Palestine and Syria: Handbook for Travelers

From the letters found at Tell el-'Amama (p. lviii), several of which were written from Urusalim by Prince Abdi-Khiba, we learn that about 1400 B.C. Jerusalem held a prominent place among the cities of S. Palestine. It was then subject to Egypt, and its princes were appointed by the Egyptian Pharaoh. — The town was named Jebus, and was distinguished as the chief stronghold of the Jebusites, when the Israelites captured it, which they did in the reign of David (2 Sam. v. 6-10). That king selected it for his residence and enlarged the fortress upon Mount Zion into the City of David.

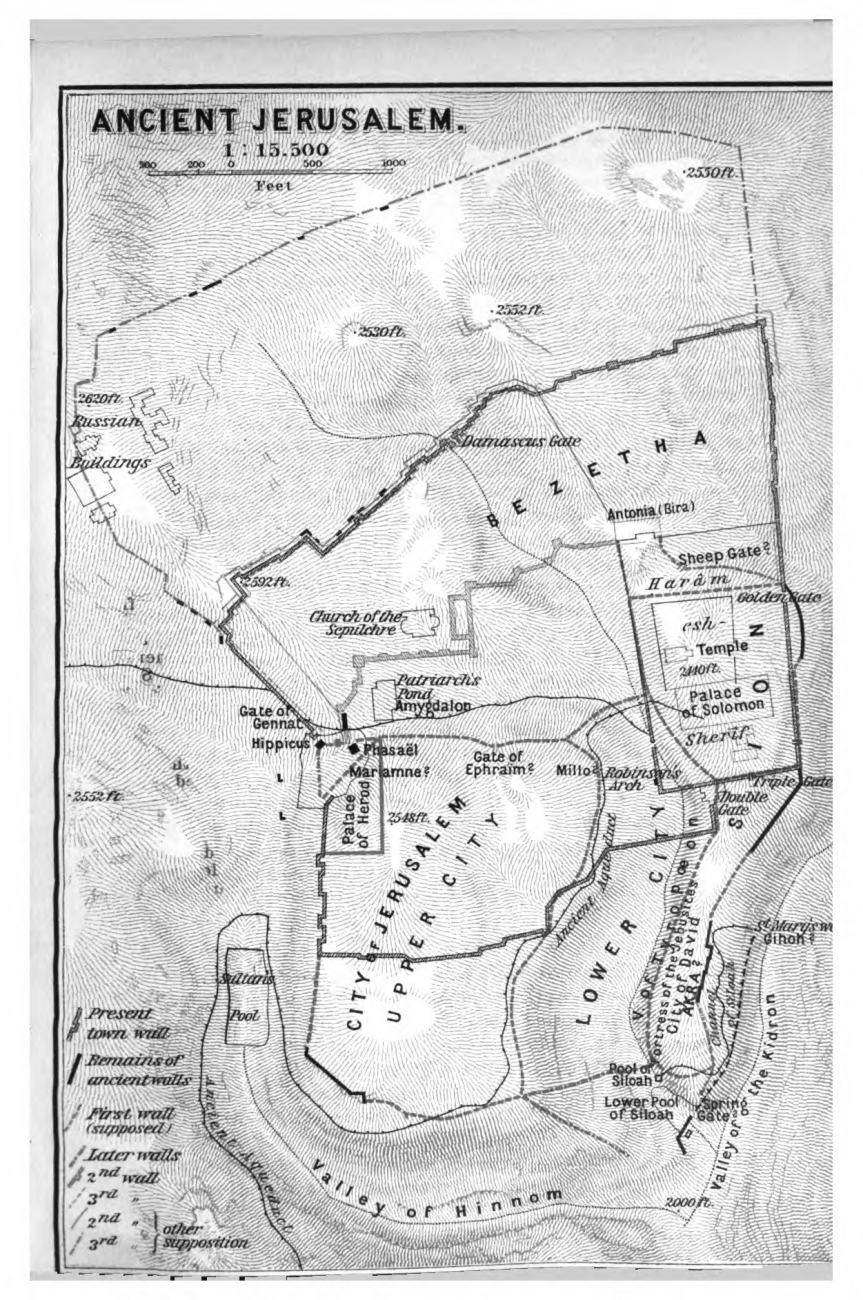

What then was the precise situation of this holy Mt. Zion? In order to answer this question, we must first examine the Topographical Character of the City (comp. the Plan, p. 22). The city was surrounded by deep valleys. Towards the E. lay the valley of the Kidron (afterwards called the valley of Jehoshaphat) , and on the W. and S. sides, the valley of Hinnom. These two principal valleys enclosed a plateau, the N. side of which bore the name of Bezetha, or 'place of olives. On the S. half of this plateau lay the city of Jerusalem , which was divided into different quarters by natural depressions of the soil. The chief of these natural boundaries was a small valley coming from the N., running at first S.S.E., and then due S., and separating two hills, of which that to the W. now rises 105 ft. above the precipitous E. hill. This valley, which is not mentioned in the Old Testament, was called by Josephus the Tyropoéon (cheese-makers' valley, or better, valley of dung).

On the S. terrace of the E. hill, where, to the S.E. of the present Harâm, lay the Ophel quarter, as well as on the other hill to the W. of the Tyropœon, extended the ancient Jerusalem as far as the brink of the valley. The city-wall crossed the Tyropcœon at its mouth far below. On the S. side of the W. hill (where there are now no houses) there was as early as David's time that part of the town which Josephus calls the Upper City.

Tradition places Zion and the City of David upon the W. hill, but the references in the Bible clearly show this to be an error. The Temple must certainly have stood upon the E. hill. But 'going up' to the Temple from the City of David is usually spoken of (2 Sam. xxiv. 18), so that the city cannot have stood upon the W. hill, which is higher than the hill of the Temple. Its site must therefore be looked for on the E. hill, below, i.e. to the S. of, the site of the Temple. Zion was the popular name for the hill of the Temple ; Jehovah dwelt on Zion (Joel iii. 21 ; Micah iv. 2; Is. viii. 18). Thus 'Zion' is frequently used as synonymous with the 'city of David' (2 Sam. v. 7; 1 Kings viii. I*), and is even poetically applied to Jerusalem itself ('daughter of Zion'). In passages of an earlier date the two are expressly distinguished from each other ('upon Mount Zion and on Jerusalem', Is. x. 12). — The name of Moriah occurs exceptionally in Gen. xxii. 2 and in 2 Chron. iii. 1 as a specifically religious appellation for the hill of the temple.

Tradition places Zion and the City of David upon the W. hill, but the references in the Bible clearly show this to be an error. The Temple must certainly have stood upon the E. hill. But 'going up' to the Temple from the City of David is usually spoken of (2 Sam. xxiv. 18), so that the city cannot have stood upon the W. hill, which is higher than the hill of the Temple. Its site must therefore be looked for on the E. hill, below, i.e. to the S. of, the site of the Temple. Zion was the popular name for the hill of the Temple ; Jehovah dwelt on Zion (Joel iii. 21 ; Micah iv. 2; Is. viii. 18). Thus 'Zion' is frequently used as synonymous with the 'city of David' (2 Sam. v. 7; 1 Kings viii. I*), and is even poetically applied to Jerusalem itself ('daughter of Zion'). In passages of an earlier date the two are expressly distinguished from each other ('upon Mount Zion and on Jerusalem', Is. x. 12). — The name of Moriah occurs exceptionally in Gen. xxii. 2 and in 2 Chron. iii. 1 as a specifically religious appellation for the hill of the temple.

* 'Then Solomon assembled the elders of Israel, unto king Solomon in Jerusalem, that they might bring up the ark of the covenant of the Lord out of the city of David, which is Zion'

Solomon began to beautify the city in a magnificent style, and above all, he erected on mount Zion a magnificent palace and sanctuary. In order, however, to procure a level surface for the foundation of such an edifice, it was necessary to lay massive substructions. The Temple of Solomon occupied the-N. part, the site of the upper terrace of the present day, on which the Dome of the Rock now stands (p. 39). (For farther details as to the history and site of the ancient Temple, see p. 36.) The royal palace rose immediately (Ezek. xlili. 7, 8) to the S. of the Temple, nearly on the site of the present mosque of Aksa, and extended thence to the E., where the rock forms a broad plateau. It consequently lay rather lower than the Temple, but higher than the City of David (see p. 22). "With this agrees the fact that Pharaoh's daughter 'came up' to it from the city of David (1 Kings ix. 24). This new palace was erected from Assyrian and Egyptian models, and sumptuously decorated. — Solomon also built Millo (1 Kings ix. 24 ; xi. 27), a kind of bastion or fort that perhaps completed the fortification of the city of David. Its position is quite uncertain. During his reign Jerusalem first became the headquarters of the Israelites, and it was probably then that this new city in the N. sprang up which he surrounded with fortifications.

The glory of Jerusalem as the central point of the united empire was, however, of brief duration ; after the division of the kingdom it became the capital of Judah only. So early as Rehoboam's reign, the city was compelled to surrender to the Egyptian king Shishak, on which occasion the Temple and palace were despoiled of part of their golden ornaments. About one hundred years later, under king Jehoram , the Temple was again plundered, the victors on this occasion being Arabian and Philistine tribes (2 Chron. xxi. 17). Sixty years later, Jehoash, the king of Israel, having defeated Amaziah of Judah, effected a wide breach in the wall of Jerusalem and entered the city in triumph (2 Kings xiv. 13, 14). Uzziah, the son of Amaziah, re-established the prosperity of Jerusalem. During this period, however, Jerusalem was visited by a great earthquake.

On the approach of Sennacherib the fortifications were repaired by Hezekiah (2 Chron. xxxii. 5), to whom also was due the great merit of providing Jerusalem with water. The solid chalky limestone on which the city stands contains little water. The only spring at Jerusalem was the fountain of Gihon on the E. slope of the Temple hill, outside the city-wall. By means of a subterranean channel Hezekiah conducted the water of the spring to the pool of Siloam, which lay within the walls. This spring being quite inadequate for the supply of the whole city, cisterns and reservoirs for the storage of rain-water were also constructed. The ponds on the W. side of the city were probably formed before the period of the captivity, as was also the large reservoir which still excites our admiration to the N. of the Temple plateau, and in the formation of which advantage was taken of a small valley, whose depth was at the same time destined to protect the site of the Temple on the N. side. A besieging army outside the city-walls generally suffered severely from want of water, as the issues of the conduits towards the country could be closed, while the city always possessed water in abundance. The valleys of Kidron and Hinnom must have ceased to be watered by streams at a very early period.

Hezekiah on the whole reigned prosperously, but the policy of his successors soon involved the city in ruin. In the reign of Jehoiachin, it was compelled to surrender at discretion to King Nebuchadnezzar. Again the Temple and the royal palace were pillaged, and a great numher of the citizens, including King Jehoiachin, the nobles , 7000 'men of might', 1000 craftsmen and their families were carried away captive to the East (2 Kings xxiv. 15 f.). Those who were left having made a hopeless attempt under Zedekiah to revolt against their conquerors , Jerusalem now had to sustain a long and terrible siege (1 year, 5 months, and 7 days). Pestilence and famine meanwhile ravaged the city. The besiegers approached with their roofed battering-rams, but the defence was a desperate one, and every inch of the ground was keenly contested, even after Zedekiah had fled down the Tyropoeon to the valley of the Jordan. The Babylonians now carried off all the treasures that still remained, the Temple of Solomon was burned to the ground, and Jerusalem reduced to the abject state of humiliation so beautifully described by the author of the Lamentations, particularly in chap. ii.

"When the Jews returned from captivity, they once more settled in Jerusalem, the actual rebuilding of which was the work of Nehemiah (p. Ixi). He re-fortified the city, retaining the foundations of the former walls, although these now enclosed a far larger space than was necessary for the reduced population.

The convulsions of the following centuries affected Jerusalem but slightly. The city opened its gates to Alexander, and after his death passed into the hands of the Ptolemies in the year 320. It was not till the time of Antiochus Epiphanes that it again became a theatre of bloodshed. On his return from Egypt, Antiochus plundered the Temple. Two years afterwards, he sent thither a chief collector of tribute, who destroyed Jerusalem, slew many of the inhabitants , and established himself in a stronghold in the centre of the city. This was the Akra, the site of which is disputed. As it is expressly stated to have stood on the site of the city of David (1 Mace. i. 33; ii. 31 ; vii. 31; xiv. 36), it must probably be located to the S. of the Temple. Some authorities place it, however, to the N.W. of the Temple.

Judas Maceabaeus (p. Ixi) recaptured the city, but not the Akra, and he fortified the hill of the Temple. But after the battle of Bethzachariah, Antiochus V. Eupator caused the walls of 'Zion' to be taken down (1 Mace. vi. 52) , in violation, it is said, of his sworn treaty. Jonathan, the Maccabaean, however, caused a stronger wall than ever to be erected (1 Mace. x. 11). He constructed another wall between the Akra, which was still occupied by a Syrian garrison, and the other parts of the city, whereby, at a later period, under Simon (B.C. 141), the citizens were enabled to reduce the garrison by famine. Under John Hyrcanus, the son of Simon, Jerusalem was again besieged by the Syrians (under Antiochus VII. Sidetes) in 134, and compelled to surrender by famine. The walls were demolished, but after the fall of Antiochus VII. Hyrcanus restored them, at the same time fortifying the Baria (see below) in the N.W. angle of the temple precincts, pulling town the Akra, and filling up the depression between its site and the Temple. Internal dissensions at length led to the intervention of the Romans. Pompey besieged the city, and again the attacks were concentrated against the Temple precincts, which, however, were defended on the N. side by large towers and a deep moat. Traces of this moat have been discovered. The only level approach by which the Temple platform could be reached was a bridge towards the W., for on this side at that period lay the Tyropœon, a valley of considerable depth. This bridge, which was afterwards destroyed, was probably situated near Wilson's Arch (p. 56). The quarter to the N. of the Temple, as well as the Gate of St. Stephen, do not appear to have existed at that period, and this is confirmed by Capt. Warren's excavations. The moat on the N. side was filled up by the Romans on a Sabbath ; they then entered the city by the embankment they had thrown up, and, exasperated by the obstinate resistance they had encountered, committed fearful ravages within the Temple precincts. In this struggle, no fewer than 12,000 Jews are said to have perished. To the great sorrow of the Jews, Pompey penetrated into their inmost sanctuary, but he left their treasures untouched. These were carried off by Crassus a few years later. Internal discord at Jerusalem next gave rise to the intervention of the Parthians, B. 0. 40.

In 37 Herod with the aid of the Romans captured the city after a gallant defence. The Jews had obstinately defended every point to the uttermost, and so infuriated were the victors that they gave orders for a general massacre. The part which had held out longest was the Baris. Herod, who now obtained the supreme power, embellished and fortified the city, and above all, he rebuilt the Temple , an event to which we shall hereafter revert (p. 37). He then refortifled the Baris also, as it commanded the Temple, and named it Antonia, in honour of his Roman patron. This castle was flanked with turrets externally, and was internally very spacious. He also built himself a sumptuous palace on the N.W. side of the upper city. This building is said to have contained a number of halls, peristyles, inner courts with lavish enrichments, and richly decorated columns. On the N. side of the royal palace stood three large towers of defence, named the Hippicus, Phasael, and Mariamne respectively (comp. p. 80). According to Roman custom, Herod also built a theatre at Jerusalem, and at the same time a town-hall (nearly on the site of the Mehkemeh, p. 65), and the Xystus, a space for gymnastic games sur rounded by colonnades. At this period Jerusalem with its numerous palaces and handsome edifices, the sumptuous Temple with its colonnades, and the lofty city-walls with their bastions, must have presented a very striking appearance. The wall of the old town had sixty towers, and that of the small suburb to the N. of it fourteen; but the populous city must have extended much farther to the N., and we must picture to ourselves in this direction numerous villas standing in gardens, some of which were probably very handsome buildings. Such was the character of the city in the time of Our Lord, but in the interior the streets, though paved , were somewhat narrow and crooked. The population must have been very crowded, especially on the occasion of festivals. The Soman governor is said on one occasion to have caused the paschal lambs to be counted, and to have found that they amounted to the vast number of 270,000, whence we may infer that the number of partakers was not less than 2,700,000. Although these figures, like many of the other statements of Josephus, are probably much exaggerated, they, at least, tend to show that the great national festival was attended by vast crowds.

After the death of Christ Agrippa I., at length, erected a wall which enclosed the whole of the N. suburb within the precincts of the city. This wall, which must have been of great extent and very strongly built to protect this most exposed quarter of Jerusalem, was composed of huge blocks of stone, and is said to have been defended by ninety towers. The strongest of these was the Psephinus tower at the N.W. angle, which was upwards of 100 ft. in height, and stood on the highest ground in the city (2572ft. above the sea-level ; comp. p. 80). From fear of incurring the displeasure of the Emperor Claudius, the wall was left unfinished, and it was afterwards completed in a less substantial style. As one of the chief points of controversy among the learned explorers of Jerusalem is the direction taken by the three walls, we may here give a short account of the subject.

The First Wall, that of David and Solomon, enclosed the old part of the town. Nehemiah's wall (p. 24) followed its course on the W., S., and E. sides. Beginning on the W. at the Furnace Tower (wich perhaps stood on the site later occupied by the tower of Hippicus), it followed the upper verge of the W. hill on the W. and S. sides, thus enclosing the modern suburb of Zion (comp. p. 22). On the S. side were probably two gates, leading to the S. from the upper city, viz. the Valley Gate, near the S.W. angle, and the Dung date, farther to the E. The wall was then carried in a double line across the Tyropœon, at the mouth of which was the 'Well Gate', probably identical with the 'Gate between two "Walls'. From the Pool of Siloam the wall ascended the hill northwards to the wall of the Temple. In the district of Ophel (p. 22) was the Water Gate, and farther to the N. was the 'Horse Gate' (a gate of the Temple). From the Hippicus the N. wall ran E. in an almost straight line to the Temple. Immediately to the S. of this N. wall stood the palace of Herod, the Xystus, and the bridge which crossed the Tyropœon to the Temple. In order to defend the upper part of the city, another wall ran down on the W. margin of the Tyropœon.

The Second Wall on the N., enclosing the N. suburb, also dates from the period of the early kings ; it was rebuilt by Nehemiah. At the point (on the W.) where it diverged from the first wall, Josephus placed the Gennat Gate (i.e. Garden Gate, perhaps the Corner Gate of the Bible), which has been discovered between the towers Hippicus and Phasael. Thence the wall made a curve to the N., interrupted (from to E.) by the Gate of Ephraim, the Old Gate, and the Fish Gate. At its N.E. angle it impinged upon the Temple precincts, where rose the Bira, a strong bastion called Boris by Josephus and afterwards named Antonia. This part of the N. wall was farther strengthened by the towers of Hananeel and Mea, the exact positions of which are still undetermined. On the direction assigned to this second wall depends the question of the genuineness of the 'Holy Sepulchre'. A number of authorities believe that the wall took much the same direction as the present town-wall, in which case it would have included what is now called the 'Holy Sepulchre', which, therefore, could not be genuine. Others, relying on the Russian excavations opposite the Muristan, hold that the wall and moat ran round the E. and S. sides of Golgotha.

"With regard to the situation'of the Third Wall, topographers likewise disagree. Those who hold that the 2nd wall corresponded to the present town-wall (see above) , must look for the 3rd wall far to the N. of it. The opinion now generally accepted is that this wall occupied nearly the same site as the present N. town-wall of Jerusalem ; there are still clear traces of an old moat round the present N. wall, and this view appears to be confirmed by the statement of the distances given by Josephus (4 stadia to the royal tombs , 7 stadia to the Scopus) , who , however , is not always accurate. But the question as to the situation of the second and third walls is by no means settled.

Ever since the land had become a Roman province a storm had begun to brood in the political atmosphere. At this time there were two antagonistic parties at Jerusalem : the fanatical Zealots under Eleazar, who advocated a desperate revolt against the Romans, and a more moderate party under the high priest Ananus. Florus, the Roman governor, in his undiscriminating rage, having caused many unoffending Jews to be put to death, a fearful insurrection broke out in the city. Herod Agrippa II. and his sister Berenice endeavoured to pacify the insurgents and to act as mediators, but were obliged to seek refuge in flight. The Zealots had already gained possession of the Temple precincts, and the castle of Antonia was now also occupied by them. After a terrible struggle the stronger faction of the Zealots succeeded in wresting the upper part of the city from their opponents, and even in capturing the castle of Herod which was garrisoned by 3000 men. The victors treated the captive Romans and their own countrymen with equal barbarity. Cestius Gallus, an incompetent Roman general, now besieged the city, but when he had almost achieved success he gave up the siege, and withdrew towards the N. to Gibeon. His camp was there attacked hy the Jews and his army dispersed. This victory so elated the Jews that they imagined they could now entirely shake off the Roman yoke. The newly constituted council at Jerusalem, composed of Zealots, accordingly proceeded to organise an insurrection throughout the whole of Palestine. The Romans despatched their able general Vespasian with 60,000 men to Palestine. This army first quelled the insurrection in Galilee (A. D. 67). Within Jerusalem itself bands of robbers took possession of the Temple, and, when besieged by the high-priest Ananus, summoned to their aid the Idumæans (Edomltes), the ancient hereditary enemies of the Jews. To these auxiliaries the gates were thrown open, and with their aid the moderate party with Ananus, its leader, annihilated. The adherents of the party were proscribed, and no fewer than 12,000 persons of noble family are said to have perished on this occasion.

It was not till Vespasian had conquered a great part of Palestine that he advanced with his army against Jerusalem ; but events at Rome compelled him to entrust the continuation of the campaign to his son Titus. When the latter approached Jerusalem there were no fewer than four parties within its walls. The Zealots under John of Giscala occupied the castle of Antonia and the court of the Gentiles, while the robber party under Simon of Gerasa held the upper part of the city; Eleazar's party was in possession of the inner Temple and the court of the Jews; and, lastly, the moderate party was also established in the upper part of the city. At the beginning of April, A. D. 70, Titus had assembled six legions (each of about 6000 men) in the environs of Jerusalem. He posted the main body of his forces to the N. and N.W. of the city, while one legion occupied the Mt. of Olives. The Jews in vain attempted a sally against the latter. Within the city John of Giscala succeeded in driving Eleazar from the inner precincts of the Temple. On 23rd April the besieging engines were brought up to the W. wall of the new town (near the present Jaffa Gate); on 7th May the Romans effected their entrance into the new town. Five days afterwards Titus endeavoured to storm the second wall, but was repulsed; but three days later he succeeded in taking it, and he then caused the whole N. side of the wall to be demolished. He now sent Josephus, who was present in his camp, to summon the Jews to surrender, but in vain. A famine soon set in, and those of the besieged who endeavoured to escape from it, and from the savage barbarities of Simon, were crucified by the Romans. The besiegers now began to erect walls of attack, but the Jews succeeded in partially destroying them. Titus thereupon caused the city-wall, 33 stadia in length, to be surrounded by a wall of 39 stadia in length. Now that the city was completely surrounded, the severity of the famine was greatly aggravated, and the bodies of the dead were thrown over the walls by the besieged. Again the battering rams were brought into requisition, and, at length, on the night of 5th July, the castle was stormed. A fierce contest took place around the gates of the Temple, but the Jews still retained possession of them. By degrees the colonnades of the Temple were burned down; yet every foot of the ground was desperately contested. At last, on 10th August, a Roman soldier is said to have flung a firebrand into the Temple, contrary to the express commands of Titus. The whole building was burned to the ground , and the soldiers slew all who came within their reach. A body of Zealots, however, contrived to force their passage to the upper part of the city. Negociations again took place, while the lower part of the town was in flames ; but still the upper part obstinately resisted, and it was not till 7th September that it was burned down. Jerusalem was now a heap of ruins ; those of the surviving citizens who had fought against the Romans were executed, and the rest sold as slaves.

At length, in 130, the Emperor Hadrian (117-138), who was noted for his love of building , erected a town on the site of the Holy City, which he named Aelia Capitolina, or simply Aelia. Hadrian also rebuilt the walls, which followed the course of the old walls in the main, but were narrower towards the S., so as to exclude the greater part of the W. hill and of Ophel. Once more the fury of the Jews blazed forth under Bar Cochba, but after that period the history of the city was for centuries buried in profound obscurity , and the Jews were prohibited under severe penalties from setting foot within its walls.

With the recognition of Christianity as the religion of the state a new era begins in the history of the city. Constantine permitted the Jews to return to Jerusalem , and once more they made an attempt to take up arms against the Romans (339). The Emperor Julian the Apostate favoured them in preference to the Christians, and even permitted them to rebuild their Temple, but they made a feeble attempt only to avail themselves of this permission. At a later period they were again excluded from the city.

As an episcopal see, Jerusalem was subordinate to Cæsarea, and it was only after numerous disputes that an independent patriarchate for Palestine was established at Jerusalem by the Council of Chalædon in 451. Pilgrimages to Jerusalem soonbecame very frequent, and the Emperor Justinian is said to have erected a hospice for strangers, as well as several churches and monasteries in and around Jerusalem. In 570 there were in Jerusalem hospices with 3000 beds. Pope Gregory the Great and several of the western states likewise erected buildings for the accommodation of pilgrims, and, at the same time, a thriving trade in relics of every description began to be carried on at Jerusalem.

In 614 Jerusalem was taken by the Persians and the churches destroyed, but it was soon afterwards restored, chiefly with the aid pf the Egyptians. In 628 the Byzantine emperor Heraclius again conquered Syria, A few years later an Arabian army under Abu 'Ubeida marched against Jerusalem, which was garrisoned by 12,000 Greeks. The besieged defended themselves gallantly, but the Khalîf 'Omar himself came to the aid of his general and captured the city in 637. The inhabitants, who are said to have numbered 50,000, were treated with clemency, and permitted to remain in the city on payment of a poll-tax. The Khalîf Harûn er-Rashîd is even said to have sent the keys of the Holy Sepulchre to Charlemagne. The Roman-German emperors sent regular contributions for the support of the pilgrims bound for Jerusalem, and it was only at a later period that the Christians began to be oppressed by the Muslims. The town was named by the Arabs Bêt el-Makdis ('house of the sanctuary'), or simply El-Kuds ('the sanctuary').

In 969 Jerusalem fell into possession of the Egyptian Fatimites; in the 2nd half of the 11th cent, it was involved in the conflicts of the Turcomans. Under their rule the Christians were sorely oppressed. Money was extorted from the pilgrims, and savage bands of Ortokides, or Turkish robbers, sometimes penetrated into the churches of Jerusalem and maltreated the Christians during worship. These oppressions, with other causes, brought about the First Crusade. The city was in the hands of Iftikhâr ed-Dauleh, a dependent of Egypt, when the army of the Crusaders advanced to the walls of Jerusalem on 7th June, 1099. The besiegers suffered much from hunger and thirst, and, at first, could effect nothing, as they were without the necessary engines of attack. Robert of Normandy and Robert of Flanders were posted on the N. side; on the W. Godfrey and Tancred; on the W., too, but more especially on the S., was Raymond of Toulouse. When the engines at length were erected, Godfrey attacked the city, chiefly from the S. and E. ; Tancred assaulted it on the N., and the Damascus Gate was opened to him from within. On 15th July the Gate of Zion was also opened, and the Franks entered the city. They slew most of the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants , and converted the mosques into churches. We shall afterwards have occasion to speak of the churches erected by the Crusaders during the 88 years of their sway at Jerusalem.

In 1187 (2nd Oct.) Saladin captured the city, treating the Christians, many of whom had fled to the surrounding villages, with great leniency. Three years later, when Jerusalem was again threatened by the Franks (Third Crusade), Saladin caused the city to be strongly fortified. In 1219, however, Sultan Melik el-Mu'azzam of Damascus caused most of these works to be demolished, as he feared that the Franks might again capture the city and establish themselves there permanently. In 1229 Jerusalem was surrendered to the Emperor Frederick II., on condition that the walls should not be rebuilt, but this stipulation was disregarded by the Franks. In 1239 the city was taken by the Emir David of Kerak, but four years later was again given up to the Christians by treaty. In 1244 the Kharezmians took the place by storm, and it soon fell under the supremacy of the Eyyubides. Since that period Jerusalem has been a Muslim city. In 1517 it fell into the hands of the Osmans. In 1800 Napoleon planned the capture of Jerusalem, but gave up his intention. In 1825 the inhabitants revolted against the pasha on account of the severity of the taxation, and the city was in consequence bombarded by the Turks for a time ; but a compromise of the disputes was effected. In 1831 Jerusalem submitted to Mohammed 'Ali, Pasha of Egypt, without much resistance; in 1834 a revolt of the Beduins was quelled ; and in 1840 Jerusalem again came into possession of the Sultan 'Abdul-Mejid.