"But Sam had no future in Muscatine. For that matter, neither did Orion. He was half owner of a Whig newspaper, but as soon as he settled there, he had changed his party affiliation from Whig to Republican to signal his opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act.' The act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened the western territories to “popular sovereignty —that is, to settlement by slaveholders. Opponents of slavery, including Orion, were outraged, and passage of the act led inexorably to border ruffians like William Quantrill and to the rehearsal for the Civil War in 'bloody Kansas.'"

See The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871 " Chapter: Journeyman Printer:

Sam returned to St. Louis lasting there only a few months then returning to Keokuk and rejoining his brother, Orion. Sam delivers his first public speech and comes across a book about exploring the Amazon and the unregulated trade in coca.

Sam wrote his brother, Henry, about Brazil:

... Ward and I have held a long consultation, Sunday morning, and the result was that us two have determined to start to Brazil, if possible, in six weeks from now, in order to look carefully into matters there ... and report to Dr. Martin in time for him to follow on the first of March. We propose going via. New York. Now, between you and I and the fence you must say nothing about this to Orion, for he thinks that Ward is to go clear through alone, and that I am to stop at New York or New Orleans until he reports. But that don’t suit me. My confidence in human nature does not extend quite that far. I won’t depend upon Ward’s judgment, or anybody’s [else.—]I want to see with my own eyes, and form my own opinion.

“SLC to Henry Clemens, 5 Aug 1856, Keokuk, Iowa (UCCL 00012).”

In a letter to Jacob H. Burrough in November of 1876, Mark Twain characterized himself from this time:

My Dear Burrough

As you describe hi me I can picture myself as I was, 22 years ago. The portrait is correct. You think I have grown some; upon my word there was room for it. You have described a callow fool, a self-sufficient ass, a mere human tumble-bug, stern in air, heaving at his bit of dung & imagining he is re-modeling the world & is entirely capable of doing it right. Ignorance, intolerance, egotism, self-assertion, opaque perception, dense & pitiful chuckle-headedness—& an almost pathetic unconsciousness of it all. That is what I was at 19–20; & that is what the average Southerner is at 60 to-day. Northerners, too, of a certain grade. It is of children like this that voters are made. And such is the primal source of our government! A man hardly knows whether to swear or cry over it.

I think I comprehend there position there—perfect freedom to vote just as you choose, provided you choose to vote as other people think—social ostracism, otherwise.

Dissatisfied with his position in Orion Clemens’s mismanaged Ben Franklin Book and Job Office and hoping to venture profitably into Brazil, Clemens decided to abandon Keokuk. His own account of his departure, elliptical and influenced by time and imagination, occurs in his autobiography:

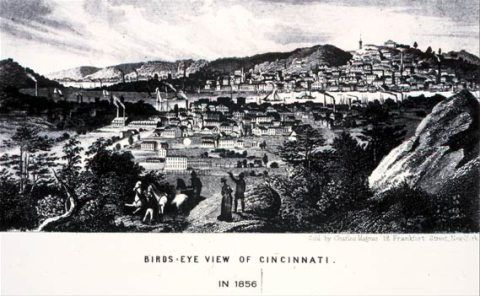

One day in the midwinter of 1856 or 1857—I think it was 1856—I was coming along the main street of Keokuk in the middle of the forenoon. It was bitter weather—so bitter that that street was deserted, almost. A light dry snow was blowing here and there on the ground and on the pavement, swirling this way and that way and making all sorts of beautiful figures, but very chilly to look at. The wind blew a piece of paper past me and it lodged against a wall of a house. Something about the look of it attracted my attention and I gathered it in. It was a fifty-dollar bill, the only one I had ever seen, and the largest assemblage of money I had ever seen in one spot. I advertised it in the papers and suffered more than a thousand dollars’ worth of solicitude and fear and distress during the next few days lest the owner should see the advertisement and come and take my fortune away. As many as four days went by without an applicant; then I could endure this kind of misery no longer. I felt sure that another four could not go by in this safe and secure way. I felt that I must take that money out of danger. So I bought a ticket for Cincinnati and went to that city.

Actually, Clemens left Keokuk in October 1856, not in “midwinter.” He made a brief visit to St. Louis, where he evidently attended the opening day, 13 October, of the St. Louis Agricultural and Mechanical Association Fair and wrote a sketch about it. He also wrote his first Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass letter in St. Louis, on 18 October.

Having spent about a week with his mother and sister, Clemens left St. Louis. It is likely that he departed on 18 October and arrived in Keokuk the following day. He then went on by river packet to Quincy, Illinois, then by train through Chicago and Indianapolis to Cincinnati, probably arriving on 24 October. There he found employment at T. Wrightson and Company, one of the city’s leading printers, where he continued to work into the spring of 1857.

See "Mark Twain in Cincinnati: A Mystery Most Compelling" by William Baker for speculations of Sam Clemens' activities in Concinnati. From pages three and four:

Clemens's official biographer, Albert B. Paine, says Clemens had planned to go directly to Cincinnati from St. Louis, "but a new idea--a literary idea--came to him and he returned to Keokuk." Where did he get the money for that steamer trip and the subsequent train passage to Cincinnati? Perhaps he found fifty dollars, as he reports, although he might have borrowed it from his sister Pamela's husband, William A. Moffett, with the request to keep it a secret; hence the invention of finding fifty dollars. River travel to Cincinnati via Cairo and then east on the serpentine Ohio River, a distance of 600 miles, would have cost only nine dollars, while the trip by railroad via Terre Haute and Indianapolis, a distance of 350 miles, would have cost about fifteen dollars. But parts of the Ohio were too low for steamers in the fall of 1856, though he probably could have made a steamer trip as far as Louisville. And although the trip by railroad would have necessitated three changes of rail lines (the direct 322-mile route was not open until April 1857), the rail route was clearly the logical alternative. He ended up by taking a crazy zig-zag route that cost about thirty dollars (about $25.24 fare plus food, hotel, and porterage). It was a sizeable expense for a man who had been working for five dollars a week plus room and board, even more remarkable since he claims he never got any money at all.

Now it is the dating that concerns us. If I am correct in guessing that Clemens took the Snodgrass letter to Keokuk on the day after it was written, he would have arrived on 19 October. In his eagerness to see Rees he would not have waited longer. Fred Lorch says he spent "a day or two" in Keokuk. If we say two days, 20 and 21 October, that would put him on the river packet to Quincy on 22 October, arriving by train in Chicago that night, where he stayed in "the Massasawit House," entraining for Indianapolis on the 23rd. Then he took "the midnight thunder and lightning train" from Indianapolis to Cincinnati, arriving on the morning of 24 October 1856. If my assumptions are correct, he arrived in the center of the western publishing industry about five weeks before his twenty-first birthday on 30 November.

On 15 April 1857 Clemens took passage for New Orleans on the packet Paul Jones. Probably the “great idea” of the Amazon journey was still alive in his mind as he later claimed, but within two weeks his old ambition to become a Mississippi pilot was rekindled. During daylight watches he began “doing a lot of steering” for Horace E. Bixby, pilot of the Paul Jones, whose sore foot made standing at the wheel painful. Bixby (1826–1912), later a noted captain as well as pilot, recalled after Clemens’s death:

I first met him at Cincinnati in the spring of 1857 as a passenger on the steamer Paul Jones. He was on his way to Central America for his health. I got acquainted with him on the trip and he thought he would like to be a pilot and asked me on what conditions he could become my assistant. I told him that I did not want any assistant, as they were generally more in the way than anything else, and that the only way I would accept him would be for a money consideration. I told him that I would instruct him till he became a competent pilot for $500. We made terms and he was with me two years, until he got his license.

Scharnhorst has a different date for Sam's trip on the Ohio River. See The Life of Mark Twain: The Early Years, 1835-1871, page 93.

Sam paid a sixteen-dollar fare and on February 16, 1857, he finally left Cininnati aboard the Paul Jones, a 353-ton side-wheeler traveling from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. From there he planned to embark on the next ship sailing for Para, Brazil, and the Amazon. He described the steamboat in “Old Times on the Mississippi” as an “ancient tub,” and, following his lead, Paine described it as an “ancient little craft” and Samuel Charles Webster mocked it as the “ramshackle Paul Jones.” But Sam’s description of the ship was another example of his creative (mis)remembering. The ship had been built only two years earlier; it was piloted by one of the most respected officers on the river; and contemporary newspapers praised it as a “magnificent,” ‘first class,” and a “very staunch and pretty packet” with “finely furnished cabins’ and “superb” dining.

Bixby consistently indicated that he and Clemens came to terms either at their first meeting or quite soon after, Mark Twain designated New Orleans as the place where he approached Bixby about becoming his steersman and where they reached an agreement. Clemens’s version is the most romantic, not until the Paul Jones reached New Orleans on [26 April ?] February 28 (DBD) did Clemens learn that he “couldn’t get to the Amazon” : the obstacles were insuperable. But it is reasonable to assume that, before agreeing to instruct him, Bixby would have used the entire trip to New Orleans to test his ability at handling the wheel. It's not likely he would have done so without some idea of Clemens' intent.

Samuel L. Clemens would learn the river and become a Mississippi Riverboat Pilot.