Bædeker (1898) Route 10 page 121

The large *Church of St. Mary, erected over the traditional birth place of Christ, lies in the E. part of the town, above the Wâdi el-Hrobbeh, and is the joint property of the Greeks, Latins, and Armenians.

The tradition which localises the birth of Christ in a Cavern near Bethlehem extends back as far as the 2nd century (Justinus Martyr). As an insult to the Christians, Hadrian is said to have destroyed a church which stood on the sacred spot, and to have erected a temple of Adonis on its site, but this story is not authenticated. In 330 a handsome basilica was erected here by order of the Emperor Constantine. The assertion that the present church is the original structure is based on the simplicity of its style and the absence of characteristics of the buildings of the subsequent era of Justinian. Other authorities consider it beyond question that the Church of St. Mary underwent considerable restoration in the days of Justinian (627-565). In any case, we are about to visit a church of venerable antiquity, and one which is specially interesting as an example of the earliest Christian style of architecture. In the year 1010 the church is said to have miraculously escaped destruction by the Muslims under Hâkim, and the Franks found the church uninjured.Throughout the accounts of all the pilgrims of the middle ages there prevails so remarkable an unanimity regarding the situation and architecture of the church, that there can be little doubt that it has never been altered. On Christmas Bay, 1101, Baldwin was crowned king here, and in 1110 Bethlehem was elevated to the rank of an episcopal see. The church soon afterwards underwent a thorough restoration, and the Byzantine emperor Manuel Comnenos (1143-1180) munificently caused the walls to be adorned with gilded mosaics. These were executed by an architect named Efrem, who introduced the effigy of the emperor at various places. The church was covered with lead. In 1482 the roof, which had become dilapidated, was repaired, Edward IV. of England giving the lead for the purpose, and Philip of Burgundy the pine-wood. The woodwork was executed by artificers of Venice. At that period the mosaics fell into disrepair, and the condition of the roof soon became the subject of new complaints. Towards the end of the 17th cent, the Turks stripped the roof of its lead, in order to make bullets. On the occasion of a restoration of the church in 1672 the Greeks managed to obtain possession of it. The Latins, who had long been excluded, were admitted to a share of the proprietorship of the church through the in tervention of Napoleon III. in 1852.

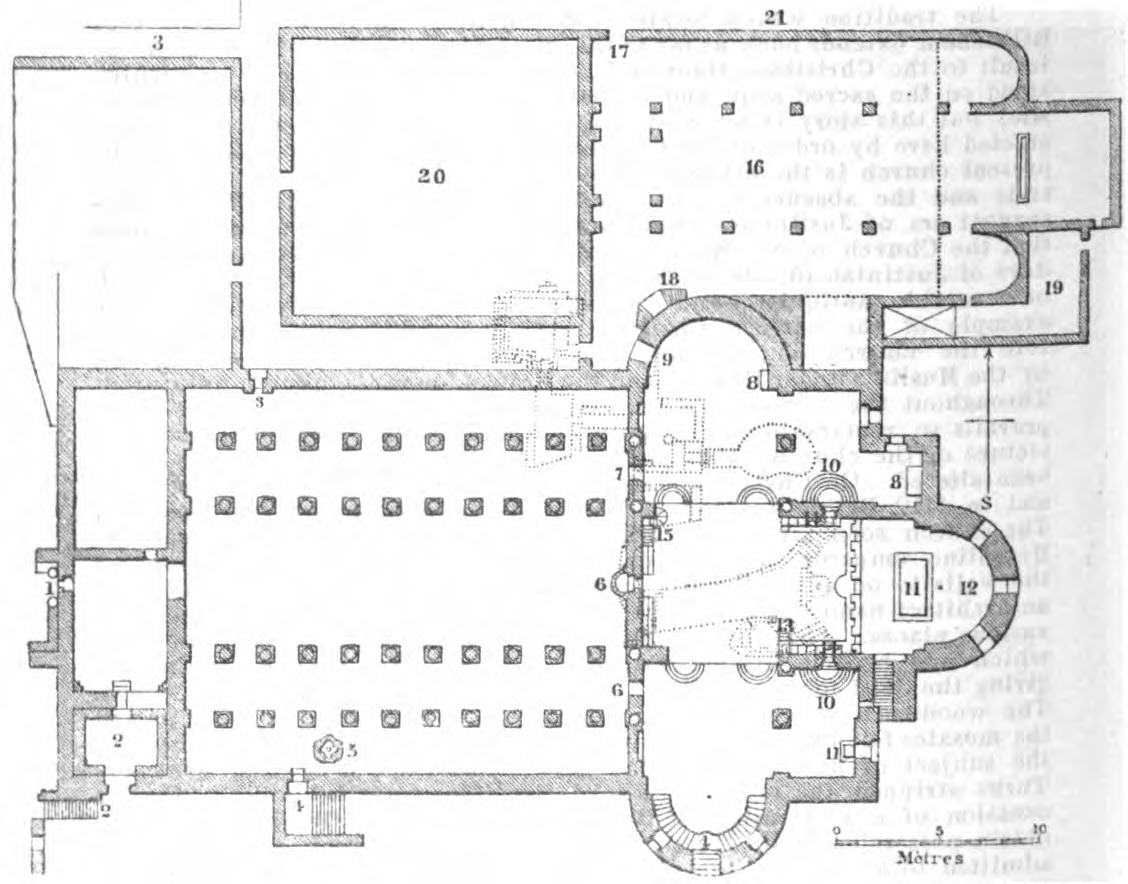

In front of the principal Entrance on the W. side (PLl) lies a large paved space, in which traces of the former atrium of the basilica have been discovered. This was a quadrangle surrounded by colonnades, in the centre of which were several cisterns for ablutions and baptisms. From the atrium three doors led into the vestibule of the church; but of these the central one only has been preserved, and it has long been reduced to very small dimensions from fear of the Muslims. The portal is of quadrangular form, and the simply decorated lintel is supported by two brackets. The windows on each side are built up. The porch is as wide as the nave of the church, but is not higher than the aisles, so that its roof is greatly overtopped by the pointed gable of the church. The porch is dark, and is divided by walls into several chambers. One door only leads from it into the church, instead of three as formerly.

- 1. Principal Entrance.

- 2. Entrance to the Armenian Monastery.

- 3. Entrance to the Latin Monastery andClmrch.

- 4. Entrances to the Greek Monastery.

- 5. Font of the Greeks.

- 6. Entrances of the Greeks to the Choir.

- 7. Common Entrance of the Greeks and Armenians to the Choir.

- 8. Armenian Altars.

- 9. Entrance to the Latin Church.

- 10. Steps leading to the Grotto of the Nativity (comp. Plan, p.124).

- 11. Greek Altar.

- 12. Greek Choir.

- 13. Throne of the Greek Patriarch.

- 14. Seats of the Greek Clergy.

- 15. Pulpit

- 16. Latin Church of St. Catharine.

- 17. Entrance to the Latin Monastery.

- 18. Stairs to the Grottoes.

- 19. Latin Sacristy.

- 20. Schools of the Franciscans.

- 21. Latin Monastery.

The dotted lines in the Plan indicate the situation of the grottoes under the church.

On entering the church we are struck by the grand simplicity of the structure, but the transept and apse are unfortunately concealed by a wall erected by the Greeks in 1842. The building consists of a nave and double aisles, the nave being wider (11 1/2yds.) than either pair of aisles ( 4'/2 yds. and 4 yds.). The floor is paved with large slabs of stone. Each pair of aisles is separated by two rows of eleven monolithic columns of reddish limestone, with white veins. The base of each column rests on a square slab. The capitals are Corinthian, but show a decline of the style; at the top of each is engraved a cross. The columns, including capitals and bases, are 19 ft. high. Above the columns are architraves. In the aisles these architraves bear the wooden beams of the roof. The aisles were not, as elsewhere, raised to the height of the nave by means of an upper gallery , but walls were erected to a height of about 32 ft. above the architraves of the inner row of columns for the support of the roof-beams of the nave. These form a pointed roof, dating from the end of the 17th cent., and once richly painted and gilded. The church is lighted only by the windows in the upper part of the wall, each window corresponding to a space between the columns. Unfortunately very little has been preserved of the mosaics of Comnenus, coloured glass cubes set in a ground of gold. This fivefold series of mosaics represented the following subjects, beginning from below: (1) A series of half-figures representing the ancestors of Christ; (2) A number of the most important Councils, with groups of fantastic foliage between them; (3) A frieze of foliage with rows of heading ; (4) Figures of angels between the windows; (5) A frieze similar to No. 3. On the S. (right) side there are now about seven busts only, which represent the immediate ancestors of Joseph; above these are arcades, containing altars concealed by curtains, on which books of the Gospels are placed. The inscription above contains an extract from the resolutions of the Council of Constantinople , and still higher are two crosses. Adjoining the arcades is placed a large, fantastic, artificial plant. On the N. (left) side, in the intervening spaces , are placed fantastic plants with vases or crosses ; but for the arcades are substituted representations of sections of churches, containing altars with books of the Gospels. Two of these are still preserved, via. The churches of Antioch and Sardike, and one-half of a third church. The drawing is very primitive, being without perspective. Here, too, are Greek inscriptions relating to the resolutions of Councils. The order in which the Councils were represented, with the relative inscriptions, is recorded in the writings of the earlier pilgrims. There are figures of six angels between the windows.

A passage from the N.or S. aisle next leads us into the Transept, which is of the same width as the nave. The four angles, formed by the intersection of the transept with the nave are formed by four large piers , into which are built half-columns corresponding to the columns of the nave. The transepts terminate in semicircular apses. The nave is prolonged beyond the transept, but the aisles here are of unequal length, terminating in a straight wall, while the nave ends in an apse like those of the transept. This part of the church also was once embellished with mosaics, chiefly representing the history of Christ. The S. apse of the transept contains a very quaint representation of the Entry into Jerusalem. Christ, accompanied by a disciple (the other figures having been destroyed), is riding on the ass. The people come from Jerusalem to meet him, and among them is observed a woman with a child sitting on her left shoulder. Children spread their garments in the way, and a man climbs a tree to cut branches. In the N. apse of the transept is a representation of the scene where Christ invites Thomas to examine his wounds. The apostles here are without the nimbus. In the background is seen a closed door, in front of which are arcades with foliaged capitals. The third fragment represents the Ascension, but the upper part is gone. Here again the apostles are without the nimbus ; in their midst is the Virgin between two angels. The other small fragments are unimportant.

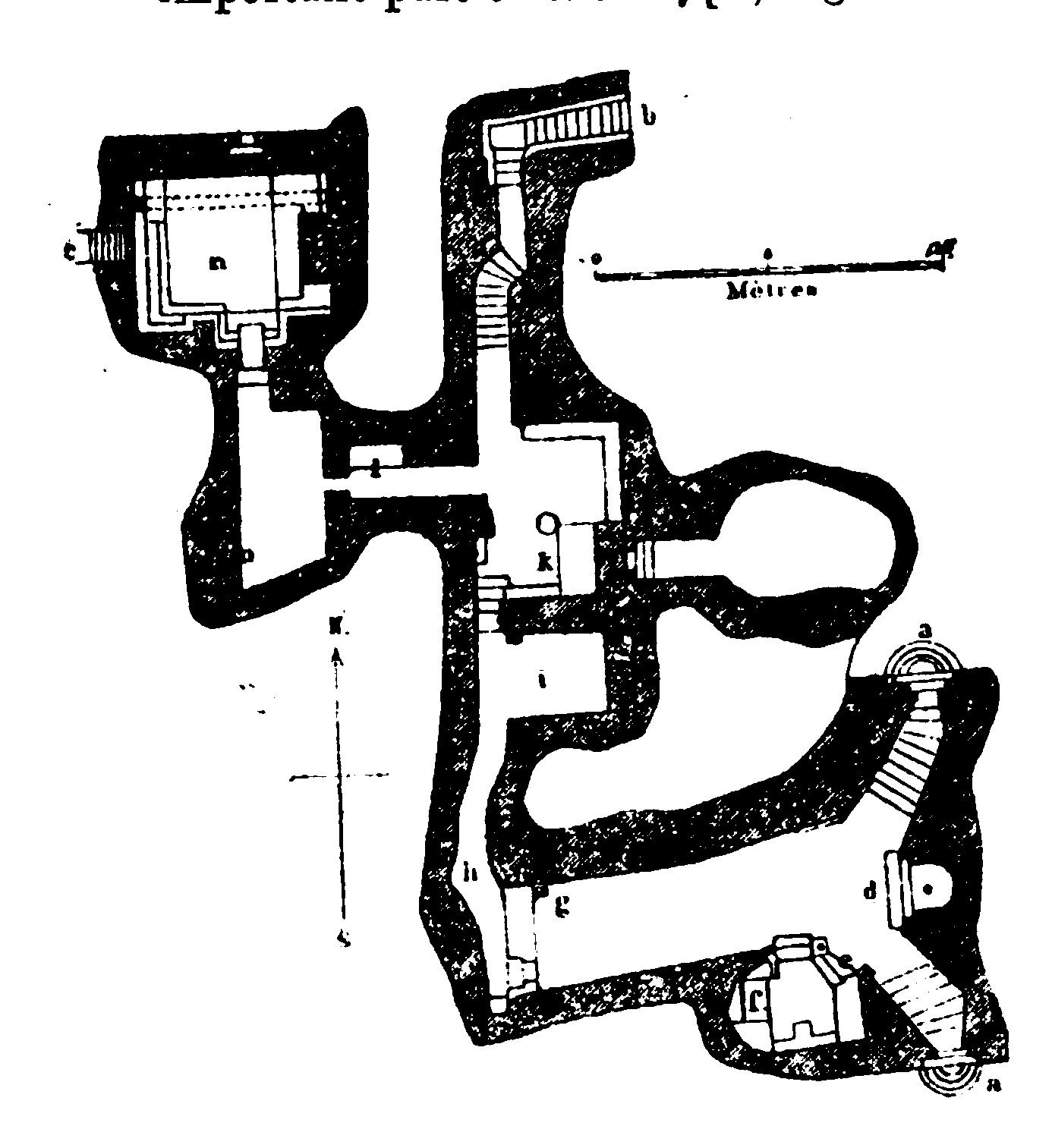

Into the Crypt:

- a. Stair to the Crypt, descending from the Greek choir of the church of St Mary (see Plan , p. 122).

- b. Stairs to the Crypt, from the Latin Church of St. Catharine.

- c. Stairs now closed,

- d. Place of the Nativity,

- e. Manger of the Latins.

- f. Altar of the Adoration of the Magi.

- g. Spring of the Holy Family,

- h. Passage in the Rock.

- i. Scene of the Vision commanding the flight into Egypt,

- k. Chapel of the Innocents.

- 1. Tomb of Eusebius.

- m. Tomb of St. Jerome,

- n. Chapel of St. Jerome.

We now descend to the Crypt, situated under the great choir. It has three entrances, two from the choir (PI. a) ; the third entrance (PI. b) is from the church of St. Catharine and was constructed in 1479 by the Minorites. The two staircases (PI. a, a) descend through doors direct into the Chapel of the Nativity, the most important part of the crypt, lighted by 32 lamps. It is 13 1/2 yds. long (from E. to W.), 4 yds. wide, and 10 ft. high. The pavement is of marble, and the walls, which are of masonry, are lined with marble. Under the altar in the recess to the E., a silver star ( PI. d") is let into the pavement, with the inscription 'Hic de Virgine Maria Jesus Christus natus est'. Around the recess burn 15 lamps, of which 6 belong to the Greeks, 5 to the Armenians, and 4 to the Latins. The recess still shows a few traces of mosaics. This sacred spot was richly decorated as early as the time of Constantine, and even with the Muslims was in high repute at a later period.

Opposite the recess of the Nativity are three steps (PI. e) descending to the Chapel of the Manger. The manger, in which, according to tradition, Christ was once laid, is of marble, the bottom being white , and the front brown ; a wax-doll represents the Infant. The finding of the 'genuine' manger, which was carried to Home, is attributed to the Empress Helena. The form of the chapel and manger of Bethlehem have in the course of centuries undergone many changes. — In the same chapel, to the E. , is the Altar of the Adoration of the Magi (PI. f), belonging to the Latins. The picture is quite modern.

We now follow the subterranean passage towards the W. At its end, we observe a round hole (PI. g) on the right, out of which water is said to have burst forth for the use of the Holy Family. In the 15th cent, the absurd tradition was invented that the star which had guided the Magi fell into this spring, in which none but virgins could see it. Passing through a door andtur ning to the right, we enter a narrow passage in the rock (PI. h), probably hewn by the Franciscans in 1476-79, leading to the chapel (PI. i; fitted up in 1621) where Joseph is said to have been commanded by the angel to flee into Egypt. Other Scriptural events were also associated by tradition with this spot. Five steps descend hence to the Chapel of the Innocents (PI. k), where, according to a tradition of the 15th cent., Herod caused several children to be slain, who had been brought here for safety by their mothers. The rocky ceiling is borne by a thick column. Under the altar is an iron gate; generally closed, leading to a small natural grotto.

Proceeding in a straight direction, we reach a stair ascending to the church of St. Catharine, where we turn to the left and come to the altar and tomb of Eusebius of Cremona (PI. 1), of which there is no mention before 1556. A presbyter named Eusebius (not to be confounded with Eusebius, Bishop of Cremona in the 7th cent.) was a pupil of St. Jerome, but that he died in Bethlehem is very unlikely. Farther on is the Tomb of St. Jerome (PI. m), hewn in the rock. The tomb of the saint has been shown for about three centuries on the W. side; opposite, on the E., the tombs of Ids pupil Paula and her daughter Eustochium (formerly on the S. side of the church) have been shown since 1566.

St. Jerome was born about 340-342. While journeying in the East he had a vision at Antioch, commanding him to renounce the study of heathen writers. He then became an ascetic , went to Constantinople, and afterwards to Rome, where he interpreted the Bible to a band of Christian women. Paula, a Roman lady, and her daughter, accompanied him thence on a pilgrimage to the holy places, after which he retired to a cell near Bethlehem, where he presided over a kind of monastery, Paula becoming head of a nunnery. He died in 420. At a very early period, it began to be related that he desired to be buried near the Place of the Nativity. St. Jerome is chiefly famous as a scholar. As a dogmatist he anxiously strove to support the orthodox doctrine of the church. He learned Hebrew from the Jews, and translated the Bible into Latin (the Vulgate). Interesting letters written by him are also still extant.

A little farther to the N. is the large Chapel of St. Jerome (PI. n), in which he is said to have dwelt and to have written his works. It was originally hewn out of the rock, but is now lined with walls. A window looks towards the cloisters. A painting here represents St. Jerome with a Bible in his hand. The chapel is mentioned for the lirst time in 1449, and the tomb of the saint was also once shown here.

Retracing our steps, we ascend the stairs (VI. b) leading to the Church of St. Catharine. Here Christ is said to have appeared to St. Catharine of Alexandria and to have predicted her martyrdom. The church is probably identical with a chapel of St. Nicholas mentioned in the 14th century. It is handsomely fitted up and in 1861 was entirely re-erected and enlarged by the Franciscans, principally at the expense of the Emperor of Austria. On the N. and W. is the Monastery of the Franciscans, which overlooks the Wâdi'el-Hrobbeh, looking like a fortress with its massive walls. Within its precincts are several fine orchards. — S. of the basilica are the Armenian and the Greek Monastery. The Emperor of Russia has built for the Greeks a pretty tower, from which we have the most beautiful view of Bethlehem and its environs, particularly towards the S. and E. , into the Wâdi er-Râhib , and towards Tekoah and the Frank Mountain.

To the S. of the basilica a street leads from the forecourt between houses, the Greek Monastery and its dependencies, back to the open air. The chain of hills still continues for some distance before we reach the descent into the valley. After 5 min. we come to the Milk Grotto, or Women's Cavern, to which 16 steps descend from a large, open, and vaulted entrance. The rocky cavern is about 5 1/2 yds. long, 3 yds. wide, and 8 ft. high. The tradition from which it derives its name, and of which there are various versions , is that the Holy Family once sought shelter or concealment here, and that a drop of the Virgin's milk fell on the floor of the grotto. For many centuries both Christians and Muslims have entertained a superstitious belief that the rock of this cavern has the property of increasing the milk of women and even of animals, and to this day round cakes mixed with dust from the rock are sold to pilgrims.