This station, similar in construction to Brigham Young’s Beehive House, stood where the Salt Lake Tribune Building now stands, at 143 South Main. Because of recent street beautification, the monument has been moved to the south. According to Sir Richard Burton, the station was one of the better facilities along the Overland Trail for food and lodging. Horace Greeley and Mark Twain were among the guests. This was a home station for Pony Express riders. It was a long, two-story structure with a veranda in front and a large livestock yard in the rear. A granite monument with bronze plaques marks the location today.

(Expedition Utah)

Salt Lake City was a home station and the last station in Division Three of the Pony Express. This station was listed in the 1861 mail contract as Salt Lake House. The wood frame structure, kept by A. B. Miller, stood at present 143 South Main, the site of the Salt Lake Tribune offices in 1979. The Salt Lake House served as a home station for both stage lines and Pony Express riders. This building stood on the east side of Main Street, between First and Second South, in Salt Lake City.

"Next day we strolled about everywhere through the broad, straight, level streets, and enjoyed the pleasant strangeness of a city of fifteen thousand inhabitants with no loafers perceptible in it; and no visible drunkards or noisy people; a limpid stream rippling and dancing through every street in place of a filthy gutter; block after block of trim dwellings, built of “frame” and sunburned brick—a great thriving orchard and garden behind every one of them, apparently—branches from the street stream winding and sparkling among the garden beds and fruit trees—and a grand general air of neatness, repair, thrift and comfort, around and about and over the whole. And everywhere were workshops, factories, and all manner of industries; and intent faces and busy hands were to be seen wherever one looked; and in one’s ears was the ceaseless clink of hammers, the buzz of trade and the contented hum of drums and fly-wheels."

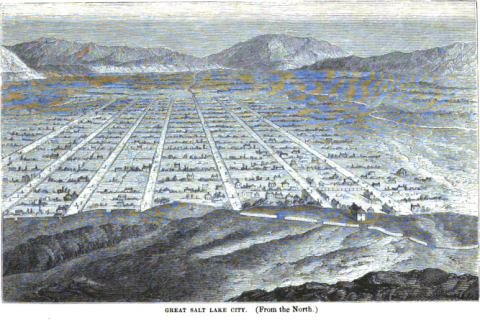

"The city lies in the edge of a level plain as broad as the State of Connecticut, and crouches close down to the ground under a curving wall of mighty mountains whose heads are hidden in the clouds, and whose shoulders bear relics of the snows of winter all the summer long.

Seen from one of these dizzy heights, twelve or fifteen miles off, Great Salt Lake City is toned down and diminished till it is suggestive of a child’s toy-village reposing under the majestic protection of the Chinese wall.

On some of those mountains, to the southwest, it had been raining every day for two weeks, but not a drop had fallen in the city. And on hot days in late spring and early autumn the citizens could quit fanning and growling and go out and cool off by looking at the luxury of a glorious snow-storm going on in the mountains. They could enjoy it at a distance, at those seasons, every day, though no snow would fall in their streets, or anywhere near them."

Horace Greeley:

Salt Lake City wears a pleasant aspect to the emigrant or traveler, weary, dusty, and browned with a thousand miles of jolting, fording, camping, through the scorched and naked American Desert. It is located mainly on the bench of hard gravel that slopes southward from the foot of the mountains toward the lake valley; the houses—generally small and of one story—are all built of adobe (sun-hardened brick), and have a neat and quiet look; while the uniform breadth of the streets (eight rods) and the “magnificent distances” usually preserved by the buildings (each block containing ten acres, divided into eight lots, giving a quarter of an acre for buildings and an acre for garden, fruit, etc., to each householder), make up an ensemble seldom equaled. Then the rills of bright, sparkling, leaping water which, diverted from the streams issuing from several adjacent mountain cañons, flow through each street and are conducted at will into every garden, diffuse an air of freshness and coolness which none can fail to enjoy, but which only a traveler in summer across the Plains can fully appreciate. On a single business street, the post-office, principal stores, etc., are set pretty near each other, though not so close as in other cities ; everywhere else, I believe, the original plan of the city has been wisely and happily preserved. Southward from the city, the soil is softer and richer, and there are farms of (I judge) ten to forty or sixty acres; but I am told that the lowest portion of the valley, nearly on a level with the lake, is so impregnated with salt, soda, etc., as to yield but -a grudging return for the husbandman’s labor. I believe, however, that even this region is available as a stock-range—thousands on thousands of cattle, mainly owned in the city, being pastured here in winter as well. as summer, and said to do well in all seasons. For, though snow is never absent from the mountain-chains which shut in this valley, it seldom lies long in the valley itself.

The pass over the Wahsatch is, if I mistake not, eight thousand three hundred feet above the sea-level; this valley about four thousand nine hundred. The atmosphere is so pure that the mountains across the valley to the south seem but ten or fifteen miles off; they are really from twenty to thirty. The lake is some twenty miles westward; but we see only the rugged mountain known as “ Antelope Island” which rises in its center, and seems to bound the valley in that direction. Both the lake and valley wind away to the north-west for a distance of some ninety miles—the lake receiving the waters of Weber and Bear Rivers behind the mountains in that direction. And then there are other valleys like this, nested among the mountains south and west to the very base of the Sierra Nevada. So there will be room enough here for all this strange people for many years.