East of Napoleon, The Beulah Bend (now Lake Beulah) was a 10-mile arc of the Mississippi River that started at the mouth of the Arkansas and semi-circled back around to within a mile of the Arkansas river's mouth.[6][7] During the American Civil War, Confederate soldiers would move east by foot from Napoleon, hide in a wooded area near the bend, and then fire on passing Union ships. The bend was so tight that Rebels could fire at a ships headed down stream the Mississippi and leisurely move cannons a few hundred yards to wait and fire at the same ships.

Selfridge sought to dig a canal that would reroute the river from the Beulah bend. He obtained the idea when he noticed the floodwaters near Beulah Bend made the distance feasible. The tactic (Grant's Canal) had failed miserably at the Siege of Vicksburg but Selfridge put his men to work on digging a canal only a few hundred yards long. It didn't take long. In just a single day the water had made a raging torrent cut into the earth and carried even large trees. The next morning Selfridge couldn't wait. He opened up the new canal at full speed in the Conestonga, estimating the current to be at 12 knots and surprised transport ship that had seen them behind them the day prior.

Though the cut had improved river traffic, the cut hastened the end of Napoleon. The Mississippi's water was soon eroding the banks of the town. Ten years after the canal was dug the town would be gone. Napoleon after the war was practically a ghost town.

Although several families returned, most didn't. A Newspaper in Napoleon (The Napoleon News) came back and 1870 and claimed that silver had been discovered near the town.

Many were hopeful for the town to return to prosperity but Napoleon would not become the host of a silver boom nor much else. Floods continued. The Mississippi cut into the town separating one side from the other. Thieves were creative and used a flat boat to steal the safe from the county clerk's office. While the safe had no money, it contained town records.

The Catholic Church bell is now at McGehee. All that is left of Napoleon are a few ruins which are only visible when the water is low.

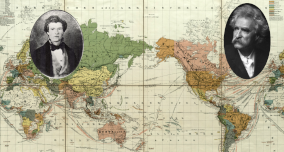

Mark Twain tells a long story of why he has an errand to run in Napoleon, unaware that it no longer existed.

This matter warmed up into a quarrel; then into a fight; and each man got pretty badly battered. As soon as I had got myself mended up after a fashion, I ascended to the hurricane deck in a pretty sour humor. I found Captain McCord there, and said, as pleasantly as my humor would permit—

'I have come to say good-bye, captain. I wish to go ashore at Napoleon.'

'Go ashore where?'

'Napoleon.'

The captain laughed; but seeing that I was not in a jovial mood, stopped that and said—

'But are you serious?'

'Serious? I certainly am.'

The captain glanced up at the pilot-house and said—

'He wants to get off at Napoleon!'

'Napoleon?'

'That's what he says.'

'Great Caesar's ghost!'

Uncle Mumford approached along the deck. The captain said—

'Uncle, here's a friend of yours wants to get off at Napoleon!'

'Well, by —?'

I said—

'Come, what is all this about? Can't a man go ashore at Napoleon if he wants to?'

'Why, hang it, don't you know? There isn't any Napoleon any more. Hasn't been for years and years. The Arkansas River burst through it, tore it all to rags, and emptied it into the Mississippi!'

'Carried the whole town away?-banks, churches, jails, newspaper-offices, court-house, theater, fire department, livery stable everything ?'

'Everything. just a fifteen-minute job.' or such a matter. Didn't leave hide nor hair, shred nor shingle of it, except the fag-end of a shanty and one brick chimney. This boat is paddling along right now, where the dead-center of that town used to be; yonder is the brick chimney-all that's left of Napoleon. These dense woods on the right used to be a mile back of the town. Take a look behind you—up-stream—now you begin to recognize this country, don't you?'

'Yes, I do recognize it now. It is the most wonderful thing I ever heard of; by a long shot the most wonderful—and unexpected.'

Mr. Thompson and Mr. Rogers had arrived, meantime, with satchels and umbrellas, and had silently listened to the captain's news. Thompson put a half-dollar in my hand and said softly—

'For my share of the chromo.'

Rogers followed suit.

Yes, it was an astonishing thing to see the Mississippi rolling between unpeopled shores and straight over the spot where I used to see a good big self-complacent town twenty years ago. Town that was county-seat of a great and important county; town with a big United States marine hospital; town of innumerable fights—an inquest every day; town where I had used to know the prettiest girl, and the most accomplished in the whole Mississippi Valley; town where we were handed the first printed news of the 'Pennsylvania's' mournful disaster a quarter of a century ago; a town no more—swallowed up, vanished, gone to feed the fishes; nothing left but a fragment of a shanty and a crumbling brick chimney!