Past the Court-house and Scott’s Bluffs. August 13th.

At 8 A.M., after breaking our fast upon a tough antelope steak, and dawdling while the herdsman was riding wildly about in search of his runaway mules—an operation now to become of daily occurrence—we dashed over the Sandy Creek with an élan calculated to make timid passengers look “skeery,” and began to finish the rolling divide between the two forks. We crossed several arroyos and “criks” heading in the line of clay highlands to our left, a dwarf sierra which stretches from the northern to the southern branch of the Platte. The principal are Omaha Creek, more generally known as “Little Punkin,” [1] and Lawrence Fork. [2] The latter is a pretty bubbling stream, running over sand and stones washed down from the Court-house Ridge; it bifurcates above the ford, runs to the northeast through a prairie four to five miles broad, and swells the waters of old Father Platte: it derives its name from a Frenchman slaughtered by the Indians, murder being here, as in Central Africa, ever the principal source of nomenclature. The heads of both streams afford quantities of currants, red, black, and yellow, and cherry-sticks which are used for spears and pipe-stems.

After twelve miles’ drive we fronted the Court-house, the remarkable portal of a new region, and this new region teeming with wonders will now extend about 100 miles. It is the mauvaises terres, or Bad lands, a tract about 60 miles wide and 150 long, stretching in a direction from the northeast to the southwest, or from the Mankizitah (White-Earth) River, over the Niobrara (Eau qui court) and Loup Fork to the south banks of the Platte: its eastern limit is the mouth of the Keya Paha. The term is generally applied by the trader to any section of the prairie country where the roads are difficult, and by dint of an illname the Bad lands have come to be spoken of as a Golgotha, white with the bones of man and beast. American travelers, on the contrary, declare that near parts of the White River “some as beautiful valleys are to be found as any where in the Far West,” and that many places “abound in the most lovely and varied forms in endless variety, giving the most striking and pleasing effects of light and shade.” The formation is the pliocene and miocene tertiary, uncommonly rich in vertebrate remains: the - mauvaises terres are composed of nearly horizontal strata, and “though diversified by the effects of denuding agencies, and presenting in different portions striking characteristics, yet they are, as a whole, a great uniform surface, gradually rising toward the mountains, at the base of which they attain an elevation varying between 8000 and 5500 feet above the level of the sea.”

The Court-house, which had lately suffered from heavy rain, resembled any thing more than a court-house; that it did so in former days we may gather from the tales of many travelers, old Canadian voyageurs, who unanimously accounted it a fit place for Indian spooks, ghosts, and hobgoblins to meet in powwow, and to “count their coups” delivered in the flesh. The Court-house lies about eight miles from the river, and three from the road; in circumference it may be half a mile, and in height 300 feet; it is, however, gradually degrading, and the rains and snows of not many years will lay it level with the ground. The material is a rough conglomerate of hard marl; the mass is apparently the flank or shoulder of a range forming the southern buttress of the Platte, and which, being composed of softer stuff, has gradually melted away, leaving this remnant to rise in solitary grandeur above the plain. In books it is described as resembling a gigantic ruin, with a huge rotunda in front, windows in the sides, and remains of roofs and stages in its flanks: verily potent is the eye of imagination! To me it appeared in the shape of an irregular pyramid, whose courses were inclined at an ascendable angle of 35°, with a detached outwork composed of a perpendicular mass based upon a slope of 45°; in fact, it resembled the rugged earthworks of Sakkara, only it was far more rugged. According to the driver, the summit is a plane upon which a wagon can turn. My military companion remarked that it would make a fine natural fortress against Indians, and perhaps, in the old days of romance and Colonel Bonneville, it has served as a refuge for the harried fur-hunter. I saw it when set off by weather to advantage. A blazing sun rained fire upon its cream-colored surface—at 11 A.M. the glass showed 95° in the wagon—and it stood boldly out against a purple-black nimbus which overspread the southern skies, growling distant thunders, and flashing red threads of “chained lightning.”

I had finished a hasty sketch, when suddenly appeared to us a most interesting sight—-a neat ambulance,[3] followed by a fourgon and mounted soldiers, from which issued an officer in uniform, who advanced to greet Lieutenant Dana. The traveler was Captain, or rather Major Marcy, who was proceeding westward on leave of absence. After introduction, he remembered that his vehicle contained a compatriot of mine. The compatriot, whose length of facial hair at once told his race—for

“The larger the whisker, the greater the Tory”—

was a Mr. A _ British vice-consul at ***’s, Minnesota. Having lately tried his maiden hand upon buffalo, he naturally concluded that I could have no other but the same object. Pleasant estimate, forsooth, of a man’s brain, that it can find nothing in America worthy of its notice but bison-shooting! However, the supposition had a couleur locale. Every week the New York papers convey to the New World the interesting information that some distinguished Britisher has crossed the Atlantic and half crossed the States to enjoy the society of the “monarch of our prairies.” Americans consequently have learned to look upon this Albionic eccentricity as “the thing.” That unruly member the tongue was upon the point of putting in a something about the earnest, settled purpose of shooting a prairie-dog, when the reflection that it was hardly fair so far from home to “chaff” a compatriot evidently big with the paternity of a great exploit, with bit and bridle curbed it fast.

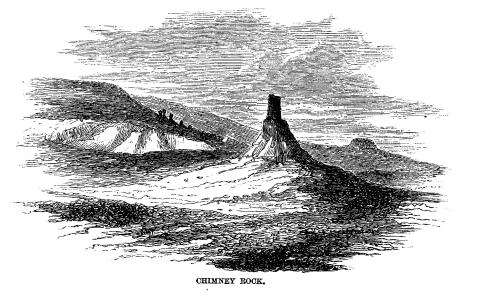

Shortly after “liquoring up” and shaking hands, we found ourselves once more in the valley of the Platte, where a lively green relieved eyes which still retained retina-pictures of the barren, Sindh-like divide. The road, as usual along the river-side, was rough and broken, and puffs of simoom raised the sand and dust in ponderous clouds. At 12 80 P.M. we nooned for an hour at a little hovel called a ranch, with the normal corral; and I took occasion to sketch the far-famed Chimney Rock. The name is not, as is that of the Court-house, a misnomer: one might almost expect to see smoke or steam jetting from the summit. Like most of these queer malformations, it was once the knuckle-end of the main chain which bounded the Platte Valley; the softer

adjacent strata of marl and earthy limestone were disintegrated by wind and weather, and the harder material, better resisting the action of air and water, has gradually assumed its present form. Chimney Rock lies two and a half miles from the south bank of the Platte. It is composed of a friable yellowish marl, yielding readily to the knife. The shape is a thin shaft, perpendicular and quasi conical. Viewed from the southeast it is not unlike a giant jack-boot based upon a high pyramidal mound, which, disposed in the natural slope, rests upon the plain. The neck of sandstone connecting it with the adjacent hills has been distributed by the floods around the base, leaving an ever-widening gap between. This “Pharos of the prairie sea” towered in former days 150 to 200 feet above the apex of its foundation,[4] and was a landmark visible for 40 to 50 miles: it is now barely 85 feet in height. It has often been struck by lightning; imber edax has gnawed much away, and the beginning of the end is already at hand. It is easy to ascend the pyramid; but, while Pompey’s Pillar, Peter Botte, and Ararat have all felt the Anglo-Scandinavian foot, no venturous scion of the race has yet trampled upon the top of Chimney Rock. Around the waist of the base runs a white band which sets off its height and relieves the uniform tint. The old sketches of this curious needle now necessarily appear exaggerated; moreover, those best known represent it as a column rising from a confused heap of boulders, thus conveying a completely false idea. Again the weather served us: nothing could be more picturesque than this lone pillar of pale rock lying against a huge black cloud, with the forked lightning playing over its devoted head.

After a frugal dinner of biscuit and cheese we remounted and pursued our way through airy fire, which presently changed from our usual pest—a light dust-laden breeze —into a Punjaubian dust-storm, up the valley of the Platte. We passed a ranch called “Robidoux’ Fort,” from the well-known Indian trader of that name; [5] it is now occupied by a Canadian or a French Creole, who, as usual with his race in these regions, has taken to himself a wife in the shape of a Sioux squaw, and has garnished his quiver with a multitude of whitey-reds. The driver pointed out the grave of a New Yorker who had vainly visited the prairies in search of a cure for consumption. As we advanced the storm increased to a tornado of north wind, blinding our cattle till it drove them off the road. The gale howled through the pass with all the violence of a khamsin, and it was followed by lightning and a few heavy drops of rain. The threatening weather caused a large party of emigrants to “fort themselves” in a corral near the base of Scott’s Bluffs.

The corral, a Spanish and Portuguese word, which, corrupted to “kraal,” has found its way through Southern Africa, signifies primarily a square or circular pen for cattle, which may be made of tree-trunks, stones, or any other convenient material. The corral of wagons is thus formed. The two foremost are brought near and parallel to each other, and are followed by the rest, disposed aslant, so that the near fore wheel of the hinder touches the off hind wheel of that preceding it, and vice versâ on the other side. The “tongues,” or poles, are turned outward, for conven1ence of yoking, when an attack is not expected, otherwise they are made to point inward, and the gaps are closed by ropes and yoke and spare chains. Thus a large oval is formed with a single opening fifteen to twenty yards across; some find it more convenient to leave an exit at both ends. In dangerous places the passages are secured at night either by cords or by wheeling round the near wagons; the cattle are driven in before sundown, especially when the area of the oval is large enough to enable them to graze, and the men sleep under their vehicles. In safer travel the tents are pitched outside the corral with their doors outward, and in front of these the camp-fires are lighted. The favorite spots with teamsters for corraling are the re-entering angles of deep streams, especially where these have high and precipitous banks, or the crests of abrupt hills and bluffs—the position for nighting usually chosen by the Australian traveler—where one or more sides of the encampment is safe from attack, and the others can be protected by a cross fire. As a rule Indians avoid attacking strong places; this, however, must not always be relied upon; in 1844 the Utah Indians attacked Uintah Fort, a trading-post belonging to M. A. Robidoux, then at St. Louis, slaughtered the men, and carried off the women. The corral is especially useful for two purposes: it enables the wagoners to yoke up with ease, and it secures them from the prairie traveler’s prime dread—the stampede. The Western savages are perfectly acquainted with the habits of animals, and in their marauding expeditions they instinctively adopt the system of the Bedouins, the Gallas, and the Somal. Providing themselves with rattles and other implements for making startling noises, they ride stealthily up close to the cattle, and then rush by like the whirlwind with a volley of horrid whoops and screams. When the “cavallard” flies in panic fear, the plunderers divide their party; some drive on the plunder, while the others form a rear-guard to keep off pursuers. The prairie-men provide for the danger by keeping their fleetest horses saddled, bridled, and ready to be mounted at a moment’s notice. When the animals have stampeded, the owners follow them, scatter the Indians, and drive, if possible, the madriña, or bell-mare, to the front of the herd, gradually turning her toward the camp, and slacking speed as the familiar objects come in sight. Horses and mules appear peculiarly timorous upon the prairies. A band of buffalo, a wolf, or even a deer, will sometimes stampede them; they run to great distances, and not unfrequently their owners fail to recover them.

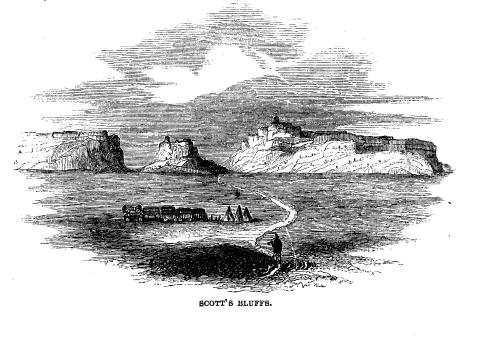

“Scott’s Bluffs,” situated 285 miles from Fort Kearney and 51 from Fort Laramie, was the last of the great marl formations which we saw on this line, and was of all by far the most curious. In the dull uniformity of the prairies, it is a striking and attractive object, far excelling the castled crag of Drachenfels or any of the beauties of romantic Rhine. From a distance of a day’s march it appears in the shape of a large blue mound, distinguished only by its dimensions from the detached fragments of hill around. As you approach within four or five miles, a massive medieval city gradually defines itself, clustering, with a wonderful fullness of detail, round a colossal fortress, and crowned with a royal castle. Buttress and barbican, bastion, demilune, and guard-house, tower, turret, and donjon-keep, all are there: in one place

parapets and battlements still stand upon the crumbling wall of a fortalice like the giant ruins of Château Gaillard, the “Beautiful Castle on the Rock;” and, that nothing may be wanting to the resemblance, the dashing rains and angry winds have cut the old line of road at its base into a regular moat with a semicircular sweep, which the mirage fills with a mimic river. Quaint figures develop themselves; guards and sentinels in dark armor keep watch and ward upon the slopes, the lion of Bastia crouches unmistakably overlooking the road; and as the shades of an artificial evening, caused by the dust-storm, close in, so weird is its aspect that one might almost expect to see some spectral horseman, with lance and pennant, go his rounds about the deserted streets, ruined buildings, and broken walls. At a nearer aspect again, the quaint illusion vanishes; the lines of masonry become yellow layers of boulder and pebble imbedded in a mass of stiff, tamped, bald marly clay; the curtains and angles change to the gashings of the rains of ages, and the warriors are metamorphosed into dwarf cedars and dense shrubs, scattered singly over the surface. Travelers have compared this glory of the mauvaises terres to Gibraltar, to the Capitol at Washington, to Stirling Castle. -I could think of nothing in its presence but the Arabs’ “City of Brass,” that mysterious abode of bewitched infidels, which often appears at a distance to the wayfarer toiling under the burning sun, but ever eludes his nearer search.

Scott’s Bluffs derive their name from an unfortunate fur-trader there put on shore in the olden time by his boat’s crew, who had a grudge against him: the wretch, in mortal sickness, crawled up the mound to die. The politer guide-books call them “Capitol Hills:” methinks the first name, with its dark associations, must be better pleasing to the genius loci. They are divided into three distinct masses. The largest, which may be 800 feet high, is on the right, or nearest the river. To its left lies an outwork, a huge, detached cylinder whose capping changes aspect from every direction; and still farther to the left is a second castle, now divided from, but once connected with the others. The whole affair is a spur springing from the main range, and closing upon the Platte so as to leave no room for a road.

After gratifying our curiosity we resumed our way. The route lay between the right-hand fortress and the outwork, through a degraded bed of softer marl, once doubtless part of the range. The sharp, sudden torrents which pour from the heights on both sides, and the draughty winds—Scott’s Bluffs are the permanent head-quarters of hurricanes—have cut up the ground into a labyrinth of jagged gulches steeply walled in. We dashed down the drains and pitch-holes with a violence which shook the nave-bands from our sturdy wheels.[6] Ascending, the driver showed a place where the skeleton of an “elephant” had been lately discovered. On the summit he pointed out, far over many a treeless hill and barren plain, the famous Black Hills and Laramie Peak, which has been compared to Ben Lomond, towering at a distance of eighty miles. The descent was abrupt, with sudden turns round the head of earth-cracks deepened to ravines by snow and rain; and one place showed the remains of a wagon and team which had lately come to grief. After galloping down a long slope of twelve miles, with ridgelets of sand and gravel somewhat raised above the bottom, which they cross on their way to the river, we found ourselves, at 5 30 P.M., once more in the valley of the Platte. I had intended to sketch the Bluffs more carefully from the station, but the western view proved to be disappointingly inferior to the eastern. After the usual hour’s delay we resumed our drive through alternate puffs of hot and cold wind, the contrast of which was not easy to explain. The sensation was as if Indians had been firing the prairies—an impossibility at this season, when whatever herbage there is is still green. It may here be mentioned that, although the meteorology of the earlier savans, namely, that the peculiar condition of the atmosphere known as the Indian summer [7] might be produced by the burning of the plain-vegetation, was not thought worthy of comment, their hypothesis is no longer considered trivial. The smoky canopy must produce a sensible effect upon the temperature of the season. “During a still night, when a cloud of this kind is overhead, no dew is produced; the heat which is radiated from the earth is reflected or absorbed, and radiated back again by the particles of soot, and the coating of the earth necessary to prevent the deposition of water in the form of dew or hoar-frost is prevented.” According to Professor Henry, of Washington, “it is highly probable that a portion of the smoke or fog-cloud produced by the burning of one of the Western prairies 1s carried entirely across the eastern portion of the continent to the ocean.”.

Presently we dashed over the Little Kiowa Creek, forded the Horse Creek, and, enveloped in a cloud of villainous musquetoes, entered at 8 30 P.M: the station in which we were to pass the night. It was tenanted by one Reynal, a French Creole—the son of an old soldier of the Grand Armée, who had settled at St. Louis —a companionable man, but an extortionate: he charged us a florin for every “drink” of his well-watered whisky. The house boasted of the usual squaw, a wrinkled old dame, who at once began to prepare supper, when we discreetly left the room. These hard-working but sorely ill-favored beings are accused of various horrors in cookery, such as grinding their pinole, or parched corn, in the impurest manner, kneading dough upon the floor, using their knives for any purpose whatever, and employing the same pot, unwashed, for boiling tea and tripe. In fact, they are about as clean as those Eastern pariah servants who make the knowing Anglo-Indian hold it an abomination to sit at meat with a new arrival or with an officer of a “home regiment.” The daughter was an unusually fascinating half-breed, with a pale face and Franco-American features. How comes it that here, as in Hindostan, the French half-caste is pretty, graceful, amiable, coquettish, while the Anglo-Saxon is plain, coarse, gauche, and ill-tempered? The beauty was married to a long, lean down-Easter, who appeared most jealously attentive to her, occasionally hinting at a return to the curtained bed, where she could escape the admiring glances of strangers. Like her mother, she was able to speak English, but she could not be persuaded to open her mouth. This is a truly Indian prejudice, probably arising from the savage, childish sensitiveness which dreads to excite a laugh; even a squaw married to a white man, after uttering a few words in a moment of épanchement, will hide her face under the blanket.

The half-breed has a bad name in the land. Like the negro, the Indian belongs to a species, sub-species, or variety—whichever the reader pleases—that has diverged widely enough from the Indo-European type to cause degeneracy, physical as well as moral, and often, too, sterility in the offspring. These half-breeds are, therefore, like the mulatto, quasi-mules. The men combine the features of both races; the skin soon becomes coarse and wrinkled, and the eye is black, snaky, and glittering like the Indian's. The mongrels are short-lived, peculiarly subject to infectious diseases, untrustworthy, and disposed to every villainy. The half-breed women, in early youth, are sometimes attractive enough, uniting the figure of the mother to the more delicate American face; a few years, however, deprive them of all litheness, grace, and agility. They are often married by whites, who hold them to be more modest and humble, less capricious and less exacting, than those of the higher type: they make good wives and affectionate mothers, and, like the Quadroons, they are more “ambitious”—that is to say, of warmer temperaments—than either of the races from which they are derived. The so-called red is a higher ethnic type than the black man; so, in the United States, where all admixture of African blood is deemed impure, the aboriginal American entails no disgrace—some of the noblest of the land are descended from “Indian princesses.” ‘The half-breed girls resemble their mothers in point of industry, and they barter their embroidered robes and moccasins, and mats and baskets, made of bark and bulrush, in exchange for blankets, calicoes, glass beads—an indispensable article of dress—mirrors, needles, rings, vermilion, and other luxuries. The children, with their large black eyes, wide mouths, and glittering teeth, flattened heads, and remarkable agility of motion, suggest the idea of little serpents.

The day had been fatiguing, and our eyes ached with the wind and dust. We lost no time in spreading on the floor the buffalo robes borrowed from the house, and in defying the smaller tenants of the ranch. Our host, M. Reynal, was a study, but we deferred the lesson till the next morning.

[1] Punkin (i. e., pumpkin) and corn (i. e., zea maize) are, and were from time immemorial, the great staples of native American agricnlture.

[2] According to Webster, “forks” (in the plural)—the point where a river divides, or rather where two rivers meet and unite in one stream. Each branch is called a “fork.” The word might be useful to English travelers.

[3] The price of the strong light traveling wagon called an ambulance in the West is about $250; in the East it is much cheaper. With four mules it will vary from $750 to #900; when resold, however, it rarely fetches half that sum. A journey between St. Joseph and Great Salt Lake City can easily be accomplished in an ambulance within forty days. Officers and sportsmen prefer it, because they have their time to themselves, and they can carry stores and necessaries. On the other hand, “strikers” —soldier-helps—or Canadian engagés are necessary; and the pleasure of traveling is by no means enhanced by the nightly fear that the stock will “bolt,” not to be recovered for a week, if then.

[4] According to M. Preuss, who accompanied Colonel Frémont’s expedition, “‘ travelers who visited it some years since placed its height at upward of 500 feet,” though in his day (1842) it had diminished to 200 feet above the river.

[5] From the St. Joseph (Mo.) Gazette: “Obituary.—Departed this life, at his residence in this city, on Wednesday, the 29th day of August, 1860, after a long illness, Antoine Robidoux, in the sixty-sixth year of his age. Mr. Robidoux was born in the city of St. Louis, in the year 1794. He was one of the brothers of Mr. Joseph Robidoux, founder of the city of St. Joseph. He was possessed of a sprightly intellect and a spirit of adventure. When not more than twenty-two years of age he accompanied Gen. Atkinson to the then very wild and distant region of the Yellow Stone. At the age of twenty-eight he went to Mexico, and lived there fifteen years. He then married a very interesting Mexican lady, who returned with him to the States. For many years he traded extensively with the Navajoes and Apaches. In 1840 he came to this city with his family, and has resided here ever since. In 1845 he went out to the mountains on a trading expedition, and was caught by the most terrible storms, which caused the death of one or two hundred of his horses, and stopped his progress. His brother Joseph, the respectable founder of this city, sent to his relief and had him brought in, or he would have perished. He was found in a most deplorable condition, and saved. In 1846 he accompanied Gen. Kearney, as interpreter and guide, to Mexico. In a battle with the Mexicans he was lanced severely in three places, but he survived his wounds, and returned to St. Joseph in 1849. Soon after that he went to California, and remained until 1854. In 1855 he removed to New Mexico with his family, and in 1856 he went to Washington, and remained there a year, arranging some business with the government. He then returned to St. Joseph, and has remained here ever since. Mr. Robidoux was a very remarkable man. Tall, slender, athletic, and agile, he possessed the most graceful and pleasing manners, and an intellect of a superior order. In every company he was affable, graceful, and highly pleasing. His conversation was always interesting and instructive, and he possessed many of those qualities which, if he remained in the States, would have raised him to positions of distinction. He suffered for several years before his death with a terrible soreness of the eyes, which defied the curative skill of the doctors; and for the past ten years he has been afflicted with dropsy. A week or two ago he was taken with a violent hemorrhage of the lungs, which completely prostrated him, and from the effects of which he never recovered. He was attended by the best medical skill, and his wife and many friends were with him to the hour of his dissolution, which occurred on Monday morning, at four o’clock, at his residence in this city. He will be long remembered as a courteous, cultivated, agreeable gentleman, whose life was one of great activity and public usefulness, and whose death will be long lamented.”

[6] The dry heat of the prairies in summer causes the wood to warp by the percolation of water, which the driver restores by placing the wheels for a night to stand in some stream. Paint or varnish is of little use. Moisture may be drawn out even through a nail-hole, and exhaust the whole interior of the wood-work.

[7] These remarks are borrowed from a paper by Professor Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, entitled “Meteorology in its Connection with Agriculture.”

The Indian summer is synonymous with our St. Martin’s or Allhallows summer, so called from the festival held on the 11th of November. “The Indians avail themselves of this delightful time for harvesting their corn; and the tradition is that they were accustomed to say they always had a second summer of nine days before the winter set in. It is a bland and genial time, in which the birds, insects, and plants feel a new creation, and enjoy a short-lived summer ere they shrink finally from the rigor of the winter’s blast. The sky, in the mean time, is generally filled with a haze of orange and gold, intercepting the direct rays of the sun, yet possessing enough of light and heat to prevent sensations of gloom or chill, while the nights grow sharp and frosty, and the necessary fires give cheerful forecast of the social winter evenings near at hand.”—-The National Intelligencer, Nov. 26th, 1857, quoted by Mr. Bartlett.