Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travelers

We are informed by the Bible that Golgotha lay outside the city (Matth. xxviii. 11+; Hebr. xiii. 12). This was an eminence, or perhaps only a small rocky protuberance, called on account of its peculiar shape *gulgolta' (skull) in Aramaic, of which Golgotha is the N. T. form. It is still unknown whether the eminence was a natural or artificial one. To the N. and S. of the place pointed out by tradition the ground dips gradually. The first point of controversy among scholars is whether the genuine Golgotha lay in this neighhourhood or not. Several English explorers look for Golgotha to the N. of the town, near the grotto of Jeremiah (p. 101), but until farther excavations are made nothing certain can be known. Bishop Eusehius of Cæsarea (264-340 A.D.), the earliest historian who gives us information on the subject, records that during the excavations in the reign of Constantine the sacred tomb of the Saviour was, 'contrary to all expectation1, discovered. Later historians add that Helena, Constantine's mother, prompted hy a divine vision undertook a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and that she and Bishop Macarius, by the aid of a miracle, there discovered not only the Holy Sepulchre, but also the Cross of Christ. The cross was hewn in pieces, one portion only remaining at Jerusalem, where it continued to be shown to pilgrims. A further certain historical fact is, that on the spot thus said to have been discovered, and on which we now stand, a sumptuously decorated church was erected (consecrated in 336), consisting of a building over the [supposed Holy Sepulchre, and of the basilica dedicated to the sign of the Cross. The Church of the Sepulchre, also called the Anastasis, because Christ here rose from the dead, consisted of a rotunda, in the middle of which was the sepulchre surrounded by statues of the twelve [apostles. The external form at least of this rotunda, which served as a model for the Sakhra mosque (p. 40), has been preserved. It was adjoined on the E. by an open space with colonnades (the extent of which cannot be determined), while farther to the E. stood the basilica, with courts on each side, three portals in front towards the E., and a forecourt and propylsea with flights of steps. A few fragments of the columns of the propylsea are still preserved. The appearance of the whole, from the E., as from the Mt of Olives for example, must have been very striking. The place of the finding of the cross was early distinguished from Golgotha, and there are conflicting statements as to the distance of each from the town.

In June, 614, the buildings were destroyed by the Persians. In 616-626 the church was rebuilt by Modestus, abbot of the monastery of Theodosius, with the aid of the Christians of Syria and Alexandria. It then consisted of three parts: the Church of the Resurrection (Anastasis), the Church of * the Cross (Martyrion), and the Church of Calvary; but in splendour it was inferior to its predecessor. From a description of the Church of the Sepulchre by Arculf in 670 it appears that an addition had been made to the holy places by tbe erection of a church of St. Mary on the S. side. In the time of Khalif Mâmûn (813-833) the patriarch Thomas of Jerusalem repaired and enlarged the dome over the Anastasis. In 936 and in 969 the church was partly destroyed by fire, and in 1010 the holy places were further damaged and desecrated by the Muslims. In 1055 a church again arose and in 1099 the Crusaders entered this church, or in particular the dome of the sepulchre, barefooted and with songs of praise. The existing buildings, however, appeared to the Crusaders much too insignificant, and they therefore erected a large church which embraced all the holy places and chapels. This was not done till the beginning of the 12th cent., as the Romanesque style of their buildings testifies. The church built by the Crusaders has been preserved down to the present time, but is not easily recognised as a building of that period in consequence of the numerous additions which it has received. To the E. of the rotunda of the sepulchre the Crusaders erected a church consisting of a nave and aisles, with three apses towards the E., beyond which, still farther to the E., already stood the chapel of St. Helena.

In 1187 the Arabs damaged these buildings. In 1192 the warriors of the Third Crusade were permitted to visit Jerusalem in sections, and the Bishop of Salisbury obtained from Saladin the concession that two Latin priests should be permitted specially to conduct the services in the Church of the Sepulchre. In 1244 the sepulchre was destroyed by the Kharezmians, but in 1310 a handsome church with numerous and superb altars had again arisen, to which in 1400 were added two domes. During the following centuries complaints were frequently made of the insecure condition of the dome of the sepulchre. At length, in 1719, it was restored, and a great part of the church rebuilt, notwithstanding much opposition on the part of the Muslims. In 1808 the church met with a great disaster. It was almost entirely "burned down, the dome fell in and crushed the chapel of the sepulchre, the columns cracked, and the lead from the roof flowed into the interior. Little was saved except the E. part of the building. The Greeks now contrived to secure to themselves the principal right to the buildings, and they, together with the Armenians, contributed most largely to the erection of the new church of 1810, which was designed by a certain Komnenos Kalfa of Mitylene (p. 65). Many traces of the original church are, however, still distinguishable.

The Church of the Sepulchre (Arab. Kenîset el-Kiyameh) is generally closed from 10.30 a.m. to 3 p.m., but by paying a bakhshîsh of 1 fr. to the Muslim custodian the visitor will be allowed to remain in tbe building after 10.30 o'clock. An opera-glass and a light are indispensable. A bright day should be chosen, as many parts of the building are very dark. — Muslim guards, appointed by the Turkish government, sit in the vestibule for the purpose of reserving order among the Christian pilgrims and of keeping the keys. The office of custodian is hereditary in a Jerusalem family. ■— A large model of the Church of the Sepulchre by Dr. Schick, a Ger man architect, which gives a comprehensive idea of the whole of the buildings connected with it, is to be seen at his- house (p. 83).

The chief facade of the ohurch is now on the S. side of the open space in front of the present portal dates from the period of the Crusades. It is paved with large yellowish slabs of stone, and is always occupied by traders and beggars.

This Quadrangle (PI. a), or fore-court, which is not quite level, lies 3 1/2 steps below the street. To the right and left of the steps are columns built into the adjoining buildings, but that on the left (W.) only is well preserved, and even supports part of an arch closing the street leading to the W. Here stood a kind of Porch, as is rendered farther obvious by the remains of bases of columns still to be seen on the ground.

The quadrangle is bounded by chapels of no great importance. Entering by the most southern door on the right, and passing the kitchen and pilgrims' chambers of the Greeks, we ascend by eighteen steps to the so-called Church of the Apostles with the altar of Melchizedek (PI. 1) at the end of a long passage. Further to the N. , over the Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross (PI. 38), is the Chapel of the Sacrifice. A round hollow in the centre of the pavement indicates the spot where Abraham was on the point of sacrificing Isaac (comp. p. 72). The tradition in this form is comparatively recent, but the scene of Abraham's sacrifice was placed in this neighbourhood as early as the year 600.

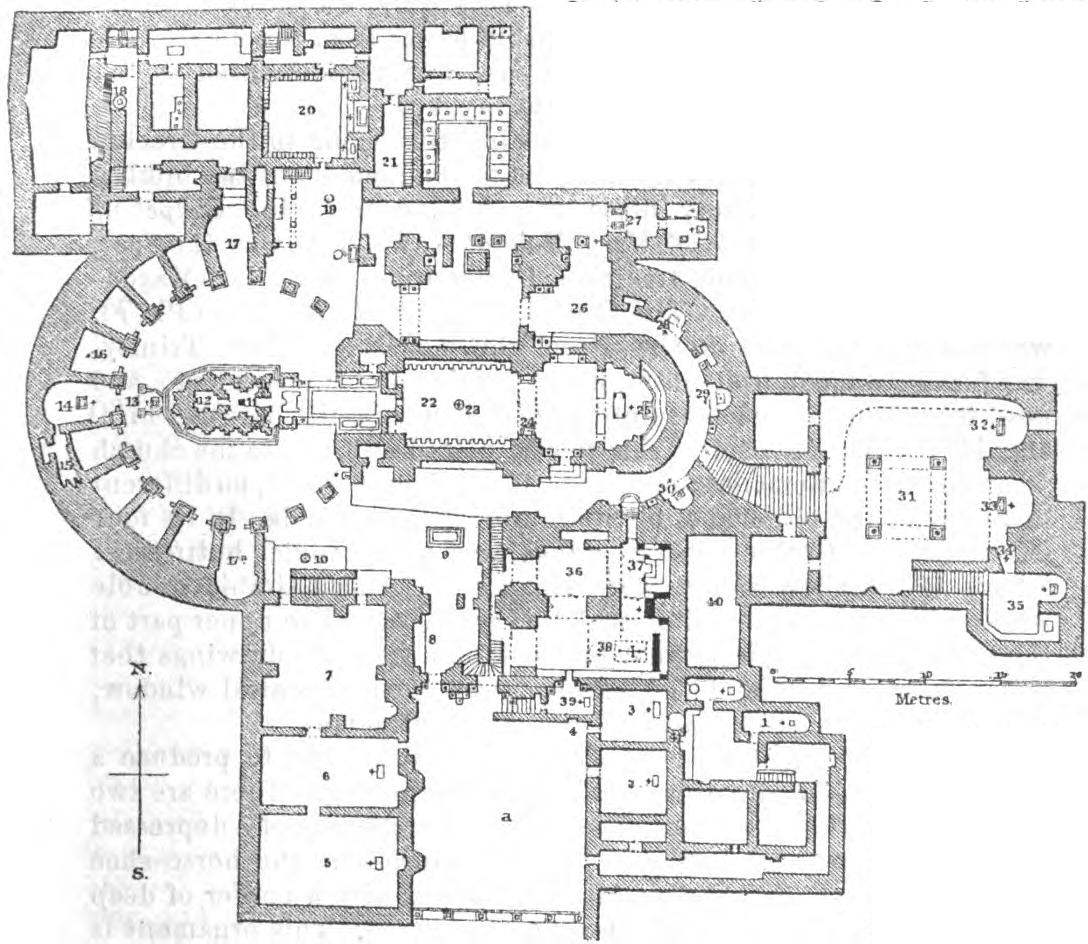

1. Chapel of Melchizedek. 2. Armenian Chapel. 3. Coptic Chapel. 4. Chapel of St. Mary of Egypt. 5. Greek Chapel of St. James. 6. ChapeI of Mary Magdalen. 7. Chapel of the Forty Martyrs. 8. Post of the Muslim custodians. 9. Stone of Anointment. 10. Place from which the women witnessed the Anointment, 1l. Angels' Chapel. 12. Chapel of the Sepulchre. 13. Chapel of the Copts. 14. Chapel of the Syrians. 15. Chamber in the rock. 16. Passage to the Coptic Monastery. 17. Passage to the Cistern. 18. Cistern. 19. Antechamber of next chapel. 20. Chapel of the Apparition. 21. Latin Sacristy. 22. Catholicon. 23. 'Centre of the World-1. 24. First seat of the Patriarch of Jerusalem. 25. Second seat. 26. Aisle of the Church of the Crusaders. 27. Chapel (Prison of Christ). 28. Chapel of St. Longinus. 29. Chapel of the Parting of the Raiment. 30. Chapel of the Derision. 31. Chapel of the Empress Helena. 32. Altar of the Penitent Thief. 33. Altar of the Empress. 34. Seat of the Empress. 35. Chapel of the Finding of the Cross. 36. Chapel of the Raising of the Cross. 37. Hole of the Cross. 38. Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross. 39. Chapel of the Agony. 40. Abyssinian Chapel.

We now return to the quadrangle, and enter the Armenian Chapel of St. James (PI. 2) with a crypt underneath, and the Coptic Chapel of the Archangel Michael (PI. 3). From the latter a corridor leads E. to the Abyssinian Chapel (PI, 40). In the corner of the quadrangle towards the N. a door next leads into the Greek Chapel of St. Mary of Egypt (PI. 4, below 39). This Mary, according to tradition, was driven away by some invisible power from the door of the Church of the Sepulchre in the year 374, but was succoured by the mother of Jesus whose image she had invoked.

The chapels to the W. of the quadrangle belong to the Greeks. The Chapel of St. James (PI. 5), sacred to the memory of the brother of Christ, is handsomely fitted up; behind it is the Chapel of St. Thecla. The Chapel of Mary Magdalen (PI. 6) marks the spot, where, according to Greek tradition, Christ appeared to Mary Magdalen for the third time. The Chapel of the Forty Martyrs (PI. 7), which originally stood on the site of the monastery of the Trinity, was formerly the burial-place of the patriarchs of Jerusalem , and now forms the lowest story of the Bell Tower (built between 1160 and 1180). The interior of this tower, placed adjacent to the church according to the Romanesque custom, is now incorporated, on different levels, with the old chapel of St. John and the rotunda. In its four sides are large Gothic window-arches, and at the angles buttresses. Above the window-arches were two rows of small Gothic double windows, the lower only of which is preserved. The upper part of the tower has been destroyed; but we know from old drawings that it consisted of several blind arcades, each with a central window, above which were pinnacles and an octagonal dome.

The S. Facade of the church can hardly be said to produce a pleasing effect, but its ornamentation is interesting. There are two portals, each with a window above it. The arches are of a depressed pointed character throughout, almost approaching the horse-shoe form. The arch over the portals is adorned with a border of deep dentels which fall perpendicularly on the curve. This ornament is said to be of late Roman origin. The door-frames are bordered with a series of elaborately executed waved lines. The columns adjoining the doors, probably taken from some ancient temple, are of marble: their capitals are Byzantine, but finely executed, and the pedestals are quite in the antique style. The columns have a common connecting beam, adorned with oak foliage. The space over the door to the left, originally covered with mosaic, is adorned in the Arabian style with a geometrical design of hexagons. Below the spaces above both doors are Basreliefs of great merit, which were probably executed in France in the second half of the 12th century.

The Basrelief over the Left Portal represents scenes from Bible history. In the first section to the left is the Raising of Lazarus in a vault : Christ with the Gospel, and Mary at his feet; Lazarus rises from the tomb; in the background spectators, some of them holding their noses! In the second section from the left, Mary beseeches Jesus to come for the sake of Lazarus. In the third section begins the representation of Christ's entry into Jerusalem. He first sends the disciples to fetch the ass; and two shepherds with sheep are introduced. The disciples bring the foal and spread out their garments ; in the background appears the Mt. of Olives. Then follows the Entry into Jerusalem. (The missing fragment, showing Christ upon the ass, is now in the Louvre.) The small figures which spread their garments in the way are very pleasing. A man is cutting palm- branches. A woman carries her child on her shoulder as they do in Egypt at the present day. In the foreground is a lame man with his crutch. The last section represents the Last Supper: John leans on Jesus' breast; Judas, on the outer side of the table, and separated from the other disciples, is receiving the sop. — The Basrelief over the Right Portal is an intricate mass of foliage, fruit, flowers, nude figures, birds, and other objects. In the middle is a centaur with his bow. The whole has an allegorical meaning : the animals below, which represent evil, conspire against goodness.

The second portal is walled up. In front of it begins a staircase which ascends from the outside into the Chapel of the Agony (p. 70). The staircase leads first to a small arcade, corresponding in character with the facade. The projecting structure in the N.E. corner of the quadrangle has also two stories , each formed by four large pointed arches, and has been converted into a chapel. — The tombstone of Philippe d'Aubigny, a Frankish knight, lies on the ground in front of the portals.

We now enter the Chubch of the Sepulchre itself by the large portal. In order to find our way, we must remember that the whole building extends from E. to W. As we enter from the S. we first reach an aisle of the church of the Crusaders. To the left we first observe the bench (PI, 8) of the Muslim custodians, who are generally regaling themselves with coffee and pipes, and to whom, if the church happens to be open, no bakhshish need be paid. For many centuries, and down to the beginning of the 19th, a heavy tax was levied here on every pilgrim. Passing the guard , we reach the large 'Stone of Anointment' (PI. 9), on which the body of Jesus is said to have lain when it was anointed by Nieodemus (St. John xix. 38-40"). The present stone, a reddish yellow marble slab, 8 1/2 ft long and 4 ft. broad, was placed here in 1808. Pilgrims were formerly in the habit of measuring the stone with a view to have their winding- sheets made of the same length.

Before the period of the Crusades a separate 'Church of St. Mary* rose over the place of Anointment, but a little to the S. of the present spot; when, however, the Franks enclosed all the holy places within one building, the stone of the anointment was removed to somewhere about its present site. The stone has often been changed, and has been in possession of numerous different religious communities in succession. In the 15th cent, it belonged to the Copts, in the 16th to the Georgians, from whom the Latins purchased permission for 5000 piastres to burn candles upon it, and afterwards to the Greeks. Over this stone Armenians, Latins, Greeks, and Copts are entitled to burn their lamps, and adjacent to it are candelabra of huge dimensions.

About 13 yards to the W. (left) of this point we reach a small, recently huilt enclosure round a stone (PI. 10) , which marks the spot where the women are said to have stood and witnessed the anointment. Beyond this, to the S., is the approach to the Armenian Chapel (PI. 2).

We now proceed to the right (N.) for a few paces, and arrive at the Rotunda of the Sepulchre, the principal part of the huilding, in the centre of which is the Sepulchre itself. The rotunda originally consisted of twelve large columns, which were probably divided into groups of three by piers placed between them. Above these were a drum and a dome, the latter being open at the top. The foundation pillars of the present day belonged to the old structure. Around the sacred chapel ran a double colonnade. The enclosing wall had three apses (still visible towards the N., W., and S. respectively; PI. 14, 17, 17a with mosaic pavement) with three altars, and another altar stood in front of the Sepulchre. The rotunda and dome were embellished with mosaics. Since the re-erection of the edifice in 1810 the dome has been supported by eighteen piers. These are connected overhead by arches, on which stands the drum with its dead windows, and on this the dome. The space between the external circular wall and the piers is divided by cross-vaulting into two stories, which were formerly continuous galleries, but are now divided into sections by transverse walls. The dome, which is open at the top, is 65 ft. in diameter. For a long time the old dome threatened to fall in, but an arrangement having been made between France, Russia, and the Porte for its restoration, the present structure was erected and completed in 1868. The pillars and most of the arches, as well as the drum had to be rebuilt. The dome is of iron and double. The ribs of the two domes are connected by iron braces. The inner side of the lower dome is lined with lead, the exterior of the upper dome is covered with boards, then with felt, and lastly with lead. Above the opening is a gilded iron screen, covered with glass, and surmounted by the gilt cross. The upper third of the lining of the dome is also decorated with gilt rays. Round the dome runs a gallery, commanding a view of the Sepulchre from above; adm. from the Greek monastery (p. 78).

In the centre of the rotunda, beneath the dome, is the Holy Sepulchre.

In the course of Constantine's search for the Holy Sepulchre a cavern in a rock was discovered, and a chapel was soon erected over the spot. In the time of the Crusaders the sanctuary of the Sepulchre was of a circular form and had a small round tower. At that period there were already two cavities, the outer of which was the angels' chapel while the inner contained the actual sepulchre. The building was surrounded with slabs of marble. A little later we hear of a polygonal huilding, artificially lighted within. After the destruction of the place in 1555 the tomb was uncovered, and an inscription with the name of Helena (?), and a piece of wood supposed to be a fragment of the cross were found. The Sepulchre was then redecorated, and three holes were made in the top of it for the escape of the smoke of the lamps. The whole building was restored in 1719. In 1808 the small tower of the chapel was destroyed by fire, the rest of the edifice being but slightly injured, notwithstanding which the whole enclosure was rebuilt in the debased style which it exhibits at the present day. The chapel is a hexagon, being 26 ft. long and 17 1/2 ft. wide, and has pilasters placed along the sides.

In front of the E. side there is a kind of antechamber provided, with two stone benches and large candelabra, where Oriental Christians are in the habit of removing their shoes, though we need not follow their example. We next enter the vestibule called the Angels' Chapel [PI. 11), 11 ft. long, and 10 ft. wide. Its walls are very thick, and incrusted with marble within and without. Steps on the right and left in the wall lead direct to the roof. In the centre of the chapel lies a stone set in marble, which is said to be that which the angel rolled away from the mouth of the sepulchre, and on which he afterwards sat. A fragment of this stone is said to be built into the altar on the place of the Crucifixion. As early as the 4th cent, such a stone is spoken of as having lain in front of the Sepulchre, but the stone appears to have been changed more than once in the course of the following centuries, and different fragments are sometimes mentioned. In this chapel burn fifteen lamps , five of which belong to the Greeks, five to the Latins, four to the Armenians, and one to the Copts.

Through a still lower door we next enter the Chapel of the Sepulchre (PI. 12), properly so called, which is only 6 1/2 ft. long, 6 ft. wide, and very low, holding not more than three or four persons at once. From the ceiling, which Is somewhat lofty and provided with a kind of chimney, are suspended forty-three precious lamps, of which four belong to the Copts, while the rest are equally divided among the other three sects. In the centre of the N. wall is a relief in white marble, representing the Saviour rising from the tomb. This relief belongs to the Greeks, that on the right of it to the Armenians, and that on the left to the Latins. On the inside of the door is the inscription in Greek : 'Lord remember thy servant, the imperial builder, Kalfa Komnenos of Mitylene, 1810' (p. 60). The roof of the chapel is borne by marble columns which stand on the inner walls of the cell. On the N. side, to the right of the entrance, is the marble tombstone. The shelf covered with marble is about 5 ft. long, 2ft. wide, and 3 ft. high. Mass is said here daily. The split marble slab is also used as an altar. We learn the character of the tomb of Christ from St. Luke (xxiii. 53 *). Originally the sepulchral grotto is said to have been here, and a cavity hewn in the rock is mentioned at a later period. What we have to picture to ourselves is a cavity, hollowed out to receive the body, and arched over (see p. oxi). Here, however, the whole surface was overlaid with marble as far back as the middle ages, and it would require very careful examination to ascertain whether a rock-tomb ever really existed here.

* `And he took it down, and wrapped it in linen, and laid it in a sepulchre that was hewn in stone, wherein never man before was laid*.

Immediately beyond the Sepulchre (to the W.) is a small chapel (PI. 13) which has belonged to the Copts since the 16th century.

We shall now make the circuit of the rotunda. Of the dark recesses around it, that immediately beyond the Copts' chapel is the most interesting. We first enter the plain Chapel of the Syrians, or Jacobites (PI. 14), at the back of which an old apse is seen. A door leads out of this ohapel to the left, towards the S., through a short and narrow passage, and down one step into a rocky chamber (PI. 15). By the walls are first observed two 'sunken tombs' (p. cxi), one of which is about 2 ft. and the other 3 1/2 ft. long, and both 3 ft. deep, having been probably destined for bones. In the rock to the S. are traces of 'shaft tombs', 5 1/2 ft- long, 1 1/2 ft. wide, and 2 1/2 ft. high. Since the 16th cent, tradition has placed the tombs of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus here, and researches have shown that we really have ancient Jewish tombs before us.

In the recess (PI. 16) to the N. of the Syrian chapel is a staircase ascending to the apartments of the Armenians. The bays are divided among the various sects ; the gallery over the two stories is also divided : one-third to the Armenians, two-thirds to the Latins.

The last recess (PI. 17), to the N. of the Sepulchre, is another of the original apses of the rotunda. Passing through it, we come to a passage leading between the dwellings of officials to a deep cistern (PI. 18), from which good fresh water may be obtained.

Returning to the rotunda, we turn to the N. into an antechamber (PI. 19) leading to the Latin Chapel of the Apparition. Tradition points this out as the spot where Jesus appeared to Mary Magdalen (John xx. 14, 15). The place where Christ stood is indicated by a marble ring in the centre, and that where Mary stood by another near the N. exit from the chamber. We now ascend by four round steps (to the left is the only organ in the church) to the Chapel of the Apparition (PI. 20), dating from the 14th cent., the principal chapel of the Latins. Legend relates that Christ appeared here to his mother after the resurrection. Immediately to the right (E.) of the entrance is an altar, behind which a fragment of the Column of the Scourging is preserved in a latticed niche in the wall, but it is not easy to see it, owing to the want of light. The history of the chapel is more closely connected with this precious relic than with the appearance of Christ to his mother, or with the legend that it occupies the site of the house of Joseph of Arimathea. The column was formerly shown in the house of Caiaphas, but was brought here at the time of the Crusaders. Judging from the narratives of different pilgrims, it must have frequently changed its size and colour, and a column of similar pretensions is shown at Rome also. There is a stick here which the pilgrims kiss after pushing it through a hole and touching the column with it. On the N. side, there is an entrance to the Latin Monastery, which is worth a visit. — The central altar is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, that in the N. corner to relics.

After quitting this chapel, we have on our left the entrance to the Latin Sacristy (PI. 21), where we are shown the sword, spurs, and cross of Godfrey de Bouillon, antiquities of doubtful genuineness . These are used in the ceremony of receiving knights into the Order of the Sepulchre, which has existed since the Crusades. The spurs are 8 in. long, and the sword 2 ft. 8 in. long, with a simple cruciform handle 5 in. long.

In again turning to the S., we have on our left the Church of the Crusaders, or Oreek Cathedral (also called Catholicon; PL 22), which was originally separate from the Church of the Sepulchre. This church has a semicircular apse with a retro-choir towards the E. The pointed windows and arcades, the clustered pillars, and the groined vaulting bear all the characteristics of the French transition style with the addition of Arabian details. The building was erected by an architect named Jourdain in 1140-49, but the simple and noble form of the choir was somewhat disfigured by the restoration of 1808.

Exactly opposite the door to the Sepulchre rises the large Arch of the Emperor, under which is the chief entrance to the church. The church is about 39 yds. in length and of varying width, and is lavishly embellished with gilding and painting. According to tradition, this building was erected above the garden of Joseph of Arimathea. Between the entrance and the choir is shown a kind of cup containing a flat ball, covered with network, which is said to occupy the Centre of the World (PI. 23), a fable of very early origin. On each side of the chapel is an episcopal throne. One seat to the N. is for the patriarch of Antioch, a second to the S. for the patriarch of Jerusalem (PI. 24), and another at the very back of the choir (PL 25). This choir with the high altar is shut off by a wall in the Greek fashion, and a so-called Iconoclaustrum thus formed, in which the treasures of the church are sometimes shown to personages of distinction.

Passing this partition wall, we proceed to the left and enter the aisle (PL 26) to the N. This aisle is formed towards the N. by two large pilasters, between which are still to be seen remains of the 'Seven Arches of the Virgin' which formerly stood here. Since the time of the Crusaders they have been completely built into the pillars ; but in the old building they formed one side of an open court, situated between the church of the sepulchre and the basilica. In the N.E. corner of this wall there is a dark chapel (Pl.,27). On the right of its entrance stands an altar, where through two round holes the Greeks show two impressions on the stone which are said to be footprints of Christ. These two holes form the so-called stocks in which the feet of Christ were put during the preparations for the Crucifixion (see the picture near the stone). This legend was unknown before the end of the 15th century. The chapel behind it, which also belongs to the Greeks, consists of three parts. As early as the beginning of the 12th cent, this was shown as the Prison of Christ, where he was bound while his cross was being prepared. The legend has since then been so variously embellished that it is

now difficult to trace the history of its different phases.

e return in the direction of the Catholicon, and walking round its choir we find in the outside wall to the left apses which belonged to the old choir of the Franks. Between the apses are chambers for clothes. The first apse is called the Chapel of St. Longinus (PI. 28). Longinus, whose name is mentioned in the 5th cent, for the first time, was the soldier who pierced Jesus' side; he had been blind of one eye, but when some of the water and blood spirted into his blind eye it recovered its sight. He thereupon repented and became a Christian. The chapel of this saint appears not to have existed earlier than the end of the 16th century. It belongs to the Greeks. The processions of the Latins do not stop in passing it, and do not acknowledge its sanctity. — The next chapel, quite at the back of the choir, is that of the Parting of the Raiment (PL 29), and belongs to the Armenians. It was shown as early as the 12th century. Between these two last-mentioned chapels is a door, through which the canons are said formerly to have entered the church.

Farther on is a staircase to the left the 29 steps of which lead us down to a chapel 65 ft. long, 42 ft. wide, situated 16 ft. below the level of the Sepulchre. This is the Chapel of St. Helena (PI. 31), and here once stood Constantine's basilica. In the 7th cent, a small sanctuary in the Byzantine style was erected here by Modestus, and the existing substructions date from this period. To the E. are three apses, and in the centre four cylindrical columns, which bear a dome. The latter has six side-windows, which give on the quadrangle of the Abyssinian monastery. The shafts of the columns are antique monoliths of reddish colour; their thickness, however, as well as the disproportionate size of the cubic capitals, give the whole a heavy appearance. The pointed vaulting dates from the time of the Crusaders (12th cent.). The chapel belongs to the Armenians. From the statements of mediaeval pilgrims, we learn that this chapel was regarded as the place where the cross was found. An upper and a lower section are mentioned for the first time in 1400. The altar in the N. apse (PI. 32) is dedicated to the memory of the penitent thief, and that in the middle (PI. 33) to the Empress Helena. To the right of the altar is shown a seat (PI. 34) in which the empress is said to have sat while the cross was being sought for; this tradition, however, is not older than the 15th century. In the 17th cent, the Armenian patriarch, who used to occupy this seat, complains of the way in which it was mutilated by pilgrims, and speaks of having been frequently obliged to renew it. Down to the time of Chateaubriand (1806) the old tradition was kept up that the columns of this chapel shed tears. Some explorers regard this chapel as part of the ancient city-moat.

Thirteen more steps descend to what is properly the Chapel of the Finding of the Cross (PI. 35) ; by the last three steps the natural rock makes its appearance. The (modern) chapel, which is really a cavern in the rock, is about 24 ft. long, nearly as wide, and 16 ft. high, and the floor is paved with stone. On its W. and S. sides are stone ledges. The place to the right belongs to the Greeks, and here is a marble slab in which a cross is beautifully inserted. On the left the Latins possess an altar, which was presented by Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria in 1857. A bronze statue of the Empress Helena of life-size represents her holding the cross. The pedestal is of the colour of the rock and rests on a foundation of green serpentine. On the wall at the back is a Latin inscription with the name of the founder.

We now retrace our steps to the top of the staircase and turning to the left, enter the Chapel of the Derision, or of the Crowning with Thorns (PI. 30), belonging to the Greeks, and without windows. About the middle of it stands an altar shaped like a box, which contains the so-called Column of Derision. This relic, which is first mentioned in 1384, has passed through many hands and frequently changed its size and colour since then. It is now a thick, light-grey fragment of stone, about 1 ft. high.

To the right of this chapel is a staircase, which ascends (to the S.) to the chapels on Golgotha, or Mt. Calvary. The pavement of these chapels lies 14 1/2 ft. above the level of the Church of the Sepulchre. It is, however, not yet ascertained whether this eminence consists of natural rock; no 'hill' is mentioned here till the time of the pilgrim of Bordeaux, after which there is a long silence on the subject. The spot which was supposed to be Mt. Calvary (perhaps the same as that which now bears the name) was enclosed in Constantine's basilica; subsequently, in the 7th cent., a special chapel was erected" over the holy spot, which, moreover, was afterwards alleged to be the scene of Abraham's trial of faith (comp. p. 62). At the time of the Crusaders the place, notwithstanding its height , was taken into the aisle of the church. After the fire of 1808 the chapels were enlarged, and the more eastern of the two entrances of the church, mentioned at p. 63, was filled up with a staircase from within. The first chapel on the N., the Chapel of the Raising of the Cross (PI. 36) , is separated from the second by two pillars only. It belongs to the Greeks, and is 42 ft. long and 14 1/2 ft wide. In the E. apse (PI. 37) is shown an opening lined with silver where the cross is said to have been inserted in the rock. The site of the crosses of the thieves is shown in the comers of the altarspace, each 5 ft. distant from the cross of Christ (doubtless much too near). They are first mentioned in the middle ages. Still more recent is the tradition that the cross of the penitent thief stood to the right (N.). About 4 l/2 ft. from the cross of Christ is the famous Cleft in the Rock (Matt, xxvii. 51) , now covered with a brass slide, under which is a grating of the same metal. When the slide is pushed aside, a cleft of about 6 inches in depth only is seen, the character of the rock being not easily distinguished (it is not marble). A deeper chasm in rock of a different colour was formerly shown. The cleft is said to reach to the centre of the earth ! — The chapel is sumptuously embellished with paintings and valuable mosaics. Behind the chapel is the refectory of the Greeks.

The adjoining chapel on the S. (PI. 38) belongs to the Latins, as does the altar of the 'Stabat' between the two chapels (13th station: the spot where Mary received the body of Christ on the descent from the cross). The chapel is fitted up in a much simpler style. Christ is said to have been nailed to the cross here. The spot is indicated by pieces of marble let into the pavement, and an altar-painting represents the scene. To the Latins also belongs the Chapel of St. Mary, or Chapel of the Agony (PI. 39), situated farther S., to which another staircase ascends outside the portal of the church (p. 63). It is only 13 ft. long and 9 1/2 ft. wide, but is richly decorated. The altar-piece represents Christ on the knees of his mother. Visitors may look into this chapel through a grating from Mt. Calvary.

We again descend the stairs. Beneath the Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross (PI. 38) lies the office of the Greek priests, and towards the N., under the Chapel of the Raising of the Cross, the Chapel of Adam, belonging to the Greeks. The chapel is not very old. A tradition, which was doubted at an early period, relates that Adam was buried here, that the blood of Christ flowed through the cleft in the rock on to his head, and that he was thus restored to life. It is also maintained that it is in consequence of this tradition that a skull is usually represented below the cross. The Oriental church places Melchizedek's tomb here. Eastwards, and a little to the right of the altar, behind a small brass door, a split in the rock is shown which corresponds with the one in the chapel above. Before reaching the W. door of the chapel, we observe, on the right and left, stone ledges on which originally were the monuments of the Frank kings of Jerusalem. When the Greeks took possession of these chapels after the fire in 1808, they removed the monuments, in order to evade the claims of the Latins to the chapels. The tombs were at that period outside the chapel, which was enlarged and the entrance from the space in front of the church of the Sepulchre walled up. On the ledge to the left was the Tombstone of Godfrey de Bouillon; the inscription, the import of whioh we know, was on a triangular prism which rested on four short columns. To the right (N.) was the similar Monument of Baldwin I. The Kharezmians

had already dispersed the bones of these kings.

During the Festival of Easter, the Church of the Sepulchre is crowded with pilgrims of every nationality, and there are enacted, both in the church and throughout the town , many disorderly scenes which produce a painful impression.

In former times, particularly during the regime of the Crusaders, the Latins used to represent the entry of Christ riding on an ass from Bethphage, but this was afterwards done in the interior of the church only. Palm and olive-branches were scattered about on the occasion, and to this day the Latins send to Gaza for palm branches, which are consecrated on Palm Sunday and distributed among the people. On Holy Thursday the Latins celebrate a grand mass and walk in procession round the chapel of the Sepulchre, after which the 'washing of feet' takes place at the door of the Sepulchre. The Greeks also perform the washing of feet, but their festival does not always fall on the same day as that of the Latins. Good Friday is also celebrated by the Franciscans with a mystery play, the proceedings terminating with the nailing of a figure to a cross. One of the most disgraceful spectacles is the so-called miracle of; the Holy Fire., in which the Latins participated down to the 16th cent.,but which has since been managed by the Greeks alone. On this occasion strangers are admitted to the galleries. The Greeks declare the miracle to date from the apostolic age, and it is mentioned by the monk Bernhard as early as the 9th century. Khalif Hakim was told that the priest used to besmear the wire by which the lamp was suspended over the sepulchre with resinous oil, and to set it on fire from the roof. The wild and noisy scene begins on Good Friday. The crowd passes the night in the church in order to secure places. On Easter Eve, about 2 p. m., a procession of the superior clergy moves round the Sepulchre , all lamps having been carefully extinguished in view of the crowd. Some members of the higher orders of the priesthood enter the chapel of the Sepulchre, while the priests pray and the people are in the utmost suspense. At length, the fire which has come down from heaven is pushed through a window of the Sepulchre, and there now follows an indescribable tumult, every one endeavouring to be the first to get his taper lighted. In a few seconds, the whole church is illuminated. This, however, never happens without fighting, and accidents generally occur owing to the crush. The sacred fire is carried home by the pilgrims. It is supposed to have the peculiarity of not burning human beings, and many of the faithful allow the flame to play upon their naked chests or other parts of their bodies. The spectators do not appear to take warning from the terrible catastrophe of 1834. On that occasion, there were upwards of 6000 persons in the church, when a riot suddenly broke out. The Turkish guards, thinking they were attacked, used their weapons against the pilgrims, and in the scuffle that followed about 300 pilgrims were killed. — Late on Easter Eve a solemn service is performed ; the pilgrims with torches shout Hallelujah, while the priests move round the Sepulchre singing hymns.

East Side of the Church of the Sepulchre. We follow the lane leading from the quadrangle of the church to the E., passing the entrance of the Muristan (p. 72) on the right, and the Greek Monastery of Abraham, with an interesting old cistern of great size, on the left. Adjoining, at the corner of the lane leading to the bazaar, is the Hospice of the Russian Palestine Society, beneath which are some ancient walls and an interesting ancient arch. We follow the Bazaar street to the W. Before the arcade is reached a path ascends to the left (W.), on which we pass several columns, the sole remains of the forecourt of the Basilica of Constantine (p. 59)

Our path across the roofs of ancient vaults turns to the N. and leads through a passage. Where the route turns to the W., a court is seen to the right, in which the dwellings of poor Latins are situated (called Dâr Ishâk Beg; here water is drawn from the cistern of St. Helena, see below). Near the end of the cul de sac we reach a column (right) and three doors, whence we obtain a view of the church from the E.

Through the door to the left we enter the court of the Abyssinian Monastery, in the centre of which rises a dome. Through this we look down into the chapel of St. Helena (p. 68). Around the court are several dwellings, but most of the members of the Abyssinian colony live in the miserable huts in the S.E. part of the court. Abyssinian monks read their Ethiopian prayers here, and point out, over the chapel of the finding of the cross, an olive-tree, of no great age, where Abraham found the goat entangled which he sacrificed instead of Isaac (that event having, as they say, taken place here). In the background a wall of the former refectory of the canons' residence becomes visible here. The Abyssinian chapel (PI. 40) is modern. A passage leads thence to the quadrangle of the Church of the Sepulchre (p. 61). The good-natured Abyssinians lead a most wretched life, and are more worthy of a donation than many of the other claimants.

Leaving the court of the Abyssinians, we have on our left the second of the above mentioned doors, a large iron portal which leads to the much handsomer Monastery of the Copts (Dêr es-Sultân). It has been partially restored and is fitted up in the European style as an episcopal residence, and contains a number of cells for the accommodation of pilgrims. The church, the foundations of which are old, is so arranged that the small congregation is placed on each side of the altar, which is enclosed by a railing. The porter of the monastery keeps the key of the Cistern of St. Helena. A winding staircase of 43 steps, some of which are in a bad condition, descends to the cistern. To the left, in descending, we observe an opening in the rock, by which a similar staircase, now walled up, descends from the N.; at the bottom is a handsome balustrade hewn in the rock. It is difficult to make out the full extent of the sheet of water ; but the whole reservoir is obviously hewn in the rock. Water is drawn hence for the use of the Latin poor-house, but its quality is not good. The cistern perhaps dates from a still earlier period than that of Constantine. The earliest of the pilgrims 'speaks of cisterns in this locality, probably meaning the one we are now visiting. (Fee for one person 3 pi., for a party more in proportion.)