In the night we sailed by a most notable curiosity, and one we had been hearing a good deal about for a day or two, and were suffering to see. This was what might be called a natural ice-house. It was August, now, and sweltering weather in the daytime, yet at one of the stations the men could scape the soil on the hill-side under the lee of a range of boulders, and at a depth of six inches cut out pure blocks of ice—hard, compactly frozen, and clear as crystal! (Roughing It)

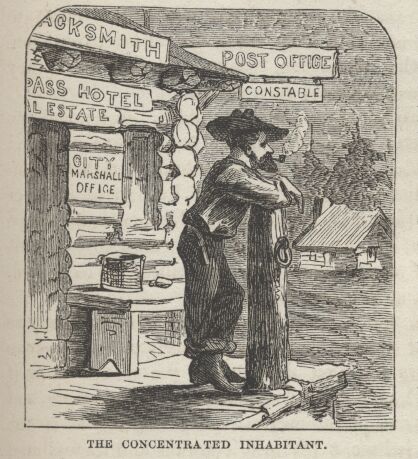

From Orion: Saturday, Aug. 3. Breakfast at Rock Ridge Station, 24 miles from “Cold Spring,” and 871 miles from St. Joseph. A mile further on is “South Pass City” consisting of four log cabins, one of which is the post office, and one unfinished.

See Burton To the Foot of South Pass 19th August and To the South Pass August 20th

(The City of the Saints)

Horace Greeley:

It was midnight of the 3d, when we reached the mailroute station known as the Three-Crossings, from the fact that so many fordings of the Sweetwater (here considerably larger than at its mouth, forty miles or more below) have to be made within the next mile. We had been delayed two hours by the breaking away of our two lead-mules, in crossing a deep water-course after dark—or rather by the fruitless efforts of our conductor to recover them. I had been made sick by the bad water I had drank from the brooks we crossed during the hot day, and rose in a not very patriotic, certainly not a joyful mood, unable to eat, but ready to move on. We started a little after sunrise; and, at the very first crossing, one of our lead-mules turned about and ran into his mate, whom he threw down and tangled so that he could not get up; and in a minute another mule was down, and the two in imminent danger of drowning. They were soon liberated from the harness, and got up, and we went out; but just then an emigrant on the bank espied a carpet-bag in the water—mine, of course—and fished it out. An examination was then had, and showed that my trunk was missing—the boot of the stage having been opened the night before, on our arrival at the station, and culpably left unfastened. We made a hasty search for the estray, but without success, and, after an hour’s delay, our conductor drove off; leaving my trunk still in the bottom of Sweetwater, which is said to be ten feet deep just below our ford. I would rather have sunk a thousand dollars there. Efforts were directed to be made to fish it out; but my hope of ever seeing it again is a faint one. We forded Sweetwater six times yesterday after that, without a single mishap; but I have hardly yet become reconciled to the loss of my trunk, and, on the whole, my fourth of July was not a happy one.

Our road left a southerly bend of Sweetwater after dinner, and took its way over the hills, so as not to strike the stream again till after dark, at a point three miles from where I now write. We passed, on a high divide some miles before we were crossing of the Sweetwater, a low swamp or meadow known as “Ice Springs,” from the fact that ice may be obtained here at any time by digging down some two or three feet into the frosty earth. We met several wagon-loads of come-outers from Mormonism on their way to the states in the course of the afternoon; likewise, the children of the Arkansas people killed two years since, in what is known as the mountain-meadows-massacre. We are now nearly at the summit of the route, with snowy mountains near us in several directions, and one large snow-bank by the side of a creek we crossed ten miles back. Yet our yesterday’s road was no rougher, while it was decidedly better, than that of any former day this side of Laramie, as may be judged from the fact that, with a late start, we made sixty miles with one (six mule) team to our heavy-laden wagon. The grass is better for the last twenty miles than on any twenty miles previously ; and the swift streams that frequently cross our way are cold and sweet. But, unlike the Platte, the Sweetwater has scarcely a tree or bush growing on its banks; but up the little stream on which I am writing, on a box in the mail company’s station-tent, there is glorious water, some grass, and more wood than I have seen so close together since I emerged from the gold diggings on Vasquer’s Fork, five hundred miles away. A snow-bank, forty rods long and several feet deep, Ties just across the brook; the wind blows cold at night; and we had a rain-squall—just rain enough to lay the dust—yesterday afternoon. The mail-agent whom we met here has orders not to run into Salt Lake ahead of time; so he keeps us over here to-day, and will then take six days to reach Salt Lake, which we might reach in four. I am but a passenger, and must study patience.

[This was very likely Rocky Ridge Station, a "Home" Station]