Route 30. From Damascus to Beirût viâ Ba`albek.

From Damascus to Ba‘albek by Zebedâni 2 days, at Ba‘albek 1 day, to Shtóra 1 day, and to Beirût 1 day. Tolerable accommodation is obtainable at Zebedani, Ba‘albek, and Shtôra, so that this expedition may quite well be made without tents. French wine (dear) may be had at Ba‘albek and Shtóra, but other provisions should be taken for the journey. Those who travel with tents and have time to spare may spend a night at ‘Ain Fîjeh and another at Surghâya, reaching Ba‘albek in 2 ½ days In this case Sâlahîyeh and Jebel Kâsiûn (p. 487) may be visited for the sake of the beautiful view of Damascus.

As far as (3 M.) the post-station Dumar (p. 448) we follow the road of the French company.

[Or we may ride to (1 ¾ M.) Hemeh station ( p. 448), and thence to (¼ hr.) the village of Hemeh. (½ hr.) Jedeideh, (1 ½ hr.) Dêr Kânûn, (18 min.) El-Huseinîyeh, and (32 min.) Sûk Wâdy Barada (see below). The following route, however, is more interesting.]

Beyond Dumar we leave the road and turn to the right, past some white limestone hills (¾ hr.). The Barada gorge is too narrow here to be traversed. We next ride for an hour across the barren plain of Sahra (p. 448), a favourite resort of gazelles. To the right on the hill are rock-tombs; to the S. W. rises Mt. Hermon. We descend a small cultivated valley to the left, pass the village of El-Ashrafiyeh, and reach (25 min.) that of Bessîma, in the valley of the Barada. The fresh green of the trees near the river contrasts agreeably with the barren mountains. A curious rocky passage which connects Bessîma with Ashrafiyeh was probably once a channel for water, but it terminates suddenly at the W. end, and is traceable no farther. It possibly conducted the pure water of the Fîjeh springs to Damascus. It is on an average 2 ft. 8 in. wide, but varies in height, and the roof has been broken away at places; at other places there are open galleries affording an outlook towards the valley. The rock through which the passage runs is a limestone conglomerate.

The valley which we ascend is at first narrow; on the left is the small ‘meadow of Bessîma’, with beautiful verdure. The stream is bordered by poplars and fine walnut-trees. In ¼ hr. we reach a spring, and in 20 min. more the village and (5 min.) spring of El-Fîjeh, a name probably corrupted from the Greek ánoixi (spring). This is still regarded as the chief source of the Barada, though not the most distant, as it supplies that stream with twice as much water as it contains before it is thus augmented. The spring is a powerful volume of beautiful clear water, bursting from beneath ancient masonry, and hastening thence down to the Barada. Above the caverns containing the springs rises a kind of platform , consisting partly of rock and partly of masonry, with the ruins of a small temple built of huge blocks. A few paces to the S. of the spring run parallel walls, each 37 ft. long and 6 ft. thick, connected at the end by another wall 26 ½ ft. long and 3 ½ ft. thick. The whole edifice appears to have been vaulted over. Large stones project from the outsides of the lateral walls. and niches are traceable in the interior. In the direction of the river there was once a portal. The remains of this venerable shrine, which was perhaps dedicated to the river god only, are still enclosed by a grove of beautiful trees.

The path continues to ascend the valley, following the windings of the brook between barren cliffs 800—1000 ft. high. We soon come to (25 min.) the Dér Mukurrin, and (¼ hr.) Kefr Zét. We next perceive (10 min.) Dér Kânûn opposite to us on the right bank of the river, pass (¼ hr.) El-Huseinîyeh (p. 489), and reach (¼ hr.) Kefr el-`Awâmid, on an eminence near which are the ruins of a small Greek temple, consisting of columns, capitals, and fragments of a pediment. Beyond this we cross the river by a bridge, and reach the direct route (see above). On the right, below us, after 25 min., we perceive the village of Sûk Wâdy Barada.

The itineraries and other authorities indicate that Sûk Wâdy Barada occupies the site of the ancient Abîla, a town mentioned for the first time in the post-Christian period, the district around which was called Abilene. St. Luke mentions a certain Lysanias as having been tetrarch of Abilene in the fifteenth year of Tiberius (iii. 1). The other notices of the place, chiefly in the works of Josephus, are somewhat obscure. A tetrarchy of Abilene cannot have been established until B.C. 4, when the,inheritance of Herod the Great was divided, and it is quite possible that Lysanias, though not elsewhere named, governed the district eleven years later. The tetrarch must not be confounded with an earlier Lysanias, son of Ptolemy and grandson of Menneus. This Lysanias, who was prince of Chalcis (p. “A47), and may possibly have ruled over Abilene also,' was assassinated in B. C. 34 at the instigation of Cleopatra. — The tetrarchy of Abilene came into the possession of Herod the Great, and was afterwards presented by the Roman emperors to Agrippa I. and II.

The village of Sûk, surrounded by orchards, lies on a bend of the Barada, at the outlet of a defile which the stream has formed for itself between precipitous cliffs. Among the rocks above the village, on the opposite bank of the stream, are seen a number of rock-tombs, some of which are inaccessible. Others are reached by steps. These tombs contain nothing noteworthy. Abila is popularly derived from ‘Abel’, and on the hill to the W. (right) a tradition of the 16th cent. points out the Neby Hubîl as the spot where Cain slew his brother (according to the Korán version). The building itself is uninteresting. Adjacent are the ruins of a temple, about 15 yds. long and 8 ¾ yds. wide. At the E. end of the temple is vaulted tomb with steps in the rock near it. — We reach the bridge at the narrowest point of the gorge, 10 min. above the village. On the opposite (left) bank, by climbing upwards a little above the bridge, we reach an ancient road skirting the cliff about 100 ft. above the present path. This road, which is 13—16 ft. wide, is hewn in the rock for a distance of 300 paces. At places a ledge of rock has been left to form a parapet, and the other parts of the road were probably protected by a wall. At the N.E. end the road terminates in a precipice, whence it was perhaps carried onwards by a viaduct. Latin inscriptions on the neighbouring wall record that this road was constructed during the reigns of the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (i. e. a little after the middle of the 2nd century) by the legate Julius Verus at the expense of the inhabitants of Abila. A few paces below the road runs an ancient conduit, partly hewn in the rock and covered with obliquely placed stones. It may be used as a means of access to some of the rock-tombs.

Beyond the bridge we follow the course of the stream on its left bank. The slopes become less precipitous (10 min.), and the valley at length expands into a small plain (10 min.), where the brook forms a waterfall. A little above the fall are remains of an old bridge. The stream is here augmented by the discharge of the Wâdy el-Karn (p. 448), coming from the S.W. A path leads hence to the French road, 1 hr. distant. Ascending, we ride round the hill to the right, and suddenly come upon the lower part of the Plain of Zebedâni, which stretches from N. to S. between mountains of considerable height. The steep hill to the W. is the Jebel Zebedâni. The plain, which was probably once a large lake, is nearly 3 M. broad, and beautifully cultivated and well watered. It is covered with apple, apricot, and walnut-trees, poplars, etc., and some of the gardens are enclosed by green hedges. ‘Traversing this luxuriant region, we next reach (2 hrs. 20 min.) the village of Zebedâni, situated in the midst of exuberant vegetation, with 3000 inhab., who live on the produce of their gardens, half of them being Christians. (Quarters may be obtained at the houses of the Christians or at the Khan.) The apples of Zebedâni are famous, and the oval grapes are common here, but there are no antiquities.

Beyond Zebedâni we ascend the valley; after ½ hr. the road is joined by that from Blûdân (p. 493), coming from the right. The spring of ‘Ain Hawar, with the village of that name remains on the right (25 min.); we then cross the watershed and arrive (1 hr.) at the village of Surghâya, in a verdant but confined situation.

On the spur of the hill to the E., by the village of Surghâya, some rock-tombs are visible. By the wayside, at the beginning of the ascent, is a fine wine or oil press, hewn in the rock. The tombs contain six arches with niches for the sarcophagi. Beyond the rock are slight remains of a village. Near a large oak are several other rock tombs.

After 28 min. we descend from the large spring in the middle of the village to the Wâdy Yafûfeh, where there is a ruined khan. The brook is crossed here by a bridge called Jisr er-Româneh. The sides of the valley are lofty and precipitous.

Three different routes lead from this bridge to Ba‘albek, of which the following is the pleasantest:: —

We descend the valley to the left on its right bank, and after 16 min. cross the brook again. The bottom of the valley is covered with oaks, planes, and wild rose-bushes. After 14 min. we cross a third bridge. The village of Yafûfeh lies a little lower down, on the left. We then ascend the hill, avoiding a path to the left. On the top of the hill (23 min.) is revealed a beautiful view of Lebanon and the Beka‘a. To the N. the snowy peaks of the Sannin contrast effectively with the red earth of the valley, the N.W. part of which is wooded. A village, with the Neby Shît (Seth), remains to the left. The view continues beautiful. The route pursues a straight direction, passing many cross paths. After 1 ¼ hr. we see the village of Khortdâneh below us on the left, and we ride through a deep valley. After 28 min. we pass near the village of Brithén (probably the ancient Berothai: 2 Sam. Viii. 8), which lies behind a hill about 10 min. to the right. After 37 min. we reach the deep Wâdy et-Tuyyibeh, in 35 min. more avoid a path to the right, and reach (10 min.) the village of `Ain Berdai, beyond which (4 min.) we soon perceive the gardens of Ba‘albek and its acropolis, the large columns being especially conspicuous. In 11 min. we reach the broad road coming from the left, and in 7 min, more the first houses of the village.

The two other routes from the Jisr er-Rumâneh (see above) to Ba‘albek are the following: —

a. A steep path ascends immediately beyond the bridge to (1 hr. 20 min.) the village of Khureibeh, passes (1 hr. 50 min.) near Brithén (see above) and on this side of it unites with the above route.

b. Another path ascends from the bridge on the left bank of the brook to (20 min.) the ruins of a small temple, and passes (] hr.) the ruined village of Ma‘rabûn, with a spring, on the hill to the right. The slopes of the valley to the right are very steep, but partially wooded, like the hills to the left. The floor of the valley here forms a small plain. We then ascend the Wâdy Ma‘rabún to the N., crossing the bed of the brook several times. After 2 hrs. we come to the valley of Sha‘íbeh, in the midst of wild scenery. The village remains to the right. We next pass (½ hr.) a valley descending to the left to Et-Tayyibeh, and then (¼ hr.) some ruins, and (1 hr. 10 min.) reach the spring of Ba‘albek (p. 500).

From DAMASCUS TO ZEBEDÂNI (AND BA‘ALBEK) BY HELBÛN. Starting from the cross-road outside the Bâb Tûma (p. 481) we follow the Aleppo road towards the N., diverging from it to the left after 11 minutes. We still ride between mud-walls and under the shade of lofty walnut-trees, and after 9 min. avoid a path to the left. Near a brook and an olive press we at length emerge from among the gardens (14 min.). About ½ hr. to the right is the village of Kabûn. Anti-Libanus is seen hence, stretching as far as the rounded hill of Theníyeh. To the left still rise the steep, bare rocks of the Jebel Kâsiún (p. 487). We pass (9 min.) a reservoir on the left, and reach (10 min.) the village of Berzeh. A Muslim legend makes this the birthplace of Abraham, or at least the point to which he and his servants penetrated in this direction (Gen. [xiv. 15). Here we turn to the left, and in 8 min. reach the entrance of a gorge, where the vegetation ceases. The gorge is so narrow that we have to ride in the bed of the brook, which however in summer is nearly or quite dry. In 33 min. we quit the ravine and cross a bridge. After 6 min. we see the village of Ma‘raba on the hill to the left. Ascending the course of the principal stream, we may now traverse the beautiful valley of Helbûn, which is dry in summer, to (1 ½ hr.) ‘Ain es-Sâhib, and (40 min.) Helbûn (see below).

We prefer, however, making a pleasant digression from Ma‘raba through the side-valley to the N. to Menin, passing through rich vegetation. After 27 min. we see the village of Herneh on the left, beyond which, on the hill to the right, is a wely, and on the left a mill, surrounded by trees. We pass (13 min.) the village of Et-Tell, and (27 min.), near a grove of poplars, cross a brook, beyond which we pass a small gorge and (15 min.) a mill on the left. In 4 hr. more we reach the village of Menin. The rocky slope by the spring beyond the village affords a good, shady resting place. The rock-tombs above Menin show the antiquity of the place. The village is now inhabited by Muslims only. On the E. hill (ascent of ½ hr.) are remains of ancient buildings and rock chambers. In front of these caverns, which were probably also used for religious purposes, are seen the remains of a temple. The view embraces part of Anti-Libanus, and also, through a gap in the bare rocks, a portion of the Ghûta, or plain of Damascus (p. 465), stretching as far as the Haurân Mts.

The road from Menin to Helbûn leads immediately to the W. from the spring, turns to the left after 3 min., and to the right in 1 min. more. Menîn looks very picturesque from this point. On the left, after ¼ hr., we look down into the Wâdy Deréj (Helbûn), into which we soon descend (20 min.). On the left lies the village of Deréjy. We then reach (12 min) the path which ascends direct from Ma‘raba, and near ‘Ain es-Sahib we pass between the rocks on the right. On the hill adjoining this romantic defile, which is traversed by a small brook, we observe some rock-tombs, one of them with columns and a bust. The path skirts the left side of the valley which is enclosed by considerable heights, passes (28 min.) a spring, and (12 min.) reaches the village of Helbûn.

Ezekiel (xxvii. 18) mentions Helbon as the place whence Tyre obtained her wine through the agency of the merchants of Damascus, and this appears to agree with the statement of Strabo (and Athenæus) that the kings of Persia imported their wine from ‘Chalybon’. The country is admirably adapted for the culture of the vine, the valley being bounded by vast slopes of fine chalky rubble. Some of these are still covered with vines, but the grapes are now all dried to form raisins. Helbiin lies at a bend of the valley, at the foot of steep hills which are scantily clothed with green; and a small side valley descends here to the main valley from the N.W. The floor of the latter is covered with trees. The village is Muslim. Fragments of columns and ancient hewn stones are built into the houses and garden walls. The mosque in the middle of the village is recognisable by its old tower; in front of it is a kind of colonnade, with columns composed of numerous fragments of stone. A copious spring wells forth from below the mosque into a basin. Fragments of Greek inscriptions are to be found here.

Beyond Helbûn the steep path ascends the left side of the valley through a wild region. After 22 min. we see caverns resembling tombs on the hill to the left, and then descend to the abundant spring ‘Ain Fakhûkh in the valley (4 min.). Our route follows the main valley, avoiding a path to the right, traverses plantations of sumach (Rhus coriaria), and reaches (26 min.) a bifurcation where we ascend to the right. The hills are scantily covered with bushes. After 43 min. we obtain a survey of the plain of Damascus, and in 17 min. descend into a valley, the bottom of which is cultivated (26 min.). The road again ascends to the right, and reaches (24 min.) a small table-land. After 12 min. we see the chain of Lebanon, and soon afterwards Zebedâni in the valley, and ‘the Sannin to the N., while Mt. Hermon is visible towards the S. in all its majesty. We descend to (5 min.) the village of Blûdán (4847 ft. above the sea), which contains European houses used as summer residences by the English consul at Damascus and the American missionaries. From Blûdân we reach Zebedani in 40 minutes. In order to reach the Ba’albek road, we descend to the N., and after 23 min. reach the end of the orchards. After ½ hr. our road is joined by one from the right, and in 5 min. more by that from Zebedâni (p. 491) from the left.

Ba‘albek. Tolerable quarters are obtainable in the first houses to the right of the road. Those who have tents should pitch them in the Acropolis itself.

History. Ba‘albek (ancient Syrian Ba‘aldakh) is undoubtedly the Heliopolis of Greco-Roman authors, but we possess no written records regarding the city earlier than the 3rd or 4th cent. of our era. The Greek name suggests that the place was connected with the worship of the sun, and Baal was nearly identical with the god of that luminary. Coins of Heliopolis of the 2nd and 3rd cent. show that the town was a Roman colony. Coins of Septimius Severus (193—211), however, no longer bear the earlier device of a colonist with an ox, but the outlines of a temple, or rather of two temples, a greater and a smaller. This confirms a statement dating from the 7th cent. to the effect that Antoninus Pius erected a large temple to Jupiter at Heliopolis in Phœnicia, which was regarded as one of the marvels of the age. Later coins also bear representations of the two temples, but it is unknown whether the larger was ever finished. From the votive inscriptions of Antoninus Pius it would appear that the larger temple was dedicated to all the gods of Heliopolis; the smaller would therefore be the temple of Baal. Both temples most probably date from the same period. Besides Baal. Venus was also specially revered at Heliopolis, but the worship of these deities is said to have been suppressed by the emperor Constantine, who erected a basilica here. Both before and after Constantine the Christians were persecuted at Heliopolis. Theodosius the Great (8379—395) destroyed the great “Trilithon’ Temple at Heliopolis and converted it into a Christian church. At a later period bishops of Heliopolis are mentioned. Ba‘albek was conquered by Abu ‘Ubeida on his march from Damascus to Homs. The Arabs extol the fertility of the environs, and attribute the antiquities to Solomon. The Arabic name corresponds with the earlier Syrian appellation of the place. The Arabs mention Ba‘albek specially as a fortress and at an early period they converted the acropolis into a citadel. As a fortress it was important in the wars of the middle ages, as, for example, in the conflicts between the Seljuks and the sultans of Egypt. In 1139 the town and castle were captured by Emir Zenghi. and during the same century the place suffered from several earthquakes. In 1175 the district of Ba‘albek came into possession of Saladin. In the following year the Crusaders under Raymund made an expedition from Tripoli to the neighbourhood of Ba‘albek, defeated the Saracens, and returned laden with booty. Baldwin 1V. undertook a similar expedition from Sidon. In 1260 Ba’albek was destroved by Hûlagû, and was afterwards conquered by Timûr. In the middle of the 16th cent. the ruins of Ba‘alhbek were rediscovered by Europeans, but they have again suffered severely from earthquakes, particularly that of 1759.

Ba‘albek (3839 ft. above the sea) lies on the E. side of the valley of the Lîtâny (p. 449), which is here very fertile. Not far distant is the watershed between this river and the El-‘Asi ( Orontes).

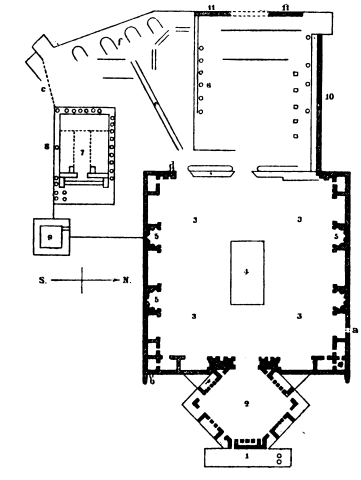

The Acropotis of Ba‘albek, surrounded by gardens, and running from W. to E., rises to the W. of the little town. One entrance is by a breach (Pl. a) in the wall on the N. side, to which the visitor ascends over loose stones (the best, as it leads at once into the great court of the temple); another entrance is by a vault (Pl. b) at the S.E. corner. A door (Pl. c), through which there was a direct approach to the temple of the sun. is now walled up.

The vaults are spacious, and some of their side-chambers were probably used as stables and warehouses in the middle ages, as they are to this day. They consist of two long, parallel, vaulted passages, intersected by another, and bearing remains of Latin inscriptions. The latter, as well as the style of construction, point to a Roman origin.

We shall appreciate the plan of the edifice best by beginning our inspection of the interior at the W. end. Passing through the breach (Pl. a)

a. Breach. b & d. Entrances to the vaults. c. Entrance now built up.

1. Portico.

2. Hexagonal Forecourt.

3. Large Court.

4. Raised Platform.

5. Ezedra.

6. Preserved Columns of the Great Temple.

7. Temple of the Sun.

8. Half-recumbent Column.

9. Arabian Building.

10. External Wall.

11. Cyclopean Wall.

we turn to the left, traverse an open passage to an entrance-court, aud pass through a low door into a second entrance court. We thus reach the Portico (Pl. 1) of the great temple. The level of the floor being 19 ft. above the adjoining orchard, it is supposed that the temple was approached from this E. end by a broad flight of steps, the materials of which were probably used in the construction of the mediæval citadel and the present E. wall. The portico is a rectangle of about 12 yds. in depth. In front it had twelve columns, the bases of which are still preserved. Two of these bear Latin inscriptions to the effect that the temple was erected and dedicated by Antoninus Pius and Julia Domna. The portico is flanked by tower-like buildings, enriched externally by a moulding running round them at the same height as that of the portico. There are also doors leading into square chambers, which are richly adorned with pilasters, niches, etc. The upper parts of these buildings were converted into fortified towers in the middle ages. The northern tower is better preserved than the southern.

In the richly decorated wall at the back of the porch are three portals, the central and largest of which is 23 ft., the two smaller 10 ft. wide. The small portal on the l. side only is now open. The Court (Pl. 2) which we now enter is of hexagonal form, about 65 yds. long, and from angle to angle about 83 yds. wide. The foundation walls and a few shell-shaped niches are alone preserved. On each of the six sides, except the western, there were originally square exedræ, or lateral chambers, in front of each of which there stood four columns. The eastern exedra was entered from the portico. Between these exedra lay smaller chambers of irregular shape. — From this point we can observe the buildings constructed by the Saracens on the E. side.

A threefold portal led from the hexagon into the large and handsome Entrance Court (Pl. 3) of the temple. The smaller northern portal only is preserved (on the right). This court is about 147 yds. long from E. to W., and 123 yds. wide. On both sides of the court, and at the E. end, there are also exedre, which are best surveyed from the square platform (Pl. 4) in the centre of the court. ‘The fragments in the middle which are still preserved probably belonged to a basilica. The court presents an effective ensemble, but on closer inspection the degenerate style of the ornamentation points to the late period of the 3rd century, and particularly in the case of the exedre. These generally contain two rows of niches, one above the other, and there are others in their partition walls. The niches are separated from one another by Corinthian pilasters with highly ornate capitals, but their forms differ greatly. Some of them are in the shell form, others are semicircular, with carved beams, and others again have broken gables. The best preserved exedra is one of semicircular form (Pl. 5) on the N. side. Many of the niches on the other sides are destroyed. The exedre were all covered, and in some of them interesting remains of the moulding of the ceiling are preserved. In front of the chambers ran rows of columns, some of syenite. a few of which still lie scattered about (in the S. part of the court). The chambers on both sides correspond exactly with, each other, so that we need describe one side only. Adjoining the smaller entrance portal on the right, which is still preserved. We first find a large niche, perhaps destined for a colossal statue, beyond which comes a rectangular chamber. In the N.E. corner of the court are three quadrangular chambers, that in the angle being accessible from the side chambers only. On the N. side we next come to a square chamber (originally with four columns). Next is a semicircular chamber (with two columns), beyond which, in the centre of this side, is a long rectangular chamber, followed by a corner chamber. Adjoining the last, at the N.W. corner, there is still preserved a shell niche, forming a sort of portal.

Of the Great Temple (PI. 6), the entrance courts of which we have just traversed, but few remains are now extant. The six huge columns of the peristyle, the sole remains of the once world-renowned temple, have already long been visible to the traveller approaching Ba‘albek. The yellowish stone of which they are com posed looks particularly handsome by evening light. The columns are about 60 ft. in height, and are still provided with stylobates. The bases of the columns and the Corinthian capitals are somewhat heavily executed. The architrave is in three sections. Above it is a frieze with a close row of corbels, which appear to have borne small lions. Still higher is tooth moulding, then Corinthian corbels, and still higher a cornice, in all 17 ft. high. The smooth shafts are 74 ft. in diameter, and consist of three pieces held together with iron. The Arabs and Turks have barbarously made incisions in the columns at several places in order to remove the iron cramps, and it is to be feared that the columns, being much ‘undermined , and being damaged in the upper parts also, will not stand much longer. — These six columns formed part of the peristyle, which had nineteen columns on each side and ten at each end; but of these nine only were standing in 1751. Many columns now lie scattered around. The form of the temple which was thus enclosed cannot now be determined. It faced the E., and stood on a basement about 50 ft. above the surrounding plain. The E. wall of this substruction adjoined the platform of the entrance court; the S. wall is partly buried in rubbish. The W. wall is covered with masonry, and about the middle of it there is a gap, through which we look down upon gardens. ‘The N. wall, above which a few fragments of columns are still inserted, is exposed to view, and consists of thirteen courses of drafted stones, each course being 33 ft. high. Outside these walls, and 29 ft. distant from them, runs an enclosing wall of large hewn blocks (p.*499).

If we proceed towards the S.E. from the six columns, the entrance (Pl. d) to the above mentioned subterranean passage remains on the left, and we reach the so-called Temple of the Sun (Pl. 7), the smaller of the two. It stands on a basement of its own, lower than, and quite unconnected with, the larger temple. It contains no court, but was approached from the E. by a stair ascending direct to the portal. The stair was flanked with walls, and part of it still perhaps exists under the walls of the Turkish fort built in front of it. —- This temple is one of the best preserved and most beautiful antiquities in Syria. It is surrounded by a peristyle, partially preserved, which consisted of fifteen columns on each side, and eight at each end. In front of the portal there was a double row of columns; and on each side, in front of the projecting walls which formed the portal, stood a fluted column. Of this E. row of columns the bases only are preserved, except on the S. side, the rest being concealed by the Turkish walls. The columns of the peristyle and the wall of the cella are 10 ft. apart. The columns, including the Corinthian capitals, are 464 ft. in height, and bear a lofty entablature with a handsome double frieze. The entablature is connected with the cella by large slabs of stone, which form a very elaborately executed coffered ceiling, consisting of hexagons, rhomboids, and triangles with central ornaments, while the intervening spaces are filled with busts of emperors and gods relieved by foliage. The leaf work is beautifully executed, resembling the Byzantine style in its treatment.

Four connected columns are preserved on the S. side, but of the others the bases only are left. Most of the fragments of the shafts have been thrown down from the platform. One column (Pl. 8) has fallen against the cella, and so strongly is it held together with its iron cramps that it has broken several stones of the wall of the cella without itself coming to pieces. The wall, however, is in a precarious condition. Here, too, the Turks have destroyed the shafts and bases of the columns in order to extract the iron. On the W. side three columns are still upright, and connected with each other; but of the others fragments alone remain. Huge masses of the coffered ceiling have fallen in, one of the finest fragments being a female bust surrounded by five other busts. The peristyle on the N. side is almost entirely preserved. Its ceiling consists of thirteen more or less damaged sections with fine busts.

INTERIOR. Traversing the porch, which is 25 ft. deep, we come to the very elaborately executed Portal of the temple, the gem of the structure. It was rectangular in form, and on each side stood columns. The doorposts are huge monoliths, lavishly enriched with vines, garlands, genii, and other objects. The architrave consists of three stones, on the lower side of which is the figure of an eagle with a tuft of feathers, holding in its claws a staff and in its beak long garlands, the ends of which are held by genii. The eagle was probably a symbol of the sun. The central stone having subsided since 1659, it lately became necessary to prop it ( permission having been obtained by Mr. Burton, the English consul, after troublesome negociations with Reshîd Pasha in 1870), whereby its appearance has been impaired. On each side of the entrance are massive pillars containing spiral stairs. The entrance to one of these is built up, but in the other pillar about eighteen steps upwards and a few downwards have been preserved. The cella, about 29 yds. long and 244 yds. broad, is half destroyed. Above a cornice there were five niches, of which three are preserved. The N. side is less injured than the S.; on each side are eight fluted half-columns with projecting entablature. The different sections of the architrave project considerably, one beyond the other. The building was once covered with vaulting. The frieze is subdivided by triglyphs closely ranged together. The empty rectangular niches are crowned by small projecting gables. The curved and enriched architrave over the lower series of arches is worthy of inspection. At the W. end was the raised sanctuary, where the altar stood during the Christian period. Portions of the partition wall are still preserved. A door descended hence to vaults. — Interesting as the details of the structure are, the effect of the whole points to a late period of art.

Opposite the facade of this temple stands an Arabian building (P1. 9) with a stalactite portal. The steps ascending to it are destroyed. The vaults and chambers in the interior are uninteresting.

Leaving the Acropolis, we now take a walk round the enclosing Wall. At the N.E. corner the wall of the quadrangular court rises about 19 ft. higher than the outer wall. Below this raised part of the wall a large portal led into the underground vaults. Above this portal is a second door, with Corinthian pillars, now built up. The N. wall, which is here about 19 ft. high only, was probably unfinished. On this N. side a gate leads into the intervening space between the outer wall and that which forms the substruction of the peristyle of the great temple. Fragments of the columns of the peristyle are still lying here. The outer wall (Pl. 10) is here 10 ft. thick, and contains nine stones, each about 30 ft. long. These, however, are small compared with the stupendous blocks in the W. wall (Pl. 11), which are perhaps the largest stones ever used in building. One of these is about 64 ft., another 634 ft., and a third 62 ft. in length; each of them is about 13 ft. high, and probably as many feet in thickness. The greatest marvel is that they have been raised to the top of a substruction already 19 ft. high. By whom, and by what machinery they were quarried and placed in their present position will probably never be ascertained. The lower stones are grey, and the large blocks yellowish, in colour. It was probably from these three extraordinary blocks that the temple derived its name of trilithon (‘three-stoned’).

In the modern village, to the E. of the Acropolis, is a third Temple, smaller, and well preserved. We ascend the street of the village, and near a picturesque little tower with water flowing past it we perceive the outside of the temple. In order to visit it we must either climb over a wall on the W. side, or pay a few piastres for admission through a house on the N. side of the temple. The outside is the most remarkable part of this temple. The cella is semicircular in form. Around it runs a peristyle of eight beautiful Corinthian monolithic columns. Between these, in the wall of the cella, are shell niches, with a curved architrave borne by small Corinthian pilasters. Along the upper part of the wall of the cella runs a frieze with wreaths of foliage. The architrave and the entablature of the peristyle are bent inwards semicircularly, and project from the wall of the cella beyond the columns of the peristyle. The entablature is lavishly enriched with tooth ornament and other decoration. The doorposts of the portal consist of large monoliths. In the interior are three niches, two with round architraves, and one with a triangular one. The building was formerly used as a Greek chapel, but is now rapidly falling to decay.

ENVIRONS OF BA‘ALBEK. In the hills to the S.E., near the road to Zebedâni, and 16 min. from Ba‘albek, are the ancient Quarries, where another colossal hewn block (hajer el-kibla), probably likewise destined to be used in the construction of the outer wall of the Acropolis, but not yet separated from the rock, is still to be seen. Its prodigious dimensions are only appreciated on closer inspection. It is 71 ft. in length, 14 ft. high, and 13 ft. wide, and would probably weigh 1500 tons. How such blocks were transported in ancient times is, and probably will always remain, a mystery. In the vicinity are other large stones partially excavated. — We now ascend the hill to the S.E. of Ba‘albek. At the top we enjoy an admirable survey of the little town, the Acropolis, the beautiful wide plain with its red earth (coloured with oxide of iron), the summit of the Sannin, and to the N. of it the Munétireh mountain, with its wooded slopes. To the E., in the small valley separating this spur from Anti-Libanus, is the spring Râs el-‘Ain. On the hill are the remains of a Muslim chapel, and higher up is a tomb surrounded with fragments of columns. A capital belonging to one of these lies about eighty paces lower down the W. slope. — The old town walls of Ba‘albek skirt the slopes of this hill. Following the slope towards the N.E., we come to a heap of fragments of columns, and in a few minutes to large rock-tombs extending along the N.E. slope, still inadequately explored. (From this point we may return through the small town.) Or following the hill to the right, we may proceed to (20 min.) Rés el-‘Ain. A copious brook here bursts from the earth, and is enclosed in a basin. Adjacent are the ruins of two mosques. The smaller was built, according to the inscription, by Melik ed-Dáhir in 670 of the Hegira (1272), and the larger by his son Melik el-As‘ad. The outer wall of the latter is still standing.

To the N.W. of Ba‘albek stands a large barrack (kishlak), of the time of Ibrahim Pasha, and beyond it are several deserted buildings. To the right lies a rocky region containing numerous quarries, with stairs hewn in the rock. There are also several caverns, which were probably used as tombs.

From BA‘ALBEK TO SHTÔRA (about 7 hrs.). The route leads to the S.W. of Ba‘albek, avoiding that to ‘Ain Berdai und Tayyibeh (p. 492) to the left. On the right (½ hr.) we pass a ruin named Kubbet Dûris after the neighbouring village of Dûris. It is a modern wely, built of ancient materials, and adorned with eight fine columns of granite, over which the builder has ignorantly placed an architrave. A sarcophagus standing on end was used as a recess for prayer. The plain of Bekâ‘a (p. 447), which we traverse obliquely, is destitute of trees, and its steppes are used as pasturage for cattle. In 1 hr. 40 min. we reach the village of Tallîyeh, in 1 hr. 10 min. the bridge across the Lîtâny at Tell esh-Sherîf, and in 1 hr. 10 min. more the village of Temîin et-Tahta at the foot of Lebanon.

At Kasr Nebâ, about 1 hr. to the N. of this village, are the ruins of a temple, and there are similar ruins at Nîha, about 1 hr. to the W., but both buildings are almost entirely destroyed. A better preserved temple is that of Hosn Nîha, 1 hr. above the village of Nîha, situated in a small valley 4200 ft. above the sea, or 1200 ft. above the plain. The temple looks towards the E., and stands on a basement 11 ft. high, which on the E. side projects 27 ft. It is approached by steps. The temple was a prostylos of the Corinthian order, and was 31 yds. long and 13 ½ yds. wide. The W. end of the cella is raised. — In the valley of Temnîn et-Tahta, at the E. base of Lebanon, there are about 200 rock-tombs in the Phoenician style.

Leaving Temnîn et-Tahta, and skirting the base of the hills, where several villages are seen, we reach (1 hr.) Kerak Nûh, where the tomb of the ‘Prophet Noah’ is shown (44 yds. in length). The recently improved road next leads to the (7 min.) village of Mu‘allaka (Inn), inhabited almost exclusively by Muslims (accommodation may be obtained in the new building of the Jesuits at the E. end of the village, pleasantly situated in a garden). Mu‘allaka, which belongs to the Syrian province of Damascus, lies contiguous to the large village of Zahleh, which belongs to Lebanon, being separated from it by a narrow street only.

Zahleh (3100 ft. above the sea) contains about 15,000 inhab., chiefly Christians, among whom the Maronites predominate, an English school, and a Turkish telegraph office. The village nestles amidst beautiful vegetation, lying partly on the slope. It is surrounded by orchards, is the most important wine-growing place in Lebanon, and boasts of busy manufactories. The brook El-Berdûni descends through a gorge from the Sannîn. The inhabitants are noted for their turbulence. In 1860 they suffered terribly, as the Druses took the town and concentrated their forces there.

The ascent of the Sannin (8557 ft.) may be undertaken from Zahleh With good guides. The route is precipitous. At the top are the ruins of a temple. Towards the W. the eye ranges over numerous valleys descending to the sea. The hills above Zahleh are partly wooded with Cypresses.

From Mu‘allaka we descend between mulberry-trees into the gorge, and in about 1 hr. reach Shtóra (p. 447) by a good road. Thence to Beirût, see p. 446.