See pages 151-54 The Life of Mark Twain - The Middle Years 1871-1891:

Probably from the Boston Times of 16 Nov 74:

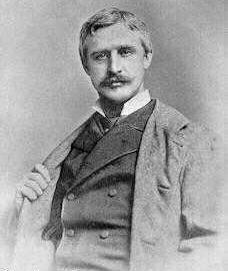

MARK TWAIN.

HIS RECENT WALKING FEAT.

He Tells a Times Reporter All About It—The Beauty of Getting Away from Railroads—What He Intends Doing Another Year.

[written for the boston times.]

As most readers of the Times are aware, Mark Twain, known to a select circle of relatives and friends as Mr. Samuel L. Clemens, recently undertook, in company with his friend and pastor, Rev. J. H. Twitchell, to achieve pedestrian fame. He started with Mr. Twitchell from Hartford at 9 A. M. on Thursday last, intending to reach Boston by way of the old turnpike road yesterday. On Friday they hitched on to a train and reached Boston at seven o’clock in the evening, ahead of the time in which they had proposed to do the journey. Feeling certain that the public would like to know from the adventurous Twain’s own lips the details of the journey, a Times reporter called on him at Young’s Hotel, last evening, and enjoyed the following conversation with him:

Reporter—Mr. Clemens, the readers of our paper would like to learn the particulars of your journey from Hartford.

Mark Twain—Certainly, sir. We originally intended to leave Hartford on Monday morning and take a week to walk to Boston, just loafing along the road, and walking, perhaps, fifteen or eighteen miles a day, just for the sake of talking and swopping experiences, and inventing fresh ones, and simply enjoying ourselves in that way, without caring whether we saw anything or found out anything on the road or not. We were to make this journey simply for the sake of talking. But then our plan was interrupted by Mr. Twitchell having to go to a Congregational Conference of Ministers at Bridgeport, so we could not start till Thursday. We thought we would simply do two days, walking along comfortably all the time, and bringing on night just where it chose to come, and about noon, Saturday, we would get a train that would take us into Boston. We got so ambitious, however, the first day, and felt so lively that we walked twenty-eight miles.

Reporter—Did you experience any fatigue at the end of that day’s work?

Twain—Well, at the end of that day when we stopped for the night I didn’t feel fatigued, and I had no desire to go to bed, but I had a pain through my left knee which interrupted my conversation with lockjaw every now and then. The next day at twelve past five we started again, intending to do forty miles that day, believing we could still make Boston in three days. But we didn’t make the forty miles. Finding it took me three or four hours to walk seven miles, as my knee was still so stiff that it was like walking on stilts—or, if you can imagine such a thing, it was as though I had wooden legs with pains in them—we just got a team and drove to the nearest railway station, hitched on, and came up here.

Reporter—You could doubtless have accomplished the journey on foot, sir?

Twain—Oh, our experience undoubtedly demonstrates the possibility of walking. By and by, when we get an entire week to make this pedestrian excursion, we mean to make it.

Reporter—When you renew the experiment, do you intend to follow any different plan?

Twain—No, I would just follow the old Hartford and Boston stage-road of old times. It takes you through a lot of quiet, pleasant villages, away from the railroads, over a road that now has so little travel that you don’t have to be skipping out into the bushes every moment to let a wagon go by, because no wagon goes by. And then you see you can talk all you want, with nobody to listen to what you say; you can have it all to yourself, and express your opinions pretty freely.

Reporter—Were the opportunities for refreshment by the way good?

Twain—Well, I suppose pretty fair, especially if you are walking all day.

Reporter—Do you intend to lecture in Boston, now you are here?

Twain—No, not at all. I simply intend to go back home again. I shall lie over Sunday to rest, and let Mr. Twitchell have a chance to preach at Newton. You may as well say that we expect hereafter to walk up to Boston, and after we get into the habit of this sort of thing, we may extend it perhaps to New Orleans or San Francisco. Really, though, there was no intention on our part to excite anybody’s envy or make Mr. Weston feel badly, for we were not preparing for a big walk so much as for a delightful walk.

Mark was holding his napkin between his forefinger and thumb all the time, standing in the doorway of Room 9, in which a select party of his friends were impatiently awaiting his return to the table, and so our reporter abstained from asking him, as he intended and ought to have done, as to whether a bottle-holder would not be a good feature in his next trip and various other important queries. Thanking him he accordingly withdrew.