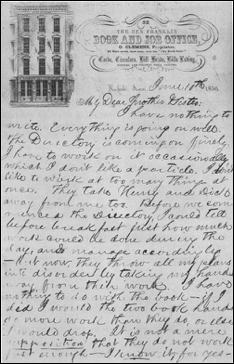

May 21 and May 25 Sunday – Sam wrote Annie Taylor a humorous letter. Sam stayed in Keokuk over a year. He enjoyed the companionship of Henry and Mollie’s circle of women friends.

[This first part written on May 21 is lost]

of the hurricane deck is still visible above the water. Here is another “Royal George” —I think I shall have to be a second Cowper, and write her requiem.

Sunday, May 25.

Well, Annie, I was not permitted to finish my letter Wednesday evening [May 21]. I believe Henry, who commenced his a day later, has beaten me. However, if my friends will let me alone I will go through today. Bugs! Yes, B-U-G-S! What of the bugs? Why, perdition take the bugs! That is all. Night before last I stood at the little press until nearly 2 o’clock, and the flaring gas light over my head attracted all the varieties of bugs which are to be found in natural history, and they all had the same praiseworthy recklessness about flying into the fire. They at first came in little social crowds of a dozen or so, but soon increased in numbers, until a religious mass meeting of several millions was assembled on the board before me, presided over by a venerable beetle, who occupied the most prominent lock of my hair as his chair of state, while innumerable lesser dignitaries of the same tribe were clustered around him, keeping order, and at the same time endeavoring to attract the attention of the vast assemblage to their own importance by industriously grating their teeth. It must have been an interesting occasion—perhaps a great bug jubilee commemorating the triumph of the locusts over Pharaoh’s crops in Egypt many centuries ago. At least, good seats, commanding an unobstructed view of the scene, were in great demand; and I have no doubt small fortunes were made by certain delegates from Yankee land by disposing of comfortable places on my shoulders at round premiums. In fact, the advantages which my altitude afforded were so well appreciated that I soon began to look like one of those big cards in the museum covered with insects impaled on pins.

The big “president” beetle (who, when he frowned, closely resembled Isbell when the pupils are out of time) rose and ducked his head and, crossing his arms over his shoulders, stroked them down to the tip of his nose several times, and after thus disposing of the perspiration, stuck his hands under his wings, propped his back against a lock of hair, and then, bobbing his head at the congregation, remarked, “B-u-z-z!” To which the congregation devoutly responded, “B-u-z-z!” Satisfied with this promptness on the part of his flock, he took a more imposing perpendicular against another lock of hair and, lifting his hands to command silence, gave another melodious “b-u-z-z!” on a louder key (which I suppose to have been the key-note) and after a moment’s silence the whole congregation burst into a grand anthem, three dignified daddy longlegs, perched near the gas burner, beating quadruple time during the performance. Soon two of the parts in the great chorus maintained silence, while a treble and alto duet, sung by forty-seven thousand mosquitoes and twenty-three thousand house flies, came in, and then, after another chorus, a tenor and bass duet by thirty-two thousand locusts and ninety-seven thousand pinch bugs was sung—then another grand chorus, “Let Every Bug Rejoice and Sing” (we used to sing “heart” instead of “bug”), terminated the performance, during which eleven treble singers split their throats from head to heels, and the patriotic “daddies” who beat time hadn’t a stump of a leg left.

It would take a ream of paper to give all the ceremonies of this great mass meeting. Suffice it to say that the little press “chawed up” half a bushel of the devotees, and I combed 976 beetles out of my hair the next morning, every one of whose throats was stretched wide open, for their gentle spirits had passed away while yet they sung—and who shall say they will not receive their reward? I buried their motionless forms with musical honors in John’s hat.

Now, Annie, don’t say anything about how long my letter was in going, for I didn’t receive yours until Wednesday—and don’t forget that I tried to answer it the same day, though I was doomed to fail. I wonder if you will do as much?

Yes, the loss of that bridge almost finished my earthly career. There is still a slight nausea about my stomach (for certain malicious persons say that my heart lies in that vicinity) whenever I think of it, and I believe I should have evaporated and vanished away like a blue cloud if John—indefatigable, unconquerable John—had not recovered from his illness to relieve me of a portion of my troubles. I think I can survive it now. John says “der chills kill a white boy, but sie (pronounced see) can’t kill a Detch-man.”

I have not now the slightest doubt, Annie, that your beautiful sketch is perfect. It looks more and more like what I suppose “Mt. Unpleasant” to be every time I look at it. It is really a pity that you could not get the shrubbery in, for your dog fennel is such a tasteful ornament to any yard. Still, I am entirely satisfied to get the principal beauties of the place, and will not grieve over the loss. I have delighted Henry’s little heart by delivering your message. Give the respected councilman the Latin letter by all means. If I understood the lingo well enough I would write you a Dutch one for him. Tell Mane I don’t know what Henry thinks of the verb “amo,” but for some time past I have discovered various fragments of paper scattered about bearing the single word “amite,” and since the receipt of her letter the fragments have greatly multiplied and the word has suddenly warmed into “amour” —all written in the same hand, and that, if I mistake not, Henry’s, for the latter is the only French word he has any particular affection for. Ah, Annie, I have a slight horror of writing essays myself; and if I were inclined to write one I should be afraid to do it, knowing you could do it so much better if you would only get industrious once and try. Don’t you be frightened—I guess Mane is afraid to write anything bad about you, or else her heart softens before she succeeds in doing it. Don’t fail to remember me to her—for I perceive she is aware that my funeral has not yet been preached. Ete paid us a visit yesterday, and we are going to return the kindness this afternoon. Good-by.

Your friend,

Sam [MTPO].

Sam befriended the Taylor girls, Annie Taylor, and sistersMary Jane Taylor (1837-1916), age nineteen and a student at Iowa Wesleyan University and Esther (“Ete”) Taylor (b.1836). They were the daughters of Hawkins Taylor (b.1810?), a former steamboat captain. At this time he was a prominent businessman, well thought of, highly literate and articulate. His interests included promoting education. It is likely that Sam admired such a man, and friendships with his daughters were valued. Powers and others claim Sam was in love with Annie, but Sam’s only surviving letter to her is signed “Your friend, Sam” [MTL 1: 62]. Interestingly, Paine in MTB does not write about Annie. May 24 Saturday – Esther Taylor (“Ete”), Annie and Mary Jane’s twenty-one-year-old sister paid Sam a visit [MTL 1: 62 & n9]

student at Iowa Wesleyan University and Esther (“Ete”) Taylor (b.1836). They were the daughters of Hawkins Taylor (b.1810?), a former steamboat captain. At this time he was a prominent businessman, well thought of, highly literate and articulate. His interests included promoting education. It is likely that Sam admired such a man, and friendships with his daughters were valued. Powers and others claim Sam was in love with Annie, but Sam’s only surviving letter to her is signed “Your friend, Sam” [MTL 1: 62]. Interestingly, Paine in MTB does not write about Annie. May 24 Saturday – Esther Taylor (“Ete”), Annie and Mary Jane’s twenty-one-year-old sister paid Sam a visit [MTL 1: 62 & n9]