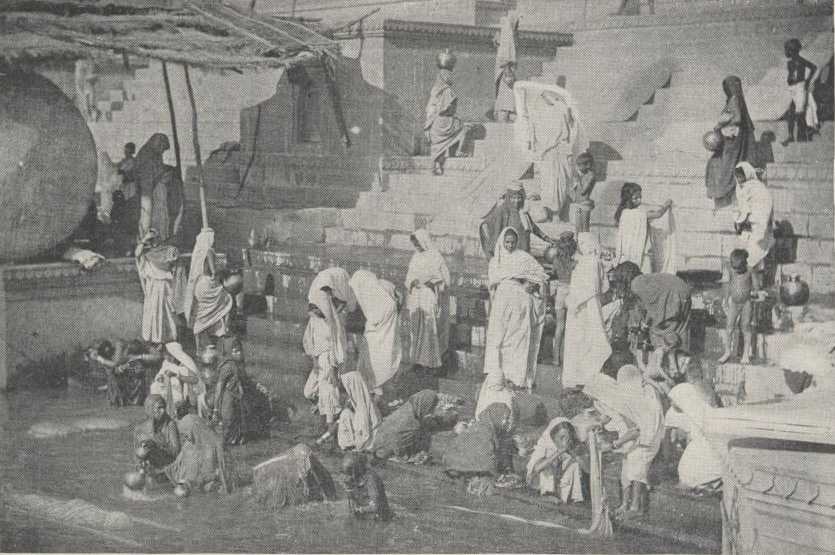

We made the usual trip up and down the river, seated in chairs under an awning on the deck of the usual commodious hand-propelled ark; made it two or three times, and could have made it with increasing interest and enjoyment many times more; for, of course, the palaces and temples would grow more and more beautiful every time one saw them, for that happens with all such things; also, I think one would not get tired of the bathers, nor their costumes, nor of their ingenuities in getting out of them and into them again without exposing too much bronze, nor of their devotional gesticulations and absorbed bead-tellings.

But I should get tired of seeing them wash their mouths with that dreadful water and drink it. In fact, I did get tired of it, and very early, too. At one place where we halted for a while, the foul gush from a sewer was making the water turbid and murky all around, and there was a random corpse slopping around in it that had floated down from up country. Ten steps below that place stood a crowd of men, women, and comely young maidens waist deep in the water-and they were scooping it up in their hands and drinking it. Faith can certainly do wonders, and this is an instance of it. Those people were not drinking that fearful stuff to assuage thirst, but in order to purify their souls and the interior of their bodies. According to their creed, the Ganges water makes everything pure that it touches—instantly and utterly pure. The sewer water was not an offence to them, the corpse did not revolt them; the sacred water had touched both, and both were now snow-pure, and could defile no one. The memory of that sight will always stay by me; but not by request.

A word further concerning the nasty but all-purifying Ganges water. When we went to Agra, by and by, we happened there just in time to be in at the birth of a marvel—a memorable scientific discovery—the discovery that in certain ways the foul and derided Ganges water is the most puissant purifier in the world! This curious fact, as I have said, had just been added to the treasury of modern science. It had long been noted as a strange thing that while Benares is often afflicted with the cholera she does not spread it beyond her borders. This could not be accounted for. Mr. Henkin, the scientist in the employ of the government of Agra, concluded to examine the water. He went to Benares and made his tests. He got water at the mouths of the sewers where they empty into the river at the bathing ghats; a cubic centimetre of it contained millions of germs; at the end of six hours they were all dead. He caught a floating corpse, towed it to the shore, and from beside it he dipped up water that was swarming with cholera germs; at the end of six hours they were all dead. He added swarm after swarm of cholera germs to this water; within the six hours they always died, to the last sample. Repeatedly, he took pure well water which was barren of animal life, and put into it a few cholera germs; they always began to propagate at once, and always within six hours they swarmed—and were numberable by millions upon millions.

For ages and ages the Hindoos have had absolute faith that the water of the Ganges was absolutely pure, could not be defiled by any contact whatsoever, and infallibly made pure and clean whatsoever thing touched it. They still believe it, and that is why they bathe in it and drink it, caring nothing for its seeming filthiness and the floating corpses. The Hindoos have been laughed at, these many generations, but the laughter will need to modify itself a little from now on. How did they find out the water's secret in those ancient ages? Had they germ-scientists then? We do not know. We only know that they had a civilization long before we emerged from savagery.