"It was in this Sacramento Valley, just referred to, that a deal of the most lucrative of the early gold mining was done, and you may still see, in places, its grassy slopes and levels torn and guttered and disfigured by the avaricious spoilers of fifteen and twenty years ago. You may see such disfigurements far and wide over California—and in some such places, where only meadows and forests are visible—not a living creature, not a house, no stick or stone or remnant of a ruin, and not a sound, not even a whisper to disturb the Sabbath stillness—you will find it hard to believe that there stood at one time a fiercely-flourishing little city, of two thousand or three thousand souls, with its newspaper, fire company, brass band, volunteer militia, bank, hotels, noisy Fourth of July processions and speeches, gambling hells crammed with tobacco smoke, profanity, and rough-bearded men of all nations and colors, with tables heaped with gold dust sufficient for the revenues of a German principality—streets crowded and rife with business—town lots worth four hundred dollars a front foot—labor, laughter, music, dancing, swearing, fighting, shooting, stabbing—a bloody inquest and a man for breakfast every morning—everything that delights and adorns existence—all the appointments and appurtenances of a thriving and prosperous and promising young city,—and now nothing is left of it all but a lifeless, homeless solitude. The men are gone, the houses have vanished, even the name of the place is forgotten. In no other land, in modern times, have towns so absolutely died and disappeared, as in the old mining regions of California. It was a driving, vigorous, restless population in those days. It was a curious population. It was the only population of the kind that the world has ever seen gathered together, and it is not likely that the world will ever see its like again. For observe, it was an assemblage of two hundred thousand young men—not simpering, dainty, kid-gloved weaklings, but stalwart, muscular, dauntless young braves, brimful of push and energy, and royally endowed with every attribute that goes to make up a peerless and magnificent manhood—the very pick and choice of the world’s glorious ones. No women, no children, no gray and stooping veterans,—none but erect, bright-eyed, quick-moving, strong-handed young giants—the strangest population, the finest population, the most gallant host that ever trooped down the startled solitudes of an unpeopled land. And where are they now? Scattered to the ends of the earth—or prematurely aged and decrepit—or shot or stabbed in street affrays—or dead of disappointed hopes and broken hearts—all gone, or nearly all—victims devoted upon the altar of the golden calf—the noblest holocaust that ever wafted its sacrificial incense heavenward. It is pitiful to think upon. It was a splendid population—for all the slow, sleepy, sluggish-brained sloths staid at home—you never find that sort of people among pioneers—you cannot build pioneers out of that sort of material. It was that population that gave to California a name for getting up astounding enterprises and rushing them through with a magnificent dash and daring and a recklessness of cost or consequences, which she bears unto this day—and when she projects a new surprise, the grave world smiles as usual, and says “Well, that is California all over.”"

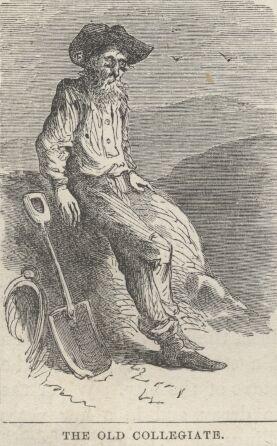

By and by, an old friend of mine, a miner, came down from one of the decayed mining camps of Tuolumne, California, and I went back with him. We lived in a small cabin on a verdant hillside, and there were not five other cabins in view over the wide expanse of hill and forest. Yet a flourishing city of two or three thousand population had occupied this grassy dead solitude during the flush times of twelve or fifteen years before, and where our cabin stood had once been the heart of the teeming hive, the centre of the city. When the mines gave out the town fell into decay, and in a few years wholly disappeared—streets, dwellings, shops, everything—and left no sign. The grassy slopes were as green and smooth and desolate of life as if they had never been disturbed. The mere handful of miners still remaining, had seen the town spring up spread, grow and flourish in its pride; and they had seen it sicken and die, and pass away like a dream. With it their hopes had died, and their zest of life. They had long ago resigned themselves to their exile, and ceased to correspond with their distant friends or turn longing eyes toward their early homes. They had accepted banishment, forgotten the world and been forgotten of the world. They were far from telegraphs and railroads, and they stood, as it were, in a living grave, dead to the events that stirred the globe’s great populations, dead to the common interests of men, isolated and outcast from brotherhood with their kind. It was the most singular, and almost the most touching and melancholy exile that fancy can imagine.—One of my associates in this locality, for two or three months, was a man who had had a university education; but now for eighteen years he had decayed there by inches, a bearded, rough- clad, clay-stained miner, and at times, among his sighings and soliloquizings, he unconsciously interjected vaguely remembered Latin and Greek sentences—dead and musty tongues, meet vehicles for the thoughts of one whose dreams were all of the past, whose life was a failure; a tired man, burdened with the present, and indifferent to the future; a man without ties, hopes, interests, waiting for rest and the end. (Roughing It)

From Page 278-82: The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871

On December 4 he and Steve Gillis arrived at the one-room cabin on Jackass Hill, a mile from Tuttletown in Tuolomne County, where Steve's brothers Jim and William lived with their partner Dick Stoker. According to Dan De Quille, the cabin was “a friendly place of retreat in the mountain wilds for writers desirous of respite from the vanities and vexations of spirit incident to a life of literary labor in San Francisco.” Dan once called it “the headquarters of all Bohemians visiting the mountains.’ ... The cabin was well stocked with books—“Byron, Shakespeare, Bacon, Dickens, & every kind of first-class literature’

Tuttletown had long since become a backwater in the ebb tide of the Gold Rush, moreover. During the 1850s, as Sam told Rudyard Kipling in 1890, the mining camp had boasted “a population of three thousand—banks, fire-brigade, brick buildings, and all the modern improvements. It lived, it flourished, and it disappeared.”

....

After a weeklong excursion to nearby Vallecito immediately after Christmas, Sam returned to Jackass Hill, where he camped until January 22. He traveled that day with Jim Gillis to Angel's Camp in Calaveras County, where Gillis had filed a mining claim, though they were soon confined to their room by the winter rains. “I had a very comfortable time in Calaveras county, in spite of the rain, and if I had my way I would go back there,” Sam declared a month later.

Calaveras possesses some of the grandest natural features that have ever fallen under the contemplation of the human mind—such as the Big Trees, the famous Morgan gold mine which is the richest in the world at the present time, perhaps, and “straight” whisky that will throw a man a double somerset and limber him up like boiled macaroni before he can set his glass down. Marvelous and incomprehensible is the straight whisky of Angel's Camp!

.....

As long as the deluge continued, the men “did nothing all day but sit around the bar-room stove, spit, and ‘swop lies’.” Finally, the rains stopped on February 6 and his comrades were able to pocket mine on the Gillis claim.

Sometime between Stoker's arrival at Angel's Camp on January 30 and February 6, however, in the tavern at ‘Tryon’s Hotel where Sam and Jim Gillis played pool, they heard the bartender Ben Coon, a balding former riverboat pilot, relate the tale of a leaping frog contest, unconsciously imitating the deadpan speaking style of Artemus Ward. “I heard the story told by a man who was not telling it to his hearers as a thing new to them, but as a thing which they had witnessed and would remember,” Sam explained.

He was a dull person, and ignorant; he had no gift as a story-teller, and no invention; in his mouth this episode was merely history—history and statistics; and the gravest sort of history, too; he was entirely serious, for he was dealing with what to him were austere facts, and they interested him solely because they were facts; he was drawing on his memory, not his mind; he saw no humor in his tale, neither did his listeners; neither he nor they ever smiled or laughed; in my time I have not attended a more solemn conference... .[N]one of the party was aware that a first-rate story had been told in a first-rate way, and that it was brimful of a quality whose presence they never suspected—humor.

...

The reputation the anecdote earned for Sam “has paid me thousands of dollars since,” he admitted. By the time he left the California goldfields he had taken notes on two other stories told by Dick Stoker that he would publish in the years to come: “Dick Baker's Cat” in Roughing It and “Jim Baker's Bluejay Yarn’ in A Tramp Abroad (1880),

But he did not strike pay dirt as a pocket miner. In Roughing It, Sam asserted that he, Stoker, and the Gillis brothers “panned up and down the hillsides’ around Jackass Hill “til] they looked plowed like a field” and then “prospected around Angel's Camp” without success. Similarly, he claimed in his autobiography that during his months with the Gillis brothers in northern California “they found nothing, but we had a fascinating and delightful good time trying”—as if he had reunited his old Hannibal gang to dig for gold at the mouth of McDowell's Cave. In fact, there is no evidence Sam performed any more physical labor prospecting for gold in California than he had working his claims in Aurora three years earlier. Will Gillis remembered this period differently; “The nearest approach to any work” that Sam “ever did at mining was when he became my partner at one time for about two weeks.” In his own account, moreover, Gillis located a pocket and extracted about seven hundred dollars in gold over ten days, “I doing the work and Sam superintending.” According to Steve Gillis, “Mark was the laziest man I ever knew in my life, physically. Mentally, he was the hardest worker I ever knew,”

Finally, on February 20, Sam left Angel's Camp with Jim Gillis and Stoker to walk back to Jackass Hill in a snowstorm, ‘the first I ever saw in California, as he remembered. “The view from the mountain tops was beautiful.” Three days later, traveling alone, he left the Gillis cabin via Copperopolis and Stockton for San Francisco, where on February 26 he again registered at the Occidental Hotel. “After a three months’ absence,” he reminisced, “I found myself in San Francisco again, without a cent."

On January 26, 1870, Sam wrote a letter to Jim Gillis announcing his coming marriage to Olivia and recounting remembrances of their Angel's Camp days: SLC to James N. Gillis, 26 Jan 1870