliths, and enclosing the whole area. Solomon's Porch (St. John x. 23) is placed by some authorities on the S. side, but by others with greater probability on the E. side. On the S. side the colonnade was quadruple, and consisted of 162 columns. On the W. side there were four, on the S. side two gates, and the vestibules were approached by stairs leading through corridors. It is uncertain whether there was a gate on the E. side. The colonnades enclosed the great court of the Gentiles , which always presented a busy scene. A balustrade enclosed a seoond court, lying higher, where notices were placed prohibiting all but Israelites from entering this inner entrance-court. (A notice of this kind in Greek, closely corresponding with the description given by Josephus, was found.) A section of the fore-court of the Israelites was specially set apart for the women, beyond which lay the court of the priests with the great sacrificial altar of unhewn stones. A deep, richly decorated corridor now ascended by twelve steps to the 'sanctuary', or 'holy place' strictly so called, whioh occupied the highest ground on the Temple area. The sanctuary was surrounded on three sides (S., W., N.) by a building 20 ells in height, containing 3 stories, the upper story rising to 10 ells beneath the top of the 'holy place', so that space remained for windows to light the interior of the sanctuary. Beyond the gate was the curtain or 'veil', within which stood the altar of incense, the table with the shew-bread, and the golden candlestick. In the background of the 'holy place' a door led into the small and dark 'holy of holies', a cube of 20 ells. — The Temple was built of magnificent materials, and many parts of it were lavishly deeorated with plates of gold. The chief facade of the edifice looked towards the E. , while on the N. side two passages led from the colonnades of the Temple to the castle by which the sacred edifice was protected. It was thence that Titus witnessed the burning of the beautiful building in the year A. D. 70. The colonnades had already been burned down by the Jews themselves , but the huge substructions of massive stone which supported the Temple could not be destroyed.

On the site of the ancient Temple Hadrian erected a large temple of Jupiter, containing a statue of that god and one also of himself (or of Castor and Pollux?). It was adomed with twelve columns. The earliest pilgrims found the temple and the equestrian statue of the emperor still standing, near a 'rock pierced with holes'. There is a great controversy as to what buildings were afterwards erected on this site. We are informed by Arabian authors that 'Omar requested the Christian patriarch to conduct him to this spot, where the ancient Temple of Solomon had once stood, and that he found it covered with heaps of rubbish which the Christians had thrown there in derision of the Jews.

The present dome is a structure of the Arabian period. In the interior of the building there is an inscription in the oldest Arabic character (Cufic), recording that 'Abdallah el-Imâm el-Mâmûn, prince of the faithful . erected this dome in the year 72'. But as Mâmûn was not born till the year 170 after the Hegira, it must be assumed that the words 'el-Mâmûn', as moreover the different colour of this part of the inscription tends to show, were erroneously substituted at a later period for 'el-Melik', a splendour-loving Omayyade khalîf to whom Arabian historians attribute the erection of the building.

Abd el-Melik was moved by political considerations to erect a sanctuary on this spot. The Omayyades, who sprang from the ancient aristocracy of Mecca, were the first princes who thoroughly appreciated the political advantages of the new religion. Accordingly, when revolts broke out against the khallfs, they chose Jerusalem as the site of a new sanctuary which should rival that of the Ka'ba. The inscription on the doors (p. 40) may justify us in regarding the Khalif Mâmûn as the restorer of the building. A further restoration was carried out in the year 301 of the Hegira (A.D. 913). — The plan of the building is certainly Byzantine, for which reason Prof. Sepp supposed it to be an old church of Justinian, a second Hagia Sophia.

That the style resembles the Byzantine need however not surprise us, for the Arabs of that period did not yet understand the art of building. On the contrary it would have been surprising if they had not found it necessary to borrow their architecture from the Greeks.

The polygonal or round construction is found in the S, Stefano Rotondo at Rome as early as the end of the 5th century. But the Dome of the Rock differs essentially in not requiring any apse, as the building had to be adapted to the Holy Rock in its centre, just as the Church of the Sepulchre to the Holy Sepulchre is the only difference between the Dome of the Rock and the Church of the Sepulchre is that the former is polygonal, the latter round. The Church of the Sepulchre may therefore be considered as the model for the mosque.

Mohammed himself had evinced veneration for the ancient Temple. Before he had finally broken off his relations with the Jews, he even commanded the faithful to turn towards Jerusalem when praying. The Koran also mentions the Mesjîd el-Aksa (i. e. the mosque most distant from Mecca) in a famous passage in Sûreh. xvii. 1 : 'Praise be to him (God), who , in order to permit his servant to see some of our miracles, conveyed him on a journey by night from the temple el-Harâm (the Ka'ba at Mecca) to the most distant temple, whose precincts we have blessed'. Mohammed thus professes to have been here in person; to this day the Harâm of Jerusalem is regarded by the Muslims as the holiest of all places after Mecca; and it is on this account that they so long refused the Christians access to it. The Jews, on the other hand, have never sought this privilege, as they dread the possibility of committing the sin of treading on the 'holy of holies'.

literature: Vogué, Le Temple de Jérusalem, Paris 1884. Schick, Beit el-Makdas, Jerusalem 1887; Die Stiftshiitte, der Tempel in Jerusalem, und der Tempelplatz der Jetztzeit, Berlin 1895. Chipiez ei Perrot, Le Temple de Jerusalem, Paris 1889.

No one should omit to visit the Harâm. A small party had better be formed for the purpose. The consulate, on being applied to, procures the necessary permission from the Turkish authorities, who provide one or more soldiers as attendants, and the kawass of the consulate also accompanies the party. Each person pays 12 piastres to the kawass, that being the fee due to the shekh, who accompanies the party. A boy should also be taken from the hotel to carry slippers, and afterwards the boots of the visitors, when these are removed (fee 1-2 piastres from each person). After the visit is over, the party pays a fee to the soldier who accompanies them, and to the kawass of the consulate, at least 16 piastres each} or more according to the size of the party. A bright day should if possible be selected for the visit (but not Friday), as the interior of the building is somewhat dark. On certain days the Muslim women walk in the court of the mosque, and are apt to inconvenience visitors.

"We shall first direct our attention to the interior of the Harâm esh-Sherîf. The Temple platform occupies the S.E. quarter of the modern town. The Harâm is entered from the town on the W. side by seven gates, viz. (beginning from the S.) the Bâb el-Maghâribeh (gate of the Moghrebins), Bâb es-Silseleh (chain-gate), Bâb el-Mutawaddâ , or Matara (gate of ablution), Bâb el-Kattânîn (gate of the cotton-merchants), Bâb el-Hadîd (iron gate), Bâb en-Nâzir (custodian's gate), also called Bâb el-Habs (prison gate), and lastly, towards the N. , Bâb es-Serâi (gate of the seraglio), also called the Bâb el-Ghawânimeh (named after the family of Beni Ghanim). — The large area scattered with buildings forms a somewhat irregular quadrangle. The W. side is 536 yds., the E. 518 yds., the N. 351 yds., and the S. 309 yds. in length. The surface is not entirely level, the N.W. corner being about 10 ft. higher than the N.E. and the two S. corners. The W. and N. sides of the quadrangle are partly flanked with houses, with open arcades below them, and the E. side is bounded by a wall. Scattered over the entire area are a number of Mastabas (raised places) with a Mihrâb (prayer-recess; p. xl) and used as places of prayer; there are also numerous Sebîl (fountains) for the religious ablutions. — Visitors are usually conducted first through the cotton-merchants' gate past the Sebîl Kâit Bei (p. 46) to the Mehkemet Dâûd (p. 45).

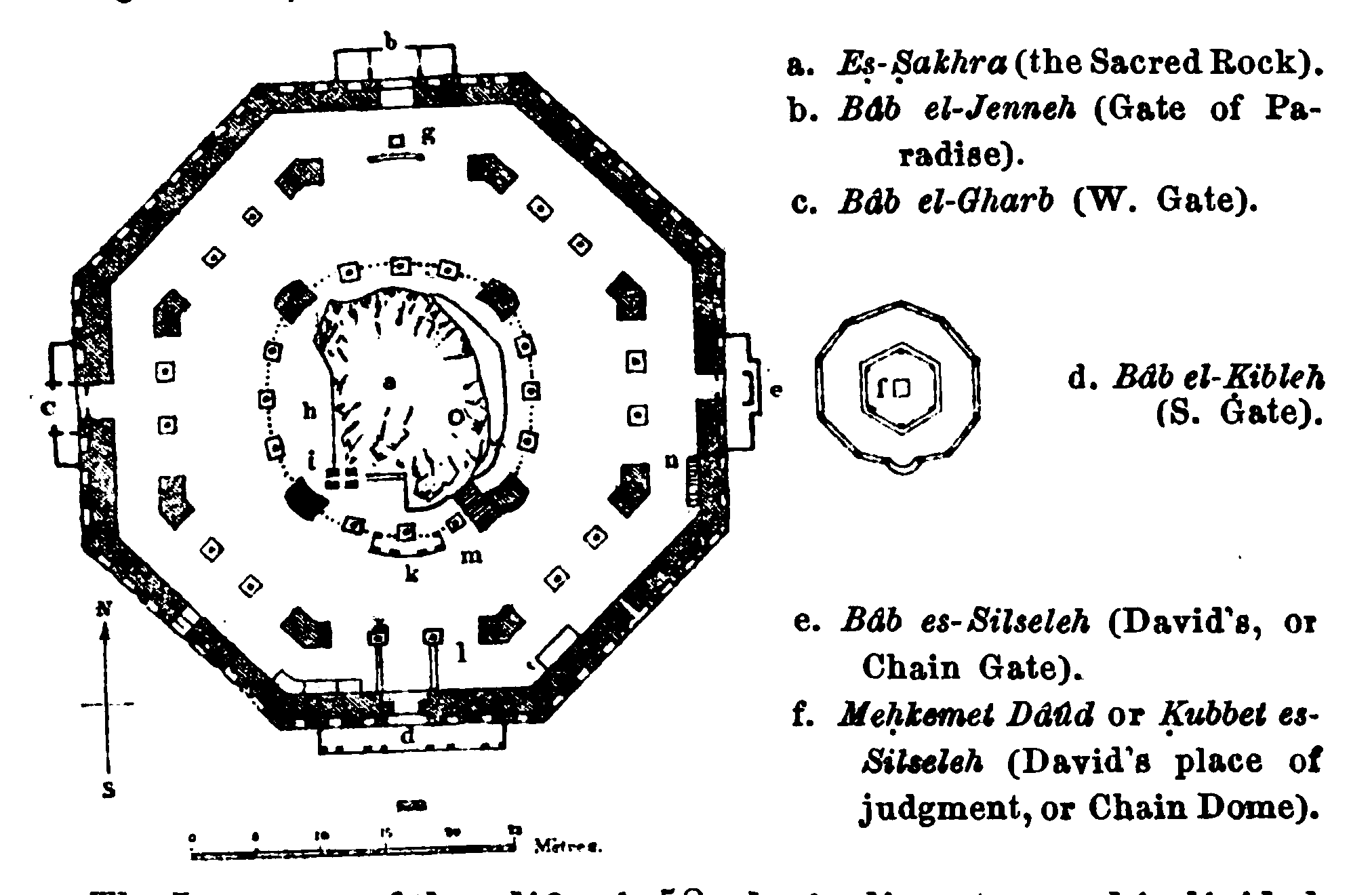

The "'Dome of the Rock, or Kubbet es-Sakhra, stands on an irregular platform 10 ft. in height, approached by three flights of steps from the W. , two from the S. , one from the E. , and two from the N. side. The steps terminate in elegant arcades, called in Arabic Mawâzin, or scales, because the scales at the Day of Judgment are to be suspended here. These arcades, which materially enhance the beauty of the exterior, are imitated from those of the fore-court of the Jewish Temple, as they form to a certain extent the entrance to the sanctuary. This upper platform, therefore, which is paved with fine slabs of stone, may only be trodden upon by shoeless feet. From this point we survey the whole arrangements of the Harâm. Besides the larger buildings , a number of smaller structures are scattered over the extensive area. The ground is irregularly planted with trees, chiefly cypresses, and is of a reddish brown colour, except in spring when it is green after rain.

he Kubbet es-Sakhra is a large and handsome Octagon. Each of the eight sides is 66 ft. 7 in. in length and is covered externally as far as the window sill with porcelain tiles, and lower down with marble. The whole building was formerly covered with marble, the porcelain incrustation having been added by Soliman the Magnificent in 1561. The effect of these porcelain tiles, which are manufactured in the Persian style (Kâshâni), is remarkably fine, the subdued blue contrasting beautifully with the white, and with the green and white squares on the edges. Passages from the Koran, beautifully inscribed in interwoven characters , run round the building like a frieze. Each tile has been written upon and burned separately. In each of those sides of the octagon which are without doors are seven, and on each of the other sides are six windows with low pointed arches , the outer pair of windows being walled up in each case. The incrustation on the W. side, having become much dilapidated, has been partly taken down and restored. During the course of this work some ancient round arches were discovered, and it turned out that the present form of the windows is not older than the 16th century, and that formerly seven lofty round-arched windows with a sill and smaller round-arched openings were visible externally on each side. A porch is supposed to have existed here formerly. Mosaics have also been discovered between the arcades. The stones, as the visitor may observe on the W. side, are small, irregular, and jointed with no great accuracy.

The Gates, which face the four cardinal points of the compass, are square in form, each being surmounted with a vaulted arch. In front of each entrance there was originally an open, vaulted porch, borne by four columns. Subsequently the spaces between them were built up. The S. Portal, however, forms an exception, as there is here an open porch with eight columns. The W. entrance is a modern structure of the beginning of the present century. The N. Portal is called Bâb el-Jenneh, or gate of paradise; the W., Bâb el-Gharb, or W. gate; the S., Bâb el-Kibleh, or S. gate, and the E., Bâb Dâûd or Bâb es-Silseleh, gate of David, or chain gate. On the lintels of the doors are inscriptions of the reign of Mâmûn, dating from the year 831, or 216 of the Hegira. The twofold doors (which are usually open] , dating from the time of Soliman , are of wood, covered with plates of bronze attached by means of elegantly wrought nails, and have artistically executed locks.

The Sacred Rock

The Interior of the edifice is 58 yds. in diameter, and is divided into three concentric parts by two series of supports. The First Series, by which the outer octagonal aisle is formed , consists of eight piers and sixteen columns, two columns being placed between each pair of the six-sided corner piers. The shafts of the columns are of marble, and differ in form, height, and colour. They have all been taken from older edifices, some of them probably from the temple of Jupiter mentioned above. The capitals are likewise of very various forms, dating either from the late Romanesque or the early Byzantine period, and one of them is even said to have borne a cross. To secure a uniform height of 20 ft., large Byzantine blocks which support small arches are placed above the capitals. These blocks are connected by so-called 'anchors', or broad beams consisting of iron bars with wooden beams beside and beneath them. These are covered beneath with copper-plates in repousse". On the beams lie marble slabs which project like a cornice on the side next the external wall, but are concealed by carving on that next the rotunda. Under the ends of the beams are placed foliated enrichments in bronze. While the pilasters are covered with slabs of marble, dating from the period of Soliman, the upper part of the wall is intersected by arches and adorned with mosaics. The rich and variegated designs of these mosaics are not easily described. They oonsist of fantastic lines intertwined with striking boldness, and frequently of garlands of flowers, and are all beautifully and elaborately executed. Above them Is a broad blue band , bearing very ancient Cufic inscriptions in gold letters. These are verses of the Koran bearing reference to Christ, and seem to indicate that the founder was desirous of emphasising the new position of the Muslims with regard to the Christians of that period : —

Sûreh xvii. Ill : Say—Praise be to God who has had no son or companion in his government, and who requires no helper to save him from dishonour; praise him. Sûreh lvii. 2: He governs heaven and earth, he makes alive and causes to die , for he is almighty. Sûreh iv. 169 : O ye who have received written revelations , do not he puffed up with your religion, but speak the truth only of God. The Messiah Jesus is only the son of Mary, the ambassador of God, and his Word which he deposited in Mary. Believe then in God and his ambassador, and do not maintain there are three. If you refrain from this it will be better for you. God is One, and far be it from him that he should have had a son. To him belongs all that is in heaven and earth, and he is all-sufficient within himself. Sûreh xix. 34 et seq. : Jesus says — 'Blessings be on me on the day of my birth and of my death, and of my resurrection to life. He is Jesus, the son of Mary, the word of truth, concerning whom some are in doubt. God is not so constituted that he could have a son; be that far from him. When he has resolved upon anything he says 'Let it be, and it is. God is my Lord and your Lord ; pray then to him ; that is the right way.

Here, too, is an inscription of great historical importance, which we have already mentioned at p. 38.

A second aisle is formed by a Second Series of supports arranged in a circle, on which also rests the dome. These supports consist of four massive piers (whose inner and outer sides follow the circumference of the circle) and twelve monolithic columns (those in the middle being the thinnest). These columns also are antique; their bases were covered with marble in the 16th cent., but beneath the marble they are quite different from each other. The arches above them rest immediately on the capitals. — The dome rests first on a drum, which is richly adorned with mosaics. These are divided by a wreath into two sections, in the upper of which are placed 16 windows. The mosaics are of different periods. Most of them represent vases of flowers, among which are grapes and ears of corn on a gold ground. The Byzantine artists who executed them were prohibited by the laws of El-Islâm from representing figures, but perhaps used these devices as emblems of the Last Supper. All the mosaics are composed of small fragments of coloured glass, and date from the 10th and 11th centuries, when this art had probably entered upon a new phase in the East.

The Dome which rises on these supports is made of wood : its height (from the ground) is 98 ft., to which the crescent adds 16 ft. more ; the vault of the dome is 37 1/2 ft. high inside and only 66 ft. in diameter, it is consequently a surmounted hemisphere. Externally, its form is more elliptical. Its framework is double, the space between the inner and outer boarding, the ribs of which are connected by braces, varying from 2 ft. to 6 ft, in width. Steps lead up to the apex of the dome, whence a trapdoor gives access to the crescent. The upper part of the external frame is boarded and covered with lead. Within, it is covered with tablets of wood nailed to the roof-tree, coloured blue, and richly adorned with painted and gilded stucco. According to the inscriptions, the dome was constructed in 1022 (Hakim, p. lxvi), the old dome having fallen in six years previously. The decorations of the interior are of the period of Saladin, who ordered them to be restored immediately after he had taken the holy city from the Franks (1189). They were restored, or rather the colours were revived, in 1318 and 1830.

— The Window Openings are closed with thick slabs or plates of plaster perforated with holes and slits of various shapes, wider inside than outside. These perforations have been glazed on the outside with small coloured glass plates, forming a variety of designs, and affixed to the plaster by cramps. The effect of the colours is one of marvellous richness, but the windows shed a dim light only on the interior, and the darkness is increased, firstly by regular glass windows framed in cement, secondly by a wire lattice, and lastly by a porcelain grating placed over them outside to protect them from rain. The lower windows bear the name of Soliman and the date 935 (i. e. 1528). The walls between the windows were originally covered with mosaics, like those in the drum, but the Crusaders substituted paintings, of which we still possess a description. Saladin caused the walls to be covered with marble, and they were restored by Soliman.

— The Pavement consists of marble mosaic and marble flagging which is covered in places with straw-mats.

The Crusaders converted the dome of the rock into a 'Templum Domini', adorned it with figures of saints, and placed a large gilded cross on its summit. On the sacred rock stood the altar. The surface of the rock was paved with marble, and a number of steps hewn in the rock led up to the altar. Distinct traces of these are still visible. The choir was enclosed by two walls , part of one of which is still preserved on the S.W. side. A relic of the period of the Crusaders (end of the 12th cent.) is the large wrought iron screen with four gates (of French workmanship), placed on a stone foundation between the columns of the inner ring (el-kafas) and thus enclosing the sacred rock. Candles were once placed upon its spikes. The rock is now further enclosed by a coloured wooden screen , but space is left to walk round between it and the iron screen. The best view of the rock is obtained from the high bench by the gate of the screen to the N.W. The gilded chain which hangs from the summit of the dome is modern. It used to hold a chandelier, now broken to pieces.

We now proceed to inspect the Holy Rock itself. It is 58 ft. long and 44 ft. wide, and rises about 6 1/2 ft- above the surrounding pavement. The earliest reference to it is found in the Talmud, or Jewish tradition. As in other sanctuaries of antiquity , such as Delphi, the stone is said to cover the mouth of an abyss with a sub terranean torrent, the waters of which were heard roaring far beneath. According to Jewish tradition Abraham and Melchizedek sacrificed here, Abraham was on the point of slaying Isaac here, and the rock is said to have been anointed by Jacob. As it was regarded as the central point of the world, the Ark of the Covenant is said once to have stood here, to have been afterwards ooncealed here by Jeremiah (but according to 2 Mace. ii. 5 in a cave in Mount Nebo), and still to lie buried beneath the sacred rock. On this rock also was written the 'shem', the great and unspeakable name of God. Jesus, says tradition, succeeded in reading it, and he was thus enabled to work his miracles. — The rock now before us cannot be identified with the ' eben shatyâ' , or stone of foundation, of Jewish tradition, if only on account of its size ; it is much too large ever to have stood in the 'holy of holies'. The probability is that the great sacrificial altar stood here, and traces of a channel for carrying off the blood have been discovered on the rook. Excavations, if permitted, would probably show that the natural hollow under the stone goes deeper into the earth and is really a cistern.

The Muslims adopted and improved upon this tradition about the rock, as they did with so many other already existing Jewish traditions. According to them the stone hovers over the abyss with out support. "When we descend by eleven steps on the south side (PI. m) by the pulpit (k) to the cavern beneath the rook we see a support, and all round the rock resting on a whitewashed wall. The hollow sound heard by knocking the wall is not due to any cavity behind it, but to the mortar peeling off from the rook. In this cavern the cicerone points out the places where David and Solomon (small altars), Abraham (left) and Elijah (N.) were in the habit of praying. Mohammed has also left the impression of his head on the rooky ceiling. The guide knocks on a round stone plate almost in the middle of the floor; there is evidently a hollow underneath. The Muslims maintain that beneath this rock is the Bir el-Arwfâh, or well of souls , where the souls of the deceased assemble to pray twice weekly. Some say that the rook came from paradise, and that it rests upon a palm watered by a river of paradise; beneath this palm are Asia, wife of Pharaoh, and Mary. Others maintain that these are the gates of hell. At the last day the Ka'ba of Mecca will come to the Sakhra, for here will resound the blast of the trumpet which will announce the judgment. God's throne will then be planted upon the rock. Mohammed declared that one prayer here was better than a thousand elsewhere. He himself prayed here, to the right of the holy rook, and from hence he was translated to heaven on the back of El-Burâk, his miraculous steed. It was in the course of his direct transit to heaven that his body pierced the round hole in the ceiling of the rock which we still observe. On this occasion, moreover, the rook opened its mouth, as it did when it greeted 'Omar, and it therefore has a 'tongue', over the entrance to the cavern. As the rock was desirous of accompanying Mohammed to heaven, the angel Gahriel was ohliged to hold it down, and the marks of his hand are still shown on the W. side of the rock (Pl.h).

A number of other marvels are shown. In front of the N. entrance there is let into the ground a slab of jasper (Balatat el-Jenneh, PI. g), into which Mohammed drove nineteen golden nails; a nail falls out at the end of every epoch , and when all are gone the end of the world will arrive. One day the devil succeeded in destroying all but three and a half , but was fortunately detected and stopped by the angel Gabriel. The slab is also said to cover Solomon's tomb. — In the S.W. comer (Pl.i), under a small gilded tower , is shown the footprint of the prophet , which in the middle ages was said to be that of Christ. Hairs from Mohammed's beard are also preserved here , and on the S. side are shown the banners of Mohammed and 'Omar. — By the prayer-niche (PI. 1) adjoining the S. door are placed several Korans of great age, but the custodian is much displeased if they are touched by visitors.

Outside the E. door of the mosque, the Bâb es-Silseleh, or Door of the Chain (which must not be confounded with the entrance-gate of the same name, p. 39) rises the Kubbet es-Silseleh, 'dome of the chain', also called Mehkemet Dâûd, David's place of judgment. According to Muslim tradition, a chain was once stretched across this entrance by Solomon, or by God himself. A truthful witness could grasp it without producing any effect, whereas a link fell off if a perjurer attempted to do so. The Muslims declare that this dome of the chain afforded a model for the dome of the rock , but that is very improbable. This elegant little structure consists of two concentric rows of columns, the outer forming a hexagon, the inner an endecagon. This remarkable construction enables all the pillars to be seen at one time. The shafts, bases, and columns, which differ greatly from each other, are chiefly in the Byzantine style, and they have all been taken from older buildings. The pavement consists of beautiful mosaic , and on the S. side (facing Mecca) there is a handsome recess for prayer. Above the flat roof rises a hexagonal drum surmounted by the dome, which is slightly curved outwards. The top is adorned with a crescent* The mosaics are of the same date as those of the Sakhra and the -plan of the entire building seems to be of that period.

About 20 yds. to the N. W. of the Sakhra rises the Kubbet el-Mi'râj, or dome of the ascension, erected to commemorate Mohammed's miraculous nocturnal journey to heaven. According to the inscription, the structure was rebuilt in the year 597 of the Hegira (i. e. 1200), 13 years after Jerusalem had been recaptured by the Muslims. It is interesting to observe the marked Gothic character of the windows, with their recessed and pointed arches borne by columns. Close by is an ancient font, now used as a water trough. Farther towards the N.W. is the Kubbet en-Nebi (dome of the prophet), a modern looking building over a subterranean mosque built in the rock. This mosque is not shown to visitors. There is also a very small building called the Kubbet el-Arwah (dome of the spirits), which is interesting from the fact that the bare rock is visible below it. Beside the flight of steps on the N.W. leading down from the terrace, is the Kubbet el-Khidr (St. George's dome). Here Solomon is said to have tormented the demons. In front of the mosque are two red granite pillars.

More to the S. we observe below, between us and the houses encircling the Harâm, an elegant fountain-structure, called the Sebîl Kâit Bei, which, according to the inscription, was erected in the year 849 of the Hegira (1445) by the Mameluke sultan Melik el-Ashraf Abu'n-Naser Kâit-Bei. Above a small cube, the corners of which are adorned with pillars, rises a cornice and above this an octagonal drum with sixteen facets ; over this again a dome of stone, the outside of which is entirely covered with arabesques in relief. At the S.E. angle of the terrace there is finally an elegant Pulpit in marble , called the 'summer pulpit' or Pulpit of Kâdi Borhâneddîn from its builder (d. 1456). A sermon is preached here every Friday during the fast of the month Ramadan. The horseshoe arches supporting the pulpit, and the pulpit itself with its slender columns, above which rise arches of trefoil form , present a fine example of genuine Arabian art.

The other buildings on the terrace are unimportant, consisting of Koran schools and dwellings. Objects of greater interest are the cisterns with which the rock is deeply honeycombed. Towards the S.W. of the mosque in particular there are many such cisterns of great antiquity, some of them connected with each other in groups, one below the other. These cisterns are not visible from the surface, but the attention is attracted by the numerous holes through which the water is drawn.

We bestow another glance upon the Sakhra. This magnificent building produced a powerful impression on the Franks of the middle ages, and it was popularly believed to be the veritable Temple of Solomon. The society of knights founded here was accordingly called the order of the Temple , and they adopted the dome of the sacred rock as part of their armorial bearings. The Templars, moreover, carried the plan of the building to Europe; London, Laon, Metz, and several other towns still possess churches in this style. The polygonal outline of this mosque is even to be seen in the background of Raphael's famous Sposalizio in the Brera at Milan.

Passing the pulpit, and descending a flight of twenty-one steps towards the S. , we soon reach a large round basin (el-Kâs), once fed by a conduit from the pools of Solomon (p. 55). — To the E. of this, in front of the Aksa, there is a cistern hewn in the rocks known as the Sea, or the King's Cistern, which was also supplied from Solomon's pools. This Teservoir is mentioned both by Tacitus and the earliest pilgrims. It was probably constructed before Herod's time. It is upwards of 40ft. in depth, and 246 yds. in circumference. In summer it contains but little water, and there are now very few openings communicating with it from the surface. A staircase -hewn in the rock descends to these remarkably spacious vaults, which are supported by pillars of rock. Immediately before the portal of the Aksa mosque is another cistern under the mosque itself, called the Btr el-Waraka, or leaf fountain. A man of the tribe of Temim (in N.E. Arabia), a companion of 'Omar, having once let his pitcher fall into this cistern , descended to recover it, and discovered a gate which led to orchards. He there plucked a leaf, placed it behind his ear, and showed it to his friends after he had quitted the cistern. The leaf came from paradise and never faded. Other persons, however, who descended for the purpose of visiting the Elysian orchards, were unable to find them.

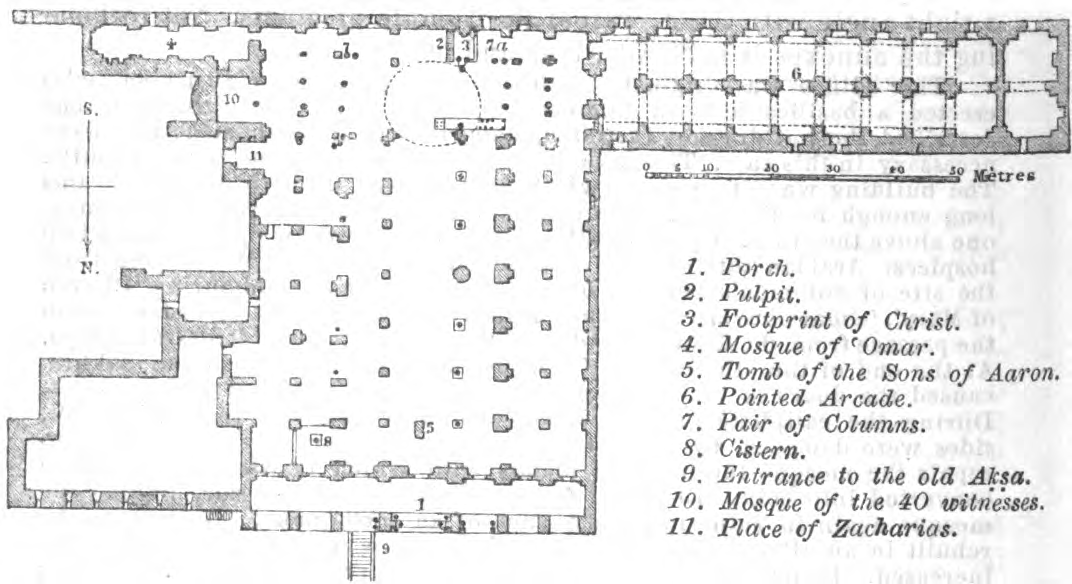

The mosque E1-Aksa. During that part of Mohammed's career when he derived most of his 'revelations' from Jewish sources, he declared the Aksa, the 'most distant' shrine, to be an ancient holy place of Proto-Islam, tradition making him say that it was founded only forty years after the foundation of the Ka'ba by Abraham. The mosque is at the present day a basilica with nave and triple aisles (with subsidiary buildings), the principal axis of which forms a right angle with the S. wall of the Temple precincts. Not reckoning the annexes it is 88 yds. long and 60 yds. wide.

The edifice was originally founded by the Emperor Justinian, who erected a basilica here in honour of the Virgin. Proeopius, who has described the buildings of Justinian, states that artificial substructions were necessary in this case. The nave, in particular, rests on subterranean vaults. The building was of so great width that it was difficult to find beams long enough for the roof. The ceiling was borne by two rows of columns, one above the other. In front of the church there were two porches and two hospices. Arabian authors state that the Khalîf 'Omar on descending from the site of Solomon's Temple, offered prayers in the neighbouring 'Church of Mary'. `Omar converted the church into a mosque in accordance with the passage from the Koran already mentioned (p. 38) named it Mesjid el-Aksa. At the end of the 7th century, `Abd el-Melik, the founder of the Sakhra, caused the doors of the Aksa to be overlaid with gold and silver plates. During the caliphate of Abu Ja'far el-Mansur (768-775) the E. and W. sides were damaged by an earthquake, and in order to obtain money to repair the mosque the precious metals with which it was adorned were converted into coin. El-Mehdi (775-795), Mansur's successor, finding the mosque again in ruins in consequence of an earthquake, caused it to be rebuilt in an altered form, its length being now reduced, but its width increased. In 1060 the roof fell in, but was speedily repaired. Such is the account given by Arabic authors, whence we may infer that little of the original building is now left (probably only a few capitals under the dome and one in the left aisle). The columns of the nave date from Justinian's basilica, but they have been so shortened as now to appear clumsy. All the aisles were formerly vaulted, now only the two outer ones on each side are so.

he Porch (PI. 1), in its present form, consists of seven arcades leading into the seven aisles of the building. It was erected by Melik el-Mu'azzam 'Isa, a nephew of Saladin, in 1236, and was restored at a later period ; the roof is not older than the 15th century. The central arcades show an attempt to imitate the Gothic style of the Franks, but the columns, capitals, and bases do not harmonise, as they are taken from ancient huildings of different styles.

The original arrangements of the Interior, which should be visited first, still present a striking appearance. The nave and two adjacent aisles, in which the plan of the old basilica is recognisable, are the only parts which are strictly ancient. The W. aisle was probably once walled up , and on the E. side lay the court of the mosque, as at Fostât in Egypt, and at Damascus. The great transept with the dome, which perhaps belongs to the restoration of El-Mehdi, gave the edifice a cruciform shape. It was probably the same prince, who, in order to obliterate the form of the cross, added two lower Aisles on the E. and W. sides of the mosque respectively, and for this purpose the lateral walls of the building had to be broken through. In their present form, however, these four outer aisles belong to a later restoration. The piers are of a simple square form, and the vaulting is pointed.

The Nave and its two immediately adjoining aisles are very superior in style to the other aisles just mentioned, and possess far greater individuality and uniformity. The capitals, some of which still show the form of the acanthus leaf, are Byzantine, and perhaps date from the 7th century. The seven arches which rise above the columns are wide and pointed, and therefore doubtless of later date ; and here again we find the wooden 'anchor', or connecting beam be tween the arches, which is peculiar to the Arabs. Above the arches is a double row of windows , the higher of which look into the open air, the lower into the aisles. The nave and central aisles, and the transept also, are still roofed with beams, as was the case in basilicas. The nave and central aisles are farther remarkable for the shape of their roofs, which terminate externally in gables both at the ends and sides.

The Transept , like the rest of the edifice , is constructed of old materials. The antique columns are by no means uniform like those of the nave, but vary in material, in form, and even in height. According to an inscription, this part of the building was restored by Saladin in 583 (1187). To the same period belong the fine mosaics on a gold ground in the drum of the dome, which, according to Arabian accounts, Saladin obtained from Constantinople, and also the prayer-niche on the S. side, flanked with its small and graceful maxhle columns. The coloured band which runs round the wall of this part of the mosque, about 6 ft. from the ground, consists of foliage, in Arabian style. The Cufic inscriptions are texts from the Koran.

The Dome is constructed of wood, and covered with lead on the outside; within, it is decorated in the same style as the dome of the Sakhra. An inscription records the name of the Mameluke sultan Mohammed ibn Kilaun as the restorer (or perhaps founder) of these decorations in 728 (1327). Some of the windows of the mosque are filled with stained glass of the same period (16th cent.) as that in the Sakhra, but inferior to it. The wretched paintings on the large arch of the transept were executed by an Italian during the present century. — Adjoining the prayer -niche we observe a Pulpit (PI. 2) beautifully carved in wood. The details of the decoration are admirable. The ascent to the pulpit, as well as the pointed structure itself, is inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl. It was executed in 564 (1168) by an artist of Aleppo by order of Nûreddîn, and was placed here by Saladin on the restoration of the Aksa. On the stone behind this pulpit is shown the Footprint of Christ (PI. 3), which appears to have been seen by Antonio of Piacenza, one of the earliest pilgrims, at or near this very spot. On each side of the pulpit, we observe a pair of columns close together (PI. 7 and 7a). The cicerone declares that persons who are not born in lawful wedlock cannot pass between the columns, while others say that no one can enter heaven if he cannot pass between them. (There is a similar pair of columns in the mosque of 'Amru at Old Cairo.) An iron screen has now been fixed between them.

Subsidiary Buildings. A prolongation of the transept towards the W. is formed by a double colonnade with a vaulting of pointed arches (PI. 6), but the pilasters are of rather rough workmanship. All this part of the building was erected by the Knights Templars, who used it as an armoury or something of that sort. The Aksa was specially allotted to the Templars; they called it porticus, palatium, or templum Salomonis; the knights lived here and in the lower chambers of this corner of the Harâm, the windows looking out to the S. on the mountain slope. This part of the building is now the women's mosque, the `White Mosque'. — The modern addition to the mosque on the S.E. side is a bare uninteresting building with a prayer-niche (PI. 4), where the proper Mosque of 'Omar is said once to have stood, the dome of the rock having heen erroneously called so by the Franks. A similar addition is situated to the N. ; the greater part of it (to th eS.) is the apse of an old Christian church, now converted into the Mosque of the 40 Witnesses (PI. 10), and to the N. of it (PI. 11) is the place where Zacharias is said to have heen slain. There is a handsome rose-window here dating from the times of the crusaders. A fine stone slab in the pavement of the nave, not far from the entrance, used to be shown as the tomb of the Sons of Aaron (PI. 5), but it is now covered with mats.

On emerging from the central portal we find a staircase on the right, which descends by eighteen steps to the Vaults below the Aksa. These are formed by a double series of arches resting on piers. The central series lies exactly under the arcades which form the E. side of the nave of the basilica, which is perhaps a proof that the original basilica only extended thus far. The substructions in their present form are not ancient, the brickwork of the E. wall, for instance, being of late date, but they occupy the site of the original Byzantine foundations. Towards the S. end eight more steps descend to a vault, with four flat arches resting in the centre against a short and thick monolithic column covered with whitewash, the capital of which, with its stiff acanthus, or rather palm leaves, appears to be Byzantine. Near the end of the partition wall a three-quarter column is visible. The old Double Gate to the S. is still in complete preservation; the three columns are composed of very large stones of the Jewish period. The lintels of the gates are still in position ; but the eastern one is broken, and both are supported by columns added at a later time ; on the inside they are whitewashed , but on the outside they are still partly visible and are ornamented with well squared , tablet-like stones. The entire space was once a porch belonging to the Double Gate, now walled up, but was closed in and vaulted in the Byzantine manner, probably at the period of the erection of the church of St. Mary. This double gate is supposed to be the 'Huldah Portal' of the Talmud, and we may therefore assume that Christ frequently entered the Temple from this point, particularly on the occasion of festivals. It is now a Muslim place of prayer, and is therefore covered with straw matting.

Whether there are vaults under the S. W. Corner of the Harâm is a question that is still unanswered, but probably there are. 'Through a children's school entrance may be gained to an interesting subterranean building and to the huge square block by Barclay's gate (p. 56).

The whole of the S.E. Corner of the Harâm is supported by artificial substructions, the sole object of which was to afford a level surface. The entrance to them is near a small arcade in the S.E. corner of the Temple precincts. Descending thirty-two steps, we enter a small Muslim oratory, where a horizontal niche, surmounted by a dome borne by 4 small columns, is pointed out as the 'Cradle of Christ', under which name it was also known in mediaeval times. In pre -Islamic times the 'Basilika Theotokos' (of the Mother of God) or 'Maria Nova' was here. This tradition seems to have been founded on an old custom of Hebrew women to resort hither to await their confinement. According to the legend , this was the dwelling of the aged Simeon , and the Virgin spent a few days here after the Presentation in the Temple.

From this point we descend into the spacious substructions, known as 'Solomon's Stables'. The Arabs attribute them to the agency of demons , but in their present form they are an imitation (probably Arabian) of similar older substructions which once occupied the same spot. The piers are chiefly composed of ancient drafted stones. Many Jews sought refuge in these vaults during their struggle against the Romans, and there is other evidence that substructions of the kind existed at an early period in this corner. In the middle ages the stables of the Frank kings and of the Templars were here, and the holes in the pillars by which they tethered their horses may still be seen. The vaults extend 91 yds. from E. to W., and 66 yds. from S. to N. There are altogether 13 vaults of unequal length and breadth. The arches, in the shape of a rather elongated semicircle (about 30 ft. high), are borne by 88 columns in 12 parallel rows. Opposite the sixth row (from the stairs) there is a small closed door in the S. wall called the 'Single Gate' (near which is the so called 'Cradle of David'). To the extreme W., separated by a wall from the other vaults, there is another triple series of substructions, which terminate towards the S. in a Triple Oate. Of this ancient Temple gate, which was built in the same style as the double gate already described, the foundations only are preserved. The gates themselves are blocked up. The arches are of somewhat elliptical form. The whole porch was about 53 ft. in width and 25 ft. in height. For the exterior comp. p. 58. Fragments of columns are also observed built into the walls here, and an ancient column is seen in the wall about 20 yds. to the N. of the gate. Farther on, about 132 yds. from the S. wall, the style in which the gallery is built begins to alter, and the upper part becomes more modern. The substructions extend to the N., over a large rocky cistern, beyond the Aksa mosque. (We observe here the huge roots of the trees which grow on the platform of the Harâm above us.) It has unfortunately not yet been possible to investigate the space between the double and triple gates, but it is highly probable that there are substructions here also.

We now again ascend to the plateau of the Harâm, and proceed towards the N. — The Wall which bounds the precincts of the Harâm on the right (E. side) is modern above the surface of the ground , though the substructions are of great antiquity. A little farther on we find a stair ascending to the top of the wall, which affords an admirable view of the valley of Jehoshaphat with its tombs immediately below, and of the Mt. of Olives. We And here the stump of a column built in horizontally aud protruding beyond the wall on both sides. A small building (a place of prayer) has been erected over the inner end. The Muslims say that all men will assemble in the valley of Jehoshaphat when the trumpet-blast proclaims the last judgment. From this prostrate column a thin wire-rope will then be stretched to the opposite Mt. of Olives. Christ will sit on the wall, and Mohammed on the mount, as judges. All men must pass over the intervening space on the rope. The righteous, preserved by their angels from falling, will cross with lightning speed, while the wicked will be preoipitated into the abyss of hell. The idea of a bridge of this kind occurs in the ancient Persian religion.

The Golden Gate is situated farther to the N.

A passage in Ezekiel (xliv. 1, 2) indicates that it was kept closed from a very early period. In the Book of the Acts (iii. 2) mention is also made of a &vQct (koala, or Beautiful Gate, which must certainly have been in the wall of the inner forecourt of the Temple, but modern tradition has localised it here, probably because this was the only gate still visible on the E. side of the Temple. Owing to a misunderstanding, the Greek thqala ('beautiful) was afterwards translated into the Latin aurea, whence the name 'golden gate'. Antonius Martyr, however, still distinguishes between the 'portes pre'cieuses' and the Golden Gate. The gate in its present form dates from the 5th, or probably rather from the 7th century after Christ. (According to Muslim legend the pillars of the gate were a present from the Queen of Sheba to Solomon). In the outer wall on the S. there is a very small door which probably afforded an entrance to foot-passengers. The golden gate bears a strong resemblance to the double gate on the S. side (p. 51), and probably stands nearly on the site of the gate 'Shushan' of Herod's Temple, mentioned in the Talmud. It is on record that as late as the year 629 Heraclius entered the Temple by this gate, and down to 810 a path ascended in steps from the valley of Kidron to the temple precincts. The Arabs afterwards built it up, and there still exists a tradition that on a Friday some Christian conqueror will enter by this gate and take Jerusalem from the Muslims. At the time of the Crusades the gate used to be opened for a few hours on Palm Sunday and on the festival of the Raising of the Cross. On Palm Sunday the great procession with palmbranches entered by this gate from the Mt. of Olives. The patriarch rode on an ass, while the people spread their garments in the way, as had been done on the entry of Christ.

The Arabs now call the whole gateway Bâb ed-Daherîyehy the N. arch the Bâb et-Tôbeh, or gate of repentance, and the S. arch the Bâb er-Rahmeh, or gate of mercy. The large monolithic doorposts to the E. have been converted into pillars, which now rise 6 ft, above the top of the wall, and between the two has been placed a large pillar, the sides of which are adorned with small projecting columns. Above these the arched vaulting was then placed. The gate having been walled up, the central pillar is no longer visible from without. The structure was restored in 1892, and two new buttresses were built in front of the damaged corners. A staircase ascends to the roof, which affords an excellent survey of the whole of the Temple plateau. Admission to the interior is now forbidden.

In the interior of the portal there is an arcade with six vaults, the depressed arches of which rest on one side on a frieze above the pilasters of the lateral walls, and on the other side on two columns in the middle. The inside of the W. entrance is a simple repetition pf these arrange ments of the E. gateway. The architectural details of the structure, which is highly ornate, seem to point to a Byzantine origin. The depressed vaulting, the lowness of the cornices, the hollowed form of the foliage, and the flat folding of the acanthus leaves on the capitals are all characteristic of a late period of art; and the same may be said of the capitals of the central columns with their volutes in imitation of the Ionic style, as capitals of this description do not occur before the 6th century. The hollows below the mouldings of the bases of the capitals also point to a late period. — The interior is lighted by openings in the drums of the E. domes.

Proceeding farther towards the N., we observe a modern mosque on the right, probably built over old vaults (no admission). It is called the Throne of Solomon, from the legend that Solomon was found dead here. In order to conceal his death from the demons, he supported himself on his seat with his staff, and it was not till the worms had gnawed the staff through and caused the body to fall that the demons became aware that they were released from the king's authority. Here, as at other pilgrimage shrines, we observe shreds of rags suspended from the window gratings , having been torn from the garments of the pilgrims and placed there by them in fulfilment of vows to the saint.

In this part of the Harâm, at the N. E. corner of the upper platform, subterranean arcades, probably of the Herodian period, have been discovered (no admission). This is a proof that at this point also a level area was artificially obtained by substructures, although at various other points round the platform the natural rock is exposed to view.

At the N. E. angle of the Harâm are preserved the ruins of a massive ancient tower. The N. wall contains a whole series of gates. The first at the E. end is the Bâb el-Asbât, or gate of the tribes. (The word asbât, 'tribes', has, however, sometimes been regarded as the name of some individual prophet.) The visitor should not omit to look out of one of the windows under the arcades of the N. wall, for here, far below us, lies the Birket Isra'in ('pool of Israel'), formerly regarded as the Pool of Bethesda (comp. p. 76). Early pilgrims call it the 'Sheep Pool' (Piscina Probatica), as it was erroneously supposed that the 'Sheep Gate' (St. John v. 2) stood on the site of the present gate of St. Stephen. A small valley diverged anciently from the upper part of the Tyropœon from N.W. to S.E., and was made available for the construction of this reservoir. The pool, which rarely now contains water, is 121 yds. long and 42 yds. wide. It lies 68 ft. below the level of the Temple plateau, and its bottom is now covered with rubbish to a depth of 20 ft. It was fed from the W. , and could be regulated and emptied by a channel in a tower at the S. E. corner. Near the S.W. end of the pool Capt. Warren succeeded in descending into a cistern, where he found a double set of vaulted substructions, one over the other, and to the N. of these an apartment with an opening in the N. side of the wall of the Harâm. Through this opening the superfluous water flowed away.

Skirting the N. side of the Harâm precincts, we observe places of prayer on our left, and we soon reach the next gate, called the Bâb Hitta, or Bâb Hotta, following which is the Bâb el-'Atem, or gate of darkness, also named Sherif el-Anbid (honour of the prophets) , or Gate of Dewadâr, from a school of that name situated there. This perhaps answers to the Todi gate of the Talmud. To the left is a fountain fed by Solomon's pools; near it to the W. are two small mosques, the W. one of which is called Kubbel Shektfes- Sakhra, from the piece of rock which, it is said, Nebuchadnezzar broke off from the Sakhra and the Jews brought back again. At the N.W. angle of the Temple area the ground consists of rook, in which has been formed a perpendicular cutting 23 ft. in depth, and above this rises the wall. The foundations of this wall appear to be ancient, and they may possibly have belonged to the fortress of Antonia (p. 27). There are now barracks here (PI. 11). At the N.W. corner rises the highest minaret of the Harâm.

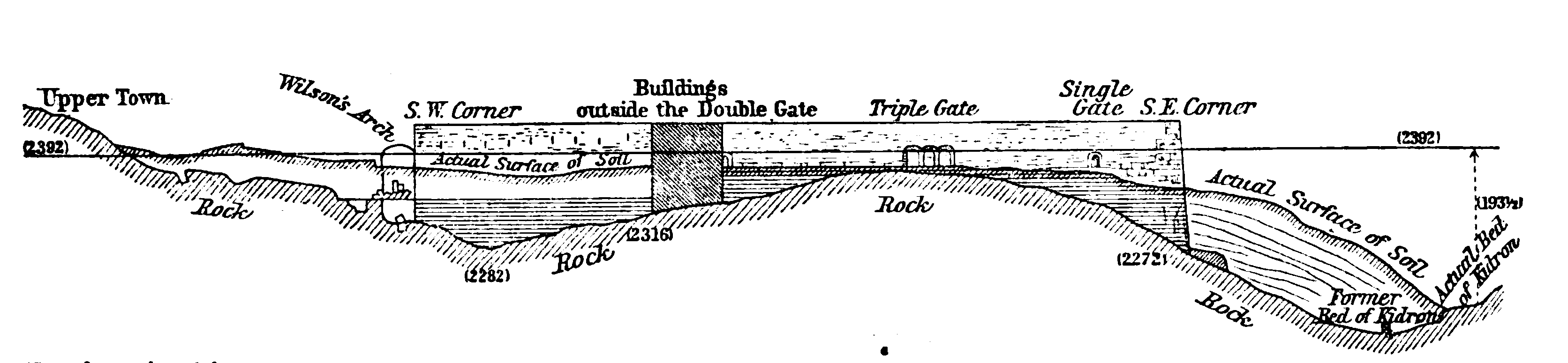

Having examined the whole of the interior of these spacious precincts, we now proceed to take a walk round the Walls of the Harâm, which will enable us better to realise the character of the substructions. What we have hitherto spoken of as a level plateau was originally a rocky hill, the sides of which were afterwards artificially raised, and the projecting parts of which at the N. W. angle were removed. Through the centre of the plateau runs the natural rock, extending below the triple gate (p. 51). The valley to the W. of it, called the Tyropœon, is almost entirely filled with rubbish.

As to the materials of which the outer wall consists, four different kinds of stones may be distinguished: — (1) Drafted blocks with rough , unhewn exterior (comp. p. cxii) ; (2) drafted blocks with smooth exterior; (3) stones, smoothly hewn, but undrafted ; (4) ordinary masonry of irregularly shaped stones. The last is modern; the third variety may be referred to the time of Justinian with tolerable certainty; while the first two are in all probability Herodian. Blocks of the first kind are to be found under ground beginning 35-55 ft. below the present surface of the ground. They are jointed without mortar or cement, but so accurately that a knife cannot be introduced between them. The wall is not perpendioular, but batters from the base, each block lying a little within that below it. On the N.W. side of the temple area (but difficult of access) the exterior of the wall shows remains of buttresses (like the temple wall in Hebron, p. 136).

On leaving the Harâm by the second gate on the N.W. side (Bâb en-Nâzir) we leave the Old Serái (at present a state-prison, PI. 95) to the right, and the cavalry-banacks to the left. At the corner to the right is a handsome fountain. (Crossing the street, we may notice how beautifully the stones of the 2nd house on the left are jointed with lead cramps.) We then turn to the left by the street which leads to the S., passing on the right the present Serâi, on the site of the former Hospital of St. Helena (PI. 94), and on the left a lane which leads to the Harâm. We now arrive at the covered-in Sûk el-Kattânin, or cotton-merchants' bazaar, now deserted, and terminating towards the E.in the Bâb el-Kattânîn, which is worthy of inspection. Ahout half-way through the bazaar we turn to the right by a by-road to the Hammâm esh-Shifû, or healing bath (PI. 35). This too has been supposed to be the Pool of Bethesda. A stair ascends 34 ft. to the mouth of the cistern, over which stands a small tower. The shaft is here about 100 ft. in depth (i. e. about 66 ft. below the surface of the earth). The basin is almost entirely enclosed by masonry; at the S. end of its W. wall runs a channel built of masonry, 100 ft. long, 3!/2 ft. high, and 3 ft. in width, first to the S., then to the S.W. The water is bad, being rain-water which has percolated through impure earth, but it is still extolled for its sanatory properties.

Returning to the narrow lane we pursue our way to the S. ; here w« find a fountain similar to the one already mentioned. We then ascend into the so-called David Street ( Tarîk Bâb es-Silseleh), which runs from W. to E. on a kind of embankment formed of subterranean arches. In Jewish times a street led over the deep valley here (the Tyropœon, p. 22) to the upper city ; one of the large arches on which it rests is named ' Wilson's Arch' after the director of the English survey. This well-preserved arch is 21 ft. in height and has a span of 42 ft. , but is now buried out of sight. Below it is the El-Burâk Pool, named after the winged steed of Mohammed, which has given its name to the whole of this W. side of the Harâm, as the prophet is said to have tied it up here. Whilst making excavations under the S. end of Wilson's Arch, Capt. Warren discovered fragments of vaulting at a depth of 24 ft. and a water-course at a depth of 42 ft. (a proof that water still trickles through what was formerly a valley) ; and at length, at a depth of more than 51 ft., he found the wall of the Temple built into the rock. A subterranean passage ran in the same direction as the viaduct over the arches mentioned above, and led from the Temple precincts to the citadel. Capt. Warren penetrated into it for a distance of ahout 83 yds., without reaching the end.

We now follow the Tarîk Bâb es-Silseleh in the direction of the Harâm until we come to another handsome fountain on the left ; here we turn to the right into the so-called 'Mehkemeh' or House of Judgment (PI. 84), a cruciform arcade with pointed vaulting, which was built in 1483. At the S. end is a prayer-recess. In the centre is a fountain which was formerly fed by the water-conduit of Bethlehem. One window looks towards the Moghrebin quarter to the S. , and another towards the plateau of the Harâm. The house of the Kâdi (judge) adjoins the arcade. The gate which here leads into the Harâm is called Bâb es-Silseleh, or Gate of the Chain ; near it is a basin which resembles a font. The great conduit from Solomon's pools (p. 129) to the area of the temple runs under the gate.

We must now return (from E. to W.) to the first narrow lane leading to the left (S.) between two handsome old houses. That on the right with the stalactite portal was a boys' school at the period of the Crusades ; that to the left, called El-'Ajemîyeh, was a girls' school, but has been used as a boys' school since the time of Saladin. Descending this lane for 4 min. and keeping to the left, we reach the "Wailing Place of the Jews (Kauthal ma'arbê), situated beyond the miserable dwellings of the Moghrebins (Muslims from the N.W. of Africa). The celebrated wall which bears this name is 52 yds. in length and 56 ft. in height. The nine lowest courses of stone consist of huge blocks, only some of which, however, are drafted. Above these are fifteen courses of smaller stones. Some of the blocks, many of which have suffered much from exposure, are of vast size, one in the N. part being 16 ft., and one in the S. part 13 ft. in length. It is probable that the Jews as early as the middle ages were in the habit of repairing hither to bewail the downfall of Jerusalem. This spot should be visited repeatedly, especially on a Friday after 4 p.m., or on Jewish festivals, when a touching scene is presented by the figures leaning against the weather-beaten wall, kissing the stones, and weeping. The men often sit here for hours, reading their well-thumbed Hebrew prayer-books. Many of them are barefooted. The Spanish Jews, whose appearance and bearing are often refined and independent, present a pleasing contrast to their squalid brethren of Poland.

On Friday, towards evening, the following litany is chanted: —

Leader: For the palace that lies desolate: — Response: We sit in solir lude and mourn.

L. For the palace that is destroyed:—R. We sit, etc.

L. For the walls that are overthrown:—R. We sit, etc.

L. For our majesty that is departed:—R. We sit, etc.

L. For our great men who lie dead:—R. We sit, etc.

L. For the precious stones that are burned:—R. We sit, etc.

L. For the priests who have stumbled:—R. We sit, etc.

L. For our kings who have despised Him:—R. We sit, etc.

Another antiphon is as follows:—

Leader: We pray Thee, have mercy on Zion! — Response: Gather the children of Jerusalem.

L. Haste, haste. Redeemer of Zion!—R. Speak to the heart of Jerusalem.

L. May beauty and majesty surround Zion!—R. Ah! turn Thyself mercifully to Jerusalem.

L. May the kingdom soon return to Zion!—R. Comfort those who mourn over Jerusalem.

L. May peace and joy abide with Zion!—R. And the branch (of Jesse) spring up at Jerusalem.

To the S. of the Place of Wailing is an ancient gate, called the Gate of the Prophet , or after the discoverer Barclay's Gate. The fanaticism of the Moghrebins prevents travellers from seeing this unless accompanied by a guide who knows the people. (For the approach from the interior of the Harâm, see p. 50.) The upper part of it consists of a huge carefully hewn block, 7 1/2 ft. thick and over 18 ft. long, now situated 10 ft. above the present level of the ground. The most interesting features of the gate, however, are not visible.

The threshold lies 48 ft. below the present surface of the ground , and a path cut in steps has been discovered in the course of excavations.

Retracing our steps from the Place of Wailing, and now turning not to the right but to the left through the main street of the dirty Moghrebin quarter till the houses cease, we reach a large open space, partly planted with cactus hedges. To the right is a precipitous slope, consisting of rubbish on the S. side and rock on the N.; to the left rises the Temple wall to a height of about 58 ft., which we now again approach not far from the S.W. angle. The colossal blocks here, one of which is 26 ft. long and 2 1/2 ft. high, and that at the corner 27 1/2 ft. long, are very remarkable, although it is some times difficult to distinguish the joints from clefts caused by disintegration. The whole S.W. corner was built during the Herodian period. About 13 yds. from the S.W. comer we come upon the arch of a bridge, called Robinson's Arch after its discoverer. The arch is 50 ft. in width; it contains stones of 19 and 26 ft. in length, and about three different courses are distinguishable. At a distance of 13 1/2 yds. to the W. Capt. Warren found the corresponding pier of the arch ; and about 42 ft. below the present surface there was a pavement upon which lie the vault-stones of Robinson's arch. This pavement farther rests upon a layer of rubbish 22 ft. in depth. Beneath the pavement the explorers discovered the vaulting-stones of a still earlier arch than Robinson's, and near the Temple-wall a conduit running N. and S. The general opinion is that Robinson's Arch is the beginning of a viaduct which led from the Temple over the Tyropœon to the Xystus, but excavations on the W. side have not yet brought to light a corresponding part of the bridge there but only a series of pillars of a different kind. Schick has therefore suggested that the bridge was of wood (Beit el-Makdas, pp. 123 f.), while others (ZDPV. xv. 234 f.) suggest that the bridge spanned the valley near Wilson's Arch (p. 65) and that Robinson's Arch is the 'staircase gate' mentioned by Josephus (Ant. xv. 11, 5) as the entrance to the 'royal portico'.

Turning round the S.W. corner of the Harâm, we can at first see only the piece to the E. as far as the 'Double Gate' (see p. 50) ; the continuation of the S. wall we cannot pursue until we issue from the Dung Gate (or Moghrebine' Gate), and turn to the E., keeping as close as possible to the wall. The rock here rapidly falls from the S.W. corner of the area towards the E. from a depth of 58 ft. to 88 ft., and then rises again towards the E. In other words — the Tyropoeon valley runs under the S.W. angle of the Temple plateau, so that this part of the mosque (corresponding to part of the ancient Temple) stands not on the Temple hill itself, but on the opposite slope.

At the bottom of this depression, which is now no longer visible, Capt. Warren discovered a subterranean channel. At a depth of 23 ft. is a stone pavement, probably of a late Roman period, and at a depth of 43 ft. another, of earlier date. A wall still more deeply imbedded in the earth consists of large stones with rough surfaces. The rock ascends to the Triple Gate, where it lies but few feet below the present surface. Thence to the S.E. corner the wall sinks again for a depth of 100 ft., while the present surface of the ground descends only 23 ft. Under the 'Triple Gate' several passages and water-conduits hewn in the rock, and under the 'Single Gate' (p. 51), which is of late date, an old passage, have been discovered. At the bottom Capt. Warren discovered a pitcher, besides masons' marks on the stones. The gigantic blocks above the surface of the ground in this S.E. angle attract our attention. Some of these are 16-22 ft. in length and 3 ft. in thickness. The wall at the S.E. corner is altogether 74 ft. in height. — In the course of his excavations towards the S., Capt. Warren discovered a second wall at a great depth, running from the S.E. corner towards the S.W., and surrounding Ophel.

On the E. side of the wall of the Harâm lies much rubbish, and the rock once dipped much more rapidly to the Kidron valley than the present surface of the ground does. The Golden Gate (p. 52) stands with its outside upon the wall, but with its inside apparently upon rock. The wall here extends to a depth of 28-38 ft. below the surface. Outside of the Harâm wall Capt. Warren discovered a second wall, possibly an ancient city-wall, buried in the debris. The whole of the N.E. corner of the Temple plateau, both within and without the enclosing wall, is filled with immense deposits of debris, some of which was probably the earth removed in levelling the N.W. corner. The small valley used for the construction of the Birket Isra'in (p. 63) runs (like the Tyropœon at the S.W. angle) under the N.E. comer of the wall, which extends here to a depth of 110 ft. below the present surface. The gradient of the rock from the N.W. corner of the Harâm to this point is therefore very rapid, and vast quantities of material were required to fill it up. — Capt. Warren also discovered the outlet of the Birket Isra'in under ground, and in the N.E. corner the ruins of a large tower, obviously ancient.

The beautiful arches of the Golden Gate should be once more viewed from without. The parts belonging to different periods may easily be distinguished. Along the whole wall are placed Muslim tombstones. The best way to return to the town is now by the Gate of St. Stephen (p. 75).