Precisely at 8 AM appeared in front of the Patee House - the Fifth Avenue Hotel of St Jo - the vehicle destined to be our home for the next three weeks. We scrutinized it curiously.

See Burton's, The Concord Coach

History of the Overland Stage Coach, Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company

... a stagecoach line ... most well known as the parent company of the Pony Express.

In 1855, the firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell received a two-year contract to supply all the military posts west of the Mississippi River.

On October 28, 1859, the three men entered into a new partnership which assumed the assets and debts of the Leavenworth City & Pike's Peak Express Company. Less than a month later Russell named the new firm the Central Overland California & Pike's Peak Express Company or C.O.C. & P.P Express Co. The new name reflected his hope of securing a daily mail route to California along a central route through the Rocky Mountains.

Russell headed back to New York in December to raise funds and hold off creditors. On January 27, 1860, he wrote his son: "Have determined to establish a Pony Express to Sacramento, California, commencing 3rd of April. Time ten days."

In late 1860 the freight company still had not been paid for their 1857 contract, but with Secretary of War John B. Floyd's personal assurances that they would be paid, they had taken on over $5,000,000 in debt. This debt was on top of the separate debt incurred to set up and run the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co.

In March 1860, Russell, Majors, and Waddell had outfitted a caravan to take supplies to the Army. Due to a number of unforeseen circumstances the caravan was unable to leave until late August. The cost of this delay was high; the men still needed to be paid, the wagon and supplies housed, and the mules and horses fed. Much of the firm's debt came due in mid-summer and they had expected to pay it off with the proceeds from the supply run, but the War Department would only pay upon receipt of goods. The company had to take out more loans to cover the previous debt and further damaged their credit. If the company could secure a government contract for mail, worth $600,000 to $900,000 a year, their financial issues would be solved.

With the success of the Pony Express and the fact that the ocean service was set to expire in June 1860, a contract looked promising. However, Congress adjourned without passing a bill for a central overland mail route. William Russell, after an unsuccessful trip to New York to raise more funds, met with Godard Bailey, a relative of Secretary Floyd. Bailey, perhaps fearing that Floyd, as a guarantor of some of Russell, Majors, and Waddell's debt, would be forced to resign if the firm went bankrupt, agreed to help Russell raise money. Bailey let Russell borrow security bonds from the Indian Trust Fund, which Russell used as collateral for more loans. Bailey was not the owner of the bonds and Russell offered a note in their place that he knew was worth nothing. Russell went back three times to borrow from the Indian Trust Fund. Eventually Bailey's conscience forced him to confess to his part in the scheme and both men were arrested.

The outbreak of the Civil War saved the men from prosecution and they were freed on a technicality.

When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, they destroyed the Butterfield Overland Mail line and effectively cut off communication from California to the east over land. The postmaster general could not simply cancel the contract with the Overland Mail Company and so Congress transferred the route north to keep the mail moving. The C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. supported this move for a number of reasons. The first reason was that the government would subsidize the Pony Express so it could continue to run until the telegraph reached California. The second reason was that the company couldn't afford to run the line alone in its present state, and neither could Overland Mail; therefore the two companies reached an agreement where the C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co. would subcontract to run the mail from St Joseph to Salt Lake City and Overland Mail would run from Salt Lake City to California using C.O.C. & P.P. Express Co's facilities. Considering the state of the company at the beginning of the year this was a favorable development.

With the Civil War begun, the Pony Express was the fastest way to transmit information from east to west and thus found itself in high demand. But the telegraph was catching up quickly, moving east from California and west from Nebraska. By mid August news telegraphed to San Francisco arrived two days before the Pony Express riders. Despite this, the volume of express mail continued to rise. However once the Pony Express stopped receiving government subsidies upon completion of the transcontinental telegraph, the business ran out of cash. Employees dubbed it "Clean Out of Cash and Poor Pay".

The Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company continued to deliver mail from St. Joseph to Salt Lake City for the Overland Mail Company until their contract expired in 1862. On March 21, 1862, Ben Holladay purchased the holdings of the C. O. C. & P. P. Express at public sale for $100,000 and incorporated it into his firm the Overland Stage Company.

Between the Overland Trail and six other routes, Holladay received government subsidies totaling nearly $6 million over a four-year period.

By the end of the California Gold Rush, Wells Fargo was the dominant express and banking organization in the West, making large shipments of gold and delivering mail and supplies. It was also the primary lender of Butterfield Overland Mail Company. In 1860, when Congress failed to pass the annual Post Office appropriation bill, the Post Office was unable to pay Overland Mail Company. This caused Overland to default on its debts to Wells Fargo, allowing Wells Fargo to take control of the mail route.

Six years later, the "Grand Consolidation" united Wells Fargo, Holladay, and Overland Mail stage lines under the Wells Fargo name. Holladay sold his stage routes to Wells Fargo Express in 1866 for $1.5 million.

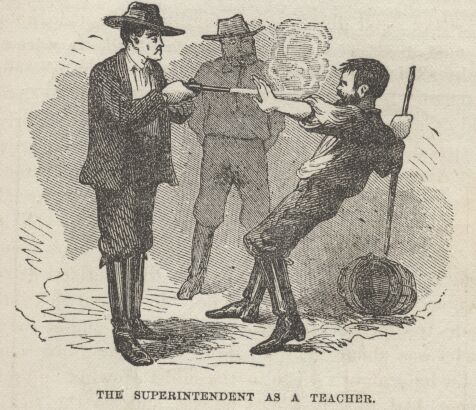

The Superintendent:

"Over each two hundred and fifty miles of road they placed an agent or superintendent, and invested him with great authority. His beat or jurisdiction of two hundred and fifty miles was called a “division.” He purchased horses, mules harness, and food for men and beasts, and distributed these things among his stage stations, from time to time, according to his judgment of what each station needed. He erected station buildings and dug wells. He attended to the paying of the station-keepers, hostlers, drivers and blacksmiths, and discharged them whenever he chose. He was a very, very great man in his “division”—a kind of Grand Mogul, a Sultan of the Indies, in whose presence common men were modest of speech and manner, and in the glare of whose greatness even the dazzling stage-driver dwindled to a penny dip. There were about eight of these kings, all told, on the overland route."

The Conductor:

"Next in rank and importance to the division-agent came the “conductor.” His beat was the same length as the agent’s—two hundred and fifty miles. He sat with the driver, and (when necessary) rode that fearful distance, night and day, without other rest or sleep than what he could get perched thus on top of the flying vehicle. Think of it! He had absolute charge of the mails, express matter, passengers and stage, coach, until he delivered them to the next conductor, and got his receipt for them.

Consequently he had to be a man of intelligence, decision and considerable executive ability. He was usually a quiet, pleasant man, who attended closely to his duties, and was a good deal of a gentleman. It was not absolutely necessary that the division-agent should be a gentleman, and occasionally he wasn’t. But he was always a general in administrative ability, and a bull-dog in courage and determination—otherwise the chieftainship over the lawless underlings of the overland service would never in any instance have been to him anything but an equivalent for a month of insolence and distress and a bullet and a coffin at the end of it. There were about sixteen or eighteen conductors on the overland, for there was a daily stage each way, and a conductor on every stage."

The Driver:

"Next in real and official rank and importance, after the conductor, came my delight, the driver—next in real but not in apparent importance—for we have seen that in the eyes of the common herd the driver was to the conductor as an admiral is to the captain of the flag-ship. The driver’s beat was pretty long, and his sleeping-time at the stations pretty short, sometimes; and so, but for the grandeur of his position his would have been a sorry life, as well as a hard and a wearing one. We took a new driver every day or every night (for they drove backward and forward over the same piece of road all the time), and therefore we never got as well acquainted with them as we did with the conductors; and besides, they would have been above being familiar with such rubbish as passengers, anyhow, as a general thing. Still, we were always eager to get a sight of each and every new driver as soon as the watch changed, for each and every day we were either anxious to get rid of an unpleasant one, or loath to part with a driver we had learned to like and had come to be sociable and friendly with. And so the first question we asked the conductor whenever we got to where we were to exchange drivers, was always, “Which is him?” The grammar was faulty, maybe, but we could not know, then, that it would go into a book some day. As long as everything went smoothly, the overland driver was well enough situated, but if a fellow driver got sick suddenly it made trouble, for the coach must go on, and so the potentate who was about to climb down and take a luxurious rest after his long night’s siege in the midst of wind and rain and darkness, had to stay where he was and do the sick man’s work. Once, in the Rocky Mountains, when I found a driver sound asleep on the box, and the mules going at the usual break-neck pace, the conductor said never mind him, there was no danger, and he was doing double duty—had driven seventy-five miles on one coach, and was now going back over it on this without rest or sleep. A hundred and fifty miles of holding back of six vindictive mules and keeping them from climbing the trees! It sounds incredible, but I remember the statement well enough.:

"The station-keepers, hostlers, etc., were low, rough characters, as already described; and from western Nebraska to Nevada a considerable sprinkling of them might be fairly set down as outlaws—fugitives from justice, criminals whose best security was a section of country which was without law and without even the pretence of it. When the “division- agent” issued an order to one of these parties he did it with the full understanding that he might have to enforce it with a navy six-shooter, and so he always went “fixed” to make things go along smoothly.

Now and then a division-agent was really obliged to shoot a hostler through the head to teach him some simple matter that he could have taught him with a club if his circumstances and surroundings had been different. But they were snappy, able men, those division-agents, and when they tried to teach a subordinate anything, that subordinate generally “got it through his head.”"