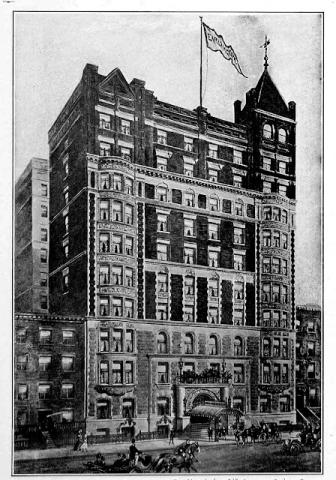

Originally known as the Hotel Gerlach:

One of the residents that year [1895?] was Yugoslavian scientist and inventor Nikola Tesla. His laboratory was located at No. 33-35 South Fifth Avenue. Here he worked on his experiments in fluorescent lighting and wireless transmission of power. The lab and the hotel were approximately 30 blocks apart—the perfect distant for experimenting with wireless transmissions.

Tesla erected his transmission equipment on the roof of the lab building downtown. With his assistant Diaz Buitrago in charge of the transmitter, Tesla set up receivers on the roof of the Hotel Gerlach. It was here that he proved that electrical energy could be received remotely.

Around 2:30 a.m. on March 13, 1895, a fire broke out on the ground level of the South Fifth Avenue building. The entire laboratory was destroyed. The New York Times lamented “The wizard and rival of Thomas A. Edison was burned out. His shop, plant, all his apparatus for conducting the scientific experiments on which the gaze of the world is riveted these days, were destroyed.”

Tesla returned to the Hotel Gerlach and closed himself in his rooms, not to be heard from for days. The scientist emerged with a greater fervor for his work. Two years later journalist Franklin Chester wrote in part “The daily life of this man has been the same, practically ever since he has been in New York. He lives in the Gerlach, a very quiet family hotel, in 27th street, between Broadway and Sixth avenue. He starts for his laboratory before 9 o’clock in the morning, all day long he lives in his weird, uncanny world, reaching forth to capture new power to gain fresh knowledge.”

...

After nearly two decades of running the hotel, Charles Gerlach stepped down. On June 22, 1899 The New York Times reported that the hotel had been leased to Warren Leland, Jr. for ten years. “It was also said that $150,000 is to be expended in general improvements to the house, which is to be opened under Mr. Leland’s management Oct. 1.”

Leland told reporters that he intended to change the name to the Knickerbocker. Instead, E. M. Earle was put in charge of the hotel and it was renamed the Hotel Earlington. From a marketing point of view, the name made sense. Earle also ran the Hotel Earlington in Richfield Springs, New York; an upscale resort hotel where millionaires spent their summers. In 1901 the hotel advertised what seems to be a bargain price for dinner. “Restaurants and Palm Room, Orchestra; Table d’Hote Dinner, One Dollar.” At the time Samuel Clemens and his wife and daughter were staying in the hotel.

Earle’s renovations brought the aging hotel up to date. Rand, McNally & Co.’s Handy Guide described the Hotel Earlington in 1901:

Practically a new house is the Hotel Earlington, in Twenty-seventh Street, near Broadway. Formerly known as the Gerlach, it was run as a family hotel, but now that it is to be used for the transient trade as well, it has been thoroughly made over, wholly remodeled on the inside, and refurnished, all at an outlay of nearly $200,000. The building itself cost $1,000,000.

Among the innovations was a system of telephones and call bells that connected every room with the office. A private electrical plant supplied power to over 3,000 electric lights. The building was heated by steam and the elevators “are large and run all night from floor to roof.”

Earle had gutted the interiors. “Only the walls and floors were retained in the reconstruction,” said the Handy Guide. There were 250 guest rooms which were arranged so they could be opened into suites of up to seven rooms each.