Misery loves company. Now and then at night, in out-of-the way, dimly lighted places, I found myself happening on another child of misfortune. He looked so seedy and forlorn, so homeless and friendless and forsaken, that I yearned toward him as a brother. I wanted to claim kinship with him and go about and enjoy our wretchedness together. The drawing toward each other must have been mutual; at any rate we got to falling together oftener, though still seemingly by accident; and although we did not speak or evince any recognition, I think the dull anxiety passed out of both of us when we saw each other, and then for several hours we would idle along contentedly, wide apart, and glancing furtively in at home lights and fireside gatherings, out of the night shadows, and very much enjoying our dumb companionship.

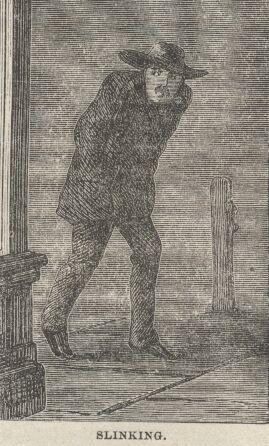

Finally we spoke, and were inseparable after that. For our woes were identical, almost. He had been a reporter too, and lost his berth, and this was his experience, as nearly as I can recollect it. After losing his berth he had gone down, down, down, with never a halt: from a boarding house on Russian Hill to a boarding house in Kearney street; from thence to Dupont; from thence to a low sailor den; and from thence to lodgings in goods boxes and empty hogsheads near the wharves. Then; for a while, he had gained a meagre living by sewing up bursted sacks of grain on the piers; when that failed he had found food here and there as chance threw it in his way. He had ceased to show his face in daylight, now, for a reporter knows everybody, rich and poor, high and low, and cannot well avoid familiar faces in the broad light of day.

From Pages 282 The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871:

Then a crucial moment, if not in Sam’s life then in the narrative he constructed about his life: “I remember a certain day in San Francisco,” he recalled in 1901, when at the absolute nadir of his fortunes he picked up a dime at the corner of Commercial and Montgomery Streets. If he had not found that dime, “I should have asked someone for a quarter. Only a matter of a few hours and I'd have been a beggar. That dime saved me, and I have never begged—never!” Similarly, in chapter 59 of Roughing It, he chronicles the adventure of a “mendicant” who “had been without a penny for two months’ before he finds a silver dime in the street.” At first glance, in reporting this incident Sam seemingly affirmed republican values that discouraged vagrancy, These values were ironically at odds with the mining ethos of wealth quickly gathered and squandered as well as his ambition to get rich by trading mining stock rather than by manual labor. Sam occasionally qualified his praise for the republican and working-class virtue of industry, however, by advocating the exploitation of Chinese workers (“The sooner California adopts Coolie labor the better it will be for her”) and convicts: “In America we make convicts useful at the same time that we punish them for their crimes. We farm them out and compel them to earn money for the State by making barrels and building roads. Thus we combine business with retribution, and all things are lovely.” He also contradicted the labor theory of value in retelling the story of his discovery of the coin in the street in his autobiography: the “dime gave me more joy, because unearned, than a hundred earned dimes could have given me.” Even in Tom Sawyer, Sam implicitly commends Tom for tricking Ben Rogers and several other village boys into whitewashing a fence in his stead, in effect valorizing Tom for exploiting them.

But Sams discovery of the dime in the street enabled him to buy a decent meal and anticipates several comments about beggars in later writings that betray his “reactionary social politics,” to use Peter Messent’s phrase. Though Sam might have been forced to panhandle had he not found the dime, he was nevertheless disgusted by the beggars he encountered in Italy, Morocco, and Palestine during his Quaker City cruise in 1867.

…

In a letter to the editor of the Hartford, Connecticut, Evening Post in January 1873, even before the financial panic in September that precipitated a long economic depression, Sam belittled the “able-bodied tramps who are too lazy to work.” In a similar letter to the editor of the Hartford Courant in September 1875, he scoffed at the claims of a stranger who had appealed to him for a contribution to support a school for freed slaves in the South. Sam admitted he had either “been unjust to a stranger today” by dismissing him out of hand “or unfaithful to my duty as a citizen, I cannot yet determine,” but he planned to investigate. If the stranger's references “fail to establish his worthiness,” Sam added, “I will publish him and also try to procure his arrest as a vagrant.”

From Pages 292 The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871:

“When my credit was about exhausted,” [possibly June 20, 1865, see DBD] Sam remembered in Roughing It, “I was created San Francisco correspondent of the Enterprise.” Joe Goodman rehired him in early June at a salary of a hundred dollars a month. In effect, he closed a circle: once the Virginia City correspondent of the San Francisco Morning Call, he now became the San Francisco correspondent of the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise. For the next eight months, as Goodman declared in December 1900, Sam submitted “the best work he ever did” to the paper. A. B, Paine echoed the sentiment: Sam contributed “the greatest series of daily philippics ever written” to the Enterprise, high praise indeed considering that only about 20 percent of the 150-plus columns survive whole or in part.

The Earthquake of ...

At 12:48 p.m. on Sunday, October 8, 1865, Sam experienced his first earthquake, one of the strongest temblors recorded in San Francisco prior to the devastating quake of April 1906. He was walking along Third Street and had just reached the corner of Mission when suddenly “there was a great rattle and jar, and it occurred to me that here was an item!—no doubt a fight in that house. Before I could turn and seek the door, there came a really terrific shock; the ground seemed to roll under me in waves, interrupted by a violent joggling up and down, and there was a heavy grinding noise as of brick houses rubbing together.’ As he “reeled about on the pavement trying to keep my footing, I saw a sight!” The entire front of L. Poppet’s four-story brick building, under construction on the southeast corner of the intersection, collapsed and splattered into the street, “raising a dust like a great volume of smoke!” Sam leaped against a wall for protection from the falling debris. “No one else saw it but me,” he remembered, and “I never told anyone about it.”°’ He detailed these incidents in his next letter to the Enterprise, though he mostly ignored the deaths and property damage to crack wise. At the moment of the tremor, according to Sam, Horatio Stebbins left the pulpit of the First Unitarian Church “and embraced a woman. Some say it was his wife.” Pete Hopkins, the old adversary he murdered in the “bloody massacre” hoax, ' narrowly escaped injury’ when he fell “from the summit of Telegraph Hill” onto “a three-story brick house ten feet below.” In another account of the events, Sam reported that a brick warehouse near the docks had been “mashed in as if some foreigner from Brobdignag had sat down on it.” His piece in the Enterprise was accompanied by several scare headlines, such as “San Francisco Half in Ruins” and “Loss of Life and Numerous Instances of Injury,’ that the San Francisco press reproved.

Page 296 The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871: