8th August, to Rock Creek.

Resuming, through air refrigerated by rain, our now weary way, we reached at 6 A.M. a favorite camping-ground, the “ Big Nemehaw” Creek, which, like its lesser neighbor, flows after rain into the Missouri River, viâ Turkey Creek, the Big Blue, and the Kansas. It is a fine bottom of rich black soil, whose green woods at that early hour were wet with heavy dew, and scattered over the surface lay pebbles and blocks of quartz and porphyritic granites. “Richland,” a town mentioned in guide-books, having disappeared, we drove for breakfast to Seneca, a city consisting of a few shanties, mostly garnished with tall square lumber fronts, ineffectually, especially when the houses stand one by one, masking the diminutiveness of the buildings behind them. The land, probably in prospect of a Pacific Railroad, fetched the exaggerated price of $20 an acre, and already a lawyer has “hung out his shingle” there. :

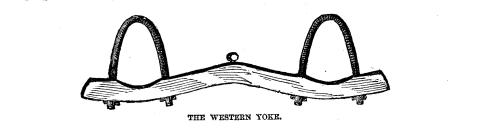

Refreshed by breakfast and the intoxicating air, brisk as a bottle of veuve Clicequot—it is this that gives one the “ prairie fever” —we bade glad adieu to Seneca, and prepared for another long stretch of twenty-four hours. That day’s chief study was of wagons, those ships of the great American Sahara which, gathering in fleets at certain seasons, conduct the traffic between the eastern and the western shores of a waste which is every where like a sea, and which presently will become salt. The white-topped wain—banished by railways from Pennsylvania, where, drawn by the “Conestoga horse,” it once formed a marked feature in the landscape—has found a home in the Far West. They are not unpicturesque from afar, these long-winding trains, in early morning like lines of white cranes trooping slowly over the prairie, or in more mysterious evening resembling dim sails crossing a rolling sea. The vehicles are more simple than our Cape wagons—huge beds like punts mounted on solid wheels, with logs for brakes, and contrasting strongly with the emerald plain, white tilts of twilled cotton or osnaburg, supported by substantial oaken or hickory bows. The wain is literally a “prairie ship:” its body is often used as a ferry, and when hides are unprocurable the covering is thus converted into a “bull boat.” ‘Two stakes driven into the ground, to mark the length, are connected by a longitudinal keel and ribs of willow rods; cross-sticks are tied with thongs to prevent ‘‘caving in,” and the canvas is strained over the frame-work. In this part of the country the wagon is unnecessarily heavy; made to carry 4000 lbs., it rarely carries 3000: westward I have seen many a load of 34 tons of 2000 lbs. each, and have heard of even 6 tons. The wheels are of northern white oak, well seasoned under pain of perpetual repairs, the best material, “ bow-dark” Osage orange-wood (bois d’arc or Maclura aurantiaca), which shrinks but little, being rarely procurable about Concord and Troy, the great centres of wagon manufacture. The neap or tongue (pole) is jointed where it enters the hounds, or these will be broken by the heavy jolts; and the perch is often made movable, so that after accidents a temporary conveyance can be made out of the débris. A long covered wooden box hangs behind: on the road it carries fuel; at the halt it becomes a trough, being preferred to nose-bags, which prevent the animals breathing comfortably ; and in the hut, where every part of the wagon is utilized, it acts as a chest for valuables. A bucket swings beneath the vehicle, and it is generally provided with an extra chain for “coraling.” The teams vary in number from six to thirteen yoke; they are usually oxen, an ‘Old Country”’ prejudice operating against the use of cows.[1] The yoke, of pine or other light wood, is, as every where in the States, simple and effective, presenting a curious contrast to the uneasy and uncertain contrivances which still prevail in the antiquated Campagna and other classic parts of Europe. A heavy cross-piece, oak or cotton-wood, is beveled out in two places, and sometimes lined with sheet-lead, to fit the animals’ necks, which are held firm in bows of bent hickory passing through the yoke and pinned above. The several pairs of cattle are connected by strong chains and rings projecting from the under part of the wood-work.

The “ripper,” or driver, who is bound to the gold regions of Pike’s Peak, is a queer specimen of humanity. He usually hails from one of the old Atlantic cities—in fact, from settled America —and, like the civilized man generally, he betrays a remarkable aptitude for facile descent into savagery. His dress is a harlequinade, typical of his disposition. Eschewing the chimney-pot or stove-pipe tile of the bourgeois, he affects the “Kossuth,” an Anglo-American version of the sombrero, which converts felt into every shape and form, from the jaunty little head-covering of the modern sailor to the tall steeple-crown of the old Puritan. He disregards the trichotomy of St, Paul, and emulates St. Anthony and the American aborigines in the length of his locks, whose ends are curled inward, with a fascinating sausage-like roll not unlike the Cockney “aggrawator.” If a young hand, he is probably in the buckskin mania, which may pass into the squaw mania, a disease which knows no cure: the symptoms are, a leather coat and overalls to match, embroidered if possible, and finished along the arms and legs with fringes cut as long as possible, while a pair of gaudy moccasins, resplendent with red and blue porcelain beads, fits his feet tightly as silken hose. I have heard of coats worth $250, vests $100, and pants $150: indeed, the poorest of buckskin suits will cost $75, and if hard-worked it must be renewed every six months. The successful miner or the gambler—in these lands the word is confined to the profession—will add $10 gold buttons to the attractions of his attire. The older hand prefers to buckskin a “wamba” or round-about, a red or rainbow-colored flannel over a check cotton shirt; his lower garments, garnished a tergo with leather, are turned into Hessians by being thrust inside his cow-hide Wellingtons; and, when in riding gear, he wraps below each knee a fold of deer, antelope, or cow skin, with edges scalloped where they fall over the feet, and gartered tightly against thorns and stirrup thongs, thus effecting that graceful elephantine bulge of the lower leg for which “Jack ashore” is justly celebrated. Those who suffer from sore eyes wear huge green goggles, which give a crab-like air to the physiognomy, and those who can not procure them line the circumorbital region with lampblack, which is supposed to act like the surma or kohl of the Orient. A broad leather belt supports on the right a revolver, generally Colt’s Navy or medium size (when Indian fighting is expected, the large dragoon pistol is universally preferred); and on the left, in a plain black sheath, or sometimes in the more ornamental Spanish scabbard, is a buck-horn or ivory-handled bowie-knife. In the East the driver partially conceals his tools; he has no such affectation in the Far West: moreover, a glance through the wagon-awning shows guns and rifles stowed along the side. When driving he is armed with a mammoth fustigator, a system of plaited cow-hides cased with smooth leather; it is a knout or an Australian stock-whip, which, managed with both hands, makes the sturdiest ox curve and curl its back. If he trudges along an ox-team, he is a grim and grimy man, who delights to startle your animals with a whip-crack, and disdains to return a salutation: if his charge be a muleteer’s, you may expect more urbanity; he is then in the “upper-crust” of teamsters; he knows it, and demeans himself accordingly. He can do nothing without whisky, which he loves to call tarantula juice, strychnine, red-eye, corn juice, Jersey lightning, leg-stretcher, “tangle-leg,”[2] and many other hard and grotesque names; he chews tobacco like a horse; he becomes heavier “on the shoulder” or “on the shyoot,” as, with the course of empire, he makes his way westward; and he frequently indulges in a “spree,” which in these lands means four acts of drinking-bout, with a fifth of rough-and-tumble. Briefly, he is a post-wagon driver exaggerated.

Each train is accompanied by men on horse or mule back—oxen are not ridden after Cape fashion in these lands.[3] The equipment of the cavalier excited my curiosity, especially the saddle, which has been recommended by good authorities for military use. The coming days of fast warfare, when “heavies,” if not wholly banished to the limbo of things that were, will be used as mounted“ beef-eaters,” only for show, demand a saddle with as little weight as is consistent with strength, and one equally easy to the horse and the rider. In no branch of improvement, except in hat-making for the army, has so little been done as in saddles. The English military or hunting implement still endures without other merit than facility to the beast, and,in the man’s case, faculty of falling uninjured with his horse. Unless the rider be copper-lined and iron-limbed, it is little better in long marches than a rail for riding. As far as convenience is concerned, an Arab pad is preferable to Peat’s best. But the Californian saddle can not supply the deficiency, as will, I think, appear in the course of description.

The native Indian saddle is probably the degenerate offspring of the European pack-saddle: two short forks, composing the pommel and cantle, are nailed or lashed to a pair of narrow sideboards, and the rude tree is kept in shape by a green skin or hide allowed to shrink on. It remarkably resembles the Abyssinian, the Somal, and the Circassian saddle, which, like the “dug-out” canoe, is probably the primitive form instinctively invented by mankind. It is the sire of the civilized saddle, which in these lands varies with every region. The Texan is known by its circular seat; a string passed round the tree forms a ring: provided with flaps after the European style, it is considered easy and comfortable. The Californian is rather oval than circular; borrowed and improved from the Mexican, it has spread from the Pacific to the Atlantic slope of the Rocky Mountains, and the hardy and experienced mountaineer prefers it to all others: it much resembles the Hungarian, and in some points recalls to mind the old. French cavalry demipique. It is composed of a single tree of light strong wood, admitting a freer circulation of air to the horse’s spine —an immense advantage — and, being without iron, 1t can readily be taken to pieces, cleaned or mended, and refitted. ‘The tree is strengthened by a covering of raw-hide carefully sewed on; it rests upon a “sweat-leather,” a padded sheet covering the back, and it is finished off behind with an “anchero” of the same material protecting the loins. The pommel is high, like the crutch of a woman’s saddle, rendering impossible, under pain of barking the knuckles, that rule of good riding which directs the cavalier to keep his hands low. It prevents the inexperienced horseman being thrown forward, and enables him to “hold on” when likely to be dismounted; in the case of a good rider, its only use is to attach the lariat, riata, or lasso. The great merit of this “unicorn” saddle is its girthing: with the English system, the strain of a wild bull or of a mustang “bucker” would soon dislodge the riding gear. The “sincho” is an elastic horsehair cingle, five to six inches wide, connected with “lariat straps,” strong thongs passing round the pommel and cantle; it is girthed well back from the horse’s shoulder, and can be drawn till the animal suffers pain: instead of buckle, the long terminating strap is hitched two or three times through an iron ring. The whole saddle is covered with a machila, here usually pronounced macheer, two pieces of thick leather handsomely and fancifully worked or stamped, joined by a running thong in the centre, and open to admit the pommel and cantle. If too long, it draws in the stirrup-leathers, and cramps the ankles of any but a bowlegged man. The machila is sometimes garnished with pockets, always with straps behind to secure a valise, and a cloak can be fastened over the pommel, giving purchase and protection to the knees. The rider sits erect, with the legs in a continuation of the body line, and the security of the balance-seat enables him to use his arms freely: the pose is that of the French schools in the last century, heels up and toes down. The advantages of this equipment are obvious; it is easier to horse and man probably than any yet invented. On the other hand, the quantity of leather renders it expensive: without silver or other ornaments, the price would vary from $25 at San Francisco to $50 at Great Salt Lake City, and the highly got-up rise to $250=£50 for a saddle! If the saddle-cloth slips out, and this is an accident which frequently occurs, the animal’s back will be galled. The stirrup-leathers can not be shortened or lengthened without dismounting, and without leggins the board-like leather macheer soon makes the mollets innocent of skin. The pommel is absolutely dangerous: during my short stay in the country I heard of two accidents, one fatal, caused by the rider being thrown forward on his fork. Finally, the long seat, which is obligatory, answers admirably with the Californian pacer or canterer, but with the high-trotting military horse it would inevitably lead—as has been proved before the European stirrup-leather was shortened—to hernias and other accidents.

To the stirrups I have but one serious objection—they can not be made to open in case of the horse falling; when inside the stiff leather macheer, they cramp the legs by bowing them ‘inward, but habit soon cures this. Instead of the light iron contrivances which before recovered play against the horse’s side, which freeze the feet in cold, and which toast them in hot weather, this stirrup is sensibly made of wood. In the Eastern States it is a lath bent somewhat in the shape of the dragoon form, and has too little weight; the Californian article is cut out of a solid block of wood, mountain mahogany being the best, then maple, and lastly the softer pine and cotton-wood. In some parts of the country it is made so narrow that only the toe fits in, and then the instep is liable to be bruised. For riding through bush and thorns, it is provided in front with zapateros or leathern curtains, secured to the straps above, and to the wood on both sides: they are curiously made, and the size, like that of the Turk’s lantern, denotes the owner’s fashionableness; dandies may be seen with ‘the pointed angles of their stirrup-guards dangling almost to the ground. The article was borrowed from Mexico—the land of character dresses. When riding through prickly chapparal, the leathers begin higher up, and protect the leg from the knee downward. I would not recommend this stirrup for Hyde Park, or even Brighton; but in India and other barbarous parts of the British empire, where, on a cold morning’s march, men and offcers may be seen with wisps of straw defending their feet from the iron, and on African journeys, where the bush is more than a match for any texture yet woven, it might, methinks, be advantageously used.

The same may be: said of the spurs, which, though cruel in appearance, are really more merciful than ours. The rowels have spikes about two inches long; in fact, are the shape and size of a small starfish; but they are never sharpened, and the tinkle near the animal’s sides serves to urge it on without a real application. The two little bell-like pendants of metal on each side of the rowel-hinge serve to increase the rattling, and when a poor rider is mounted upon a tricksy horse, they lock the rowels, which are driven into the sincho, and thus afford another point d’appui. If the rider’s legs be long enough, the spurs can be clinched under the pony’s belly. Like the Mexican, they can be made expensive: $25 a pair would be a common price.

The bridle is undoubtedly the worst part of the horse’s furntture. The bit is long, clumsy, and not less cruel than a Chifney. I have seen the Arab ring, which, with sufficient leverage, will break a horse’s jaw, and another, not unlike an East Indian invention, with a sharp triangle to press upon the animal’s palate, apparently for the purpose of causing it to rear and fall backward. Tt is the offspring of the Mexican manége, which was derived, through Spain, from the Moors.

Passing through Ash Point at 9 30 A.M., and halting for water at Uncle John’s Grocery, where hang-dog Indians, squatting, standing, and stalking about, showed that the forbidden luxury—essence of corn—was, despite regulations, not unprocurable there, we spanned the prairie to Guittard’s Station. This is a clump of board houses on the far side of a shady, well-wooded creek—the Vermilion, a tributary of the Big Blue River, so called from its red sandstone bottom, dotted with granitic and porphyritic boulders.

Our conductor had sprained his ankle, and the driver, being in plain English drunk, had dashed like a Phaeton over the “chuck-holes;” we willingly, therefore, halted at 11 30 A.M. for dinner. The host was a young Alsatian, who, with his mother and sister, had emigrated under the excitement of Californian fever, and had been stopped, by want of means, half way. The improvement upon the native was palpable: the house and kitchen were clean, the fences neat; the ham and eggs, the hot rolls and coffee, were fresh and good, and, although drought had killed the salad, we had abundance of peaches and cream, an offering of French to American taste which, in its simplicity, luxuriates in the curious mixture of lacteal with hydrocyanic acid.

At Guittard’s I saw, for the first time, the Pony Express rider arrive. In March, 1860, “the great dream of news transmitted from New York to San Francisco (more strictly speaking from St. Joseph to Placerville, California) in eight days was tested.” It appeared, in fact, under the form of an advertisement in the St. Louis “Republican,”[4] and threw at once into the shade the great Butterfield Mail, whose expedition had been the theme of universal praise. Very meritoriously has the contract been fulfilled. At the moment of writing (Nov., 1860), the distance between New York and San Francisco has been farther reduced by the advance of the electric telegraph—it proceeds at the rate of six miles a day—to Fort Kearney from the Mississippi and to Fort Churchill from the Pacific side. The merchant thus receives his advices in six days. The contract of the government with Messrs. Russell, Majors, and Co., to run the mail from St. Joseph to Great Salt Lake City, expired the 30th of November, and it was proposed to continue it only from Julesburg on the crossing of the South Platte, 480 miles west of St. Joseph. Mr. Russell, however, objected, and so did the Western States generally, to abbreviating the mail-service as contemplated by the Post-office Department. His spirit and energy met with supporters whose interest it was not to fall back on the times when a communication between New York and California could not be secured short of twenty-five or thirty days; and, aided by the newspapers, he obtained a renewal of his contract. The riders are mostly youths, mounted upon active and lithe Indian nags. They ride 100 miles at a time—about eight per hour—with four changes of horses, and return to their stations the next day: of their hardships and perils we shall hear more anon. The letters are carried in leathern bags, which are thrown about carelessly enough when the saddle is changed, and the average postage is $5=£1 per sheet.

Beyond Guittard’s the prairies bore a burnt-up aspect. Far as the eye could see the tintage was that of the Arabian Desert, sere and tawny as a jackal’s back. It was still, however, too early; October is the month for those prairie fires which have so frequently exercised the Western author's pen. Here, however, the grass is too short for the full development of the phenomenon, and beyond the Little Blue River there is hardly any risk. The fire can easily be stopped, ab initio, by blankets, or by simply rolling a barrel; the African plan of beating down with boughs might also be used in certain places; and when the conflagration has extended, travelers can take refuge in a little Zoar by burning the vegetation to windward. In Texas and Illinois, however, where the grass is tall and rank, and the roaring flames leap before the wind with the stride of maddened horses, the danger 1s imminent, and the spectacle must be one of awful sublimity.

In places where the land seems broken with bluffs, like an iron-bound coast, the skeleton of the earth becomes visible; the formation is a friable sandstone, overlying fossiliferous lime, which is based upon beds of shale. These undergrowths show themselves at the edges of the ground-waves and in the dwarf precipices, where the soil has been degraded by the action of water. The yellow-brown humus varies from forty to sixty feet deep in the most favored places, and erratic blocks of porphyry and various granites encumber the dry water-courses and surface drains. In the rare spots where water then lay, the herbage was still green, forming oases in the withering waste, and showing that irrigation is its principal, if not its only want.

Passing by Marysville, in old. maps Palmetto City, a county town which thrives by selling whisky to ruffians of all descriptions, we forded before sunset the “Big Blue,” a well-known tributary of the Kansas River. It is a pretty little stream, brisk and clear as crystal; about forty or fifty yards wide by 2°50 feet deep at the ford. The soil is sandy and solid, but the banks are too precipitous to be pleasant when a very drunken driver hangs on by the lines of four very weary mules. We then stretched once more over the “ divide’—the ground, generally rough or rolling, between the fork or junction of two streams, in fact, the Indian Doab—separating the Big Blue from its tributary the Little Blue. At 6 P.M. we changed our fagged animals for fresh, and the land of Kansas for Nebraska, at Cotton-wood Creek, a bottom where trees flourished, where the ground had been cleared for corn, and where we detected the prairie wolf watching for the poultry. The fur of our first coyote was light yellow-brown, with a tinge of red, the snout long and sharp, the tail bushy and hanging, the gait like a dog’s, and the manner expressive of extreme timidity; it is a far more cowardly animal than the larger white buffalo-wolf and the black wolf of the woods, which are also far from fierce. At Cotton-wood Station we took “‘on board” two way-passengers, “lady” and “gentleman,” who were drafted into the wagon containing the Judiciary. A weary drive over a rough and dusty road, through chill night air and clouds of musquetoes, which we were warned would accompany us to the Pacific slope of the Rocky Mountains, placed us about 10 P.M. at Rock, also called Turkey Creek—surely a misnomer; no turkey ever haunted so villainous a spot! Several passengers began to suffer from fever and nausea; in such travel the second night is usually the crisis, after which a man can endure for an indefinite time. The ‘ranch”’ was a nice place for invalids, especially for those of the softer sex. Upon the bedded floor of the foul “doggery” lay, in a seemingly promiscuous heap, men, women, children, lambs, and puppies, all fast in the arms of Morpheus, and many under the influence of a much jollier god. The employés, when aroused pretty roughly, blinked their eyes in the atmosphere of smoke and musquetoes, and declared that it had been “merry in hall” that night—the effects of which merriment had not passed off. After half an hour’s dispute about who should do the work, they produced cold scraps of mutton and a kind of bread which deserves a totally distinct generic name. ‘The strongest stomachs of the party made tea, and found some milk which was not more than one quarter flies. This succulent meal was followed by the usual douceur. On this road, however mean or wretched the fare, the stationkeeper, who is established by the proprietor of the line, never derogates by lowering his price.

[1]. According to Mormon rule, however, the full team consists of one wagon (12 ft. long, 3 ft. 4 in. wide, and 18 in. deep),two yoke of oxen, and two milch cows. The Saints have ever excelled in arrangements for travel by land and sea.

[2] For instance, “whisky is now tested. by the distance a man can walk after tasting it. The new liquor called ‘Tangle-leg’ is said to be made of diluted alcohol, nitric acid, pepper, and tobacco, and will upset a man at a distance of 400 yards from the demijohn.”

[3] Captain Marcy, in quoting Mr. Andersson’s remarks on ox-riding in Southwestern Africa, remarks that “a ring instead of a stick put through the cartilage of the animal’s nose would obviate the difficulty of managing it.” As in the case of the camel, a ring would soon be torn out by an obstinate beast: a stick resists.

[4] The following is the first advertisement:

“To San Francisco in eight days, by the Central Overland California and Pike's Peak Express Company.”

“The first courier of the ‘Pony Express’ will leave the Missouri River on Tuesday, April the 3d, at — o’clock P.M., and will run regularly weekly hereafter, carrying a letter mail only. ‘The point on the Missouri River will be in telegraphic communication with the East, and will be announced in due time.

“Telegraphic messages from all parts of the United States and Canada, in connection with the point of departure, will be received up to 5 o’clock P.M. of the day of leaving, and transmitted over the Placerville and St. Joseph Telegraph-wire to San Francisco and intermediate points by the connecting Express in eight days. The letter mail will be delivered in San Francisco in ten days from the departure of the Express. The Express passes through Forts Kearney, Laramie, and Bridger, Great Salt Lake City, Camp Floyd, Carson City, the Washoe Silver Mines, Placerville, and Sacramento. And letters for Oregon, Washington Territory, British Columbia, the Pacific Mexican Ports, Russian Possessions, Sandwich Islands, China, Japan, and India, will be mailed in San Francisco,

“Special messengers, bearers of letters, to connect with the Express of the 3d April, will receive communications for the Courier of that day at No. 481 Tenth Street, Washington City, up to 2 45 P.M. on Friday, March 30th; and in New York, at the office of J.B. Simpson, Room No. 8 Continental Bank Building, Nassau Street, up to 6 50 A.M. of 31st March. .

“Full particulars can be obtained on application at the above places, and from the Agents of the Company. W. H. RUSSELL, President.

“Leavenworth City, Kansas, March, 1860.

“Office, New York.—J. B. Simpson, Vice-President; Samuel and Allen, Agents, St. Louis, Mo.; H. J. Spaulding, Agent, Chicago.”