Samuel L. Clemens was born in the small village of Florida but the family soon moved to the town of Hannibal, Missouri. After a Tom Sawyer childhood, at the age of seventeen Sam set out to see the world supporting himself as a restless journeyman printer.

Possibly the best sources for learning about Twain's Hannibal Years are "The Adventures of Tom Sawyer" and "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn". For an analysis of this time see "Huck Finn's America", subtitled "Mark Twain and the Era that shaped his Masterpiece" by Andrew Levy.

A perspective on American History 1821 to 1853.

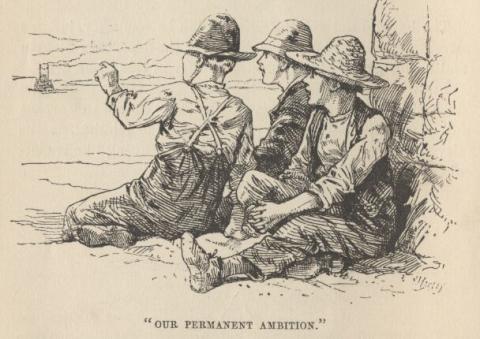

Sam never truly left Hannibal—he carried it in his heart and memory and poured it out into The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Hannibal in those pages would become a universal boyhood home, an icon like the man himself. Sam would visit again in 1882 to gather material for Life on the Mississippi, and the last time in 1902. In many ways Sam Clemens would always be the boy of Hannibal—his wife Livy would call him “youth.”

One aspect of Sam Clemens' youth that intruded itself into his and his brother, Orion's life, was his fathers purchase of "The Tennessee Land". John Marshall Clemens may have acquired a tract as large as forty thousand acres in a single transaction, but he also bought numerous smaller parcels, beginning as early as 1826 and continuing until at least 1841. In 1857, ten years after his death, the family had ownership records for twenty-four tracts of unknown acreage. After surveying the land in 1858, Orion concluded that he could establish title to some 30,000 acres, less than half of the 75,000 acres that Clemens estimates here. "[The Tennessee Land in Autobiography of Mark Twain, Volume 1. 2010