Mark Twain’s party arrived at Ceylon’s (now Sri Lanka’s) capital, Colombo, January 13, 1896. He stayed there one night before taking a six day cruise, aboard the Rosetta, to Bombay (now Mumbai), India.

Robert Cooper, in “Around the World with Mark Twain” mentions that in a letter to Henry Huttleston Rogers, Twain complains “that the toll of carbuncles and colds had left him ‘tired and disgusted and angry’.” So much so that he was unable to give an At Home that first day in Colombo, and his ship departed too early the next day for any public speaking then as well.

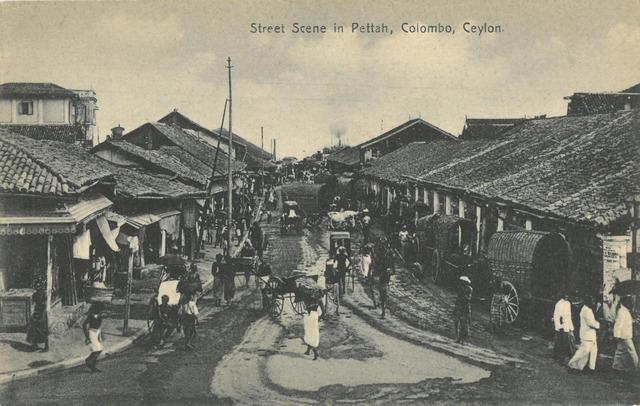

From “Following the Equator”: “… Ceylon present. Dear me, it is beautiful! And most sumptuously tropical, as to character of foliage and opulence of it. ‘What though the spicy breezes blow soft o'er Ceylon's isle’—an eloquent line, an incomparable line; it says little, but conveys whole libraries of sentiment, and Oriental charm and mystery, and tropic deliciousness—a line that quivers and tingles with a thousand unexpressed and inexpressible things, things that haunt one and find no articulate voice . . . . Colombo, the capital. An Oriental town, most manifestly; and fascinating.”

On the ship, Twain was interviewed by a reporter from the Overland Times of Ceylon (Colombo), 14 January 1896: “...he dropped up to the ship’s rail and there began to take a great interest in the diving boys and the native craft. The catamarans of the former interested him at first, but it was the outriggers that finally engrossed his attention. ‘Those boats there are just the queerest things in the way of boats that I ever saw,’ he drawled. ‘I should say that the man who first designed them was real clever. A man who could build a boat like that could build a three-story house, it seems to me, if he only made the outrigger long enough. It’s all very interesting, and so are the natives. You only see things like this is places like Fiji and places of that sort, and even there they are different. Those boats and those dresses of the natives are quite novelties. In most places you see them following European customs and ways in the matter of dress, and customes of that sort, but I should class the dresses here, and those boats as original.’ As he turned at last to leave for shore he said: ‘I must say I’m sorry to leave that scene. I never saw anything like that anywhere.’ Just then he was met by Pilot Henderson and the old Mississippi steerer shook hands cordially with him on learning his calling, his handshake being heartily returned by the local pilot.” (Gary Scharnhorst, “Mark Twain, The Complete Interviews” n 104, p268-9)

Twain’s party was unable to find accommodations at the Grand Oriental Hotel but after some searching, rooms were found at the Bristol Hotel. “Hotel Bristol. Servant Brompy. Alert, gentle, smiling, winning young brown creature as ever was. Beautiful shining black hair combed back like a woman's, and knotted at the back of his head—tortoise-shell comb in it, sign that he is a Singhalese; slender, shapely form; jacket; under it is a beltless and flowing white cotton gown—from neck straight to heel; he and his outfit quite unmasculine. It was an embarrassment to undress before him.”

“Ceylon was Oriental in the last measure of completeness—utterly Oriental; also utterly tropical; and indeed to one's unreasoning spiritual sense the two things belong together. All the requisites were present. The costumes were right; the black and brown exposures, unconscious of immodesty, were right; the juggler was there, with his basket, his snakes, his mongoose, and his arrangements for growing a tree from seed to foliage and ripe fruitage before one's eyes; in sight were plants and flowers familiar to one on books but in no other way—celebrated, desirable, strange, but in production restricted to the hot belt of the equator; and out a little way in the country were the proper deadly snakes, and fierce beasts of prey, and the wild elephant and the monkey. And there was that swoon in the air which one associates with the tropics, and that smother of heat, heavy with odors of unknown flowers, and that sudden invasion of purple gloom fissured with lightnings,—then the tumult of crashing thunder and the downpour and presently all sunny and smiling again; all these things were there; the conditions were complete, nothing was lacking. And away off in the deeps of the jungle and in the remotenesses of the mountains were the ruined cities and mouldering temples, mysterious relics of the pomps of a forgotten time and a vanished race—and this was as it should be, also, for nothing is quite satisfyingly Oriental that lacks the somber and impressive qualities of mystery and antiquity.”

“The drive through the town and out to the Galle Face by the seashore, what a dream it was of tropical splendors of bloom and blossom, and Oriental conflagrations of costume! The walking groups of men, women, boys, girls, babies—each individual was a flame, each group a house afire for color. And such stunning colors, such intensely vivid colors, such rich and exquisite minglings and fusings of rainbows and lightnings! And all harmonious, all in perfect taste; never a discordant note; never a color on any person swearing at another color on him or failing to harmonize faultlessly with the colors of any group the wearer might join. The stuffs were silk—thin, soft, delicate, clinging; and, as a rule, each piece a solid color: a splendid green, a splendid blue, a splendid yellow, a splendid purple, a splendid ruby, deep, and rich with smouldering fires—they swept continuously by in crowds and legions and multitudes, glowing, flashing, burning, radiant; and every five seconds came a burst of blinding red that made a body catch his breath, and filled his heart with joy. And then, the unimaginable grace of those costumes! Sometimes a woman's whole dress was but a scarf wound about her person and her head, sometimes a man's was but a turban and a careless rag or two—in both cases generous areas of polished dark skin showing—but always the arrangement compelled the homage of the eye and made the heart sing for gladness.

I can see it to this day, that radiant panorama, that wilderness of rich color, that incomparable dissolving-view of harmonious tints, and lithe half-covered forms, and beautiful brown faces, and gracious and graceful gestures and attitudes and movements, free, unstudied, barren of stiffness and restraint, and—“

“Just then, into this dream of fairyland and paradise a grating dissonance was injected.” “Out of a missionary school came marching, two and two, sixteen prim and pious little Christian black girls, Europeanly clothed—dressed, to the last detail, as they would have been dressed on a summer Sunday in an English or American village. Those clothes—oh, they were unspeakably ugly! Ugly, barbarous, destitute of taste, destitute of grace, repulsive as a shroud. I looked at my womenfolk's clothes—just full-grown duplicates of the outrages disguising those poor little abused creatures—and was ashamed to be seen in the street with them. Then I looked at my own clothes, and was ashamed to be seen in the street with myself.”

Twain’s ship was departing too early to allow for any public speaking, but Twain was taken on a tour of Colombo, the first place he was shown, much to his disgust (Cooper) was the new post office. Cooper mentions that Twain told a reporter in Bombay that his day in Colombo was “the most enchanting day I ever spent in my life...” After spending two months in India, Twain returned to Colombo for several days and delivered two public lectures before heading for Mauritius. He makes no note of this visit in “Following the Equator” other than to mention that his party spent two or three days in Ceylon while on their way. Robert Cooper provides an addendum to Twain’s narrative on Ceylon: today "..., schoolchildren universally wear the 'ugly, barbarous' clothes of the West. As for adults, the semi-nakedness and whirl of vivid color that intoxicated Clemens has been largely replaced, for the workaday world, by conventional Western dress. Colombo is still colorful, but its tints and hues derive mainly from tropical flowers and the aquamarine sea." (p 185).