ROUTE 37. DAMASCUS TO BA’ALBEK,

Damascus to Dummar 1 15

Ain Fîjeh 2 45

Sik Wady Barada, Abila 1 40

Zebdâny 3 0

Surghâya 2 0

Ba‘albek, Heliopolis 4 30

Total .. .. . 15 10

This route cannot be accomplished profitably and pleasantly in less than 3 days. The first evening we pitch our tents by the fountain of Fijeh; the second at Surghaya; and by an early start on the third morming we may get into Ba’albek at noon. The objects of special interest are the scenery and sources of the Abana, and the site of Abila. Be it remembered that dragomen and muleteers almost universally try to avoid Fîjeh, because it involves a detour of an hour. They may swear that the road is impassable; that it is infested by robbers; that the village has been burned to the ground. But don’t believe them; go your own route and compel them to go with you. The road is certainly none of the best; but there is many a rougher path daily traversed by muleteers in Lebanon.

We follow the Beyrout road as far as Dummar, where we turn to the rt. and wind for 45 min. among bare chalk hills, almost white as snow. To these succeed the flinty plain of Sahra for nearly an hour more. We then reach the head of a beautiful glen down which we turn to the l., amid terraced vineyards and fig-orchards. Up in the mountain side to the rt. rock tombs may be noticed, one of which has an imperfect Greek inscription. The scenery becomes wilder and grander as we descend. The mountain to the rt. rises in broken cliffs and projections to a height of more than 2000 ft.; while on the l. is a steep gravelly acclivity surmounted by a wall of naked rock. In front is the deep ravine of the Barada filled with foliage, and overshadowed by lofty precipices. The village of Bessîma is perched on a mound on the very brink of the foaming torrent. Immediately below it the river enters a cleft so narrow that there is not space even for a foot-path along its banks. Here may be seen an old aqueduct tunnelled through the side of the cliff; it seems to have been intended to convey water from the fountain of Fijeh to Damascus. It now serves as a pathway of communication between Bessîma and Ashrafîyeh, a small village 1/4 h. down the glen. An old tradition ascribes its construction to some “daughter of a king,” Zenobia perhaps, who wished to convey the limpid waters of ’Ain Fîjeh to Palmyra; though the tradition has found some modern advocates, it deserves no more credit than that which represents the source of the fountains of Tyre as at Baghdad.

We now wind up the sublime glen by a path hewn along the steep bank of the stream. It is everywhere narrow, sometimes rugged, and occasionally dangerous where it passes a projecting cliff on the very brink of the torrent. The winding of the glen affords continued variety of scenery, like the moving pictures of a diorama. No description could convey a full impression of the grandeur of this pass. Leaving behind a limpid fountain with a miniature meadow beside it, we reach the groves and orchards of Fijeh, which line the river, and straggle up the terraces on the steep mountain side. Branches of the walnut cover the path, and poplars rise like spires high above them; while the apricot, apple, and cherry form a dense underwood. We at length reach the hamlet of Fijeh, consisting of some 30 wretched houses, and in 5 min, more we dismount beside the fountain.

The Fountain of Fijeh is one of the largest and most remarkable in Syria. It bursts forth from a narrow cave, under an old temple, at the base of a shelving cliff. The mouth of the cave is small, and partly filled up by massive blocks of stone; through this the pent-up water leaps and foams with a roar like that of a stormy sea. It forms at once a rapid torrent, 30 ft. wide, and 3 or 4 deep, which rushes over a rocky bed for 70 or 80 yds., and then joins the Barada. Though not the highest. Ain Fîjeh is the principal source of the river, its volume being 2 or 3 times that of the other stream. Just over the fountain is a small platform of heavy masonry, and behind it the ruins of a temple some 30 ft. square, with massive walls, but without any kind of ornament. To the rt. of the fountain is a singular building, 37 ft. by 27, open to the S.; the walls are 6 ft. thick, built of huge stones, and it was formerly covered by a vaulted roof. The whole structure is manifestly of remote antiquity.

The valley is here about 200 yds. wide; the bottom along the banks of the stream filled with orchards and poplar groves; above these are a few vineyards, carried up the broken mountain sides as far as man can gain a footing; to these succeed jagged cliffs, which rise to the height of 1000 ft. or more above the river's bed. It is a sweet spot for an encampment. One can spread his carpet upon the little platform over the foaming waters, and muse in peace, lulled by their voice; or look up at the beams of the evening sun slanting down the glen, tipping with gold the tops of the poplars and the projecting cliffs. No officious cicerone will intrude upon his privacy—no sturdy amateur bandit will demand bakhshish. Some village girl in her picturesque costume may pause for a moment to look at the stranger, or offer him a blushing apricot from the little basket she poises so gracefully on her head; but from other visitors he feels secure.

Leaving this wild retreat, we wind along the shelving mountain side, high above the stream. The valley soon expands, and the belt of orchards becomes wider ; while the hills, being less precipitous, are cultivated in terraced patches. The effects of irrigation are strikingly seen. As far up as the canals and ducts are carried all is fresh and verdant; but immediately above the line all is white and parched. White limestone rocks, and a white soil composed of disintegrated limestone, make the hills look more barren than they really are. Passing Deir Mukurrin and Kefr ez-Zeit, we come, in 1 h. 20 min., to Kefr el-’Awamîd, a amall hamlet with a ruin, apparently of a temple, on the acclivity above it. Heavy foundations and a number of columns show a building of some extent and beauty in its palmy days; and still giving a name to the village ‘beside it—Kefr el-’Awamîd, “the village of the columns.” We here cross the river by a modern bridge, and then wind up along the right bank for about 20 min. to Sûk.

Sûk Wady Barada, ABILA.—The situation of this village is picturesque, and the scenery round it exceedingly wild. It stands on the rt. bank of the river in the midst of orchards. Above it the glen intersects the central ridge of Antilebanon; but as it makes a sharp turn, we can only see a huge recess in the mountain side, surrounded by cliffs from 300 to 400 ft. high, dotted with excavated tombs. In the mouth of this recess, looking out on the windings of the valley below, lie the ruins of the ancient city of Abila ; and in the rocks and cliffs overhead are its cemeteries. No buildings remain entire, not even a foundation can be traced. In the modern village, and in the walls of the gardens and orchards, are many large hewn stones and fragments of columns ; portions of the cliff, too, have been cut away as if to give more space for building. On the opposite bank of the river the remains are more extensive, extending along it for 4 m. or more. 10 min. above Sûk a modern bridge of a single arch spans the river, and the road crosses from the rt. to the l. bank. This is the narrowest part of the gorge, and the cliffs that shut it in are not more than 100 ft. apart. Clambering up the mountain side on the left bank, we soon reach one of the most remarkable remains of antiquity—a road cut along and through the rock for a distance of 200 yds. The depth of the cutting is in places more than 20 ft., and the width 12. It terminates at the edge of a cliff, and was formerly carried along on an arched viaduct, or perhaps an embankment, the stones of which now strew the slope below. On the smooth wall of rock in the excavation are tablets containing two Latin inscriptions ; each being repeated, with a slight variation, at the distance of a few yards. The larger and more important one informs us that: the “ Emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus reconstructed the road carried away by the river, the mountain being cut through by the agency of Julius Verus, legate of Syria—at the expense of the inhabitants of Abilene.” The date is not given, but it must be about A.D. 164,

Immediately below the road is an aqueduct, partly hewn and partly tunnelled in the rock: where tunnelled, it is 44 ft. high and 2 wide. Beyond the cliff it is carried along the mountain side, and covered in places with large flat stones. Using the aqueduct as a pathway, we may visit the tombs in the precipice beyond. They are plain chambers, with receptacles in the sides and floors for bodies. They appear to have been closed by stone doors, one of which may be seen beside the river, containing a Greek name. Above the tombs on the top of the mountain are extensive quarries, to which a steep path ascends through a wild gorge. |

On a high hill just above the modern village is a reputed tomb of Abel (Kabr Habîl), nearly 30 ft. long. It is partly covered by a little domed building, and is a place of pilgrimage for Muslems. - A few yards S., on the very brow of the hill, are the ruins of a small temple. The columns of the portico have fallen down the mountain side, and the walls are almost prostrate. Under the E. end is a vault containing three receptacles for bodies,

It has been well known to every scholar of sacred geography for more than 30 years that this is the site of the ancient city of Abila. The ruins, the position, and the inscriptions sufficiently establish the fact. We have already seen (Rte. 36) that about 60 yrs. before the Christian era Ptolemy the son of Mennæus was king of Chalcis. He was succeeded by his son Lysanias, who removed the seat of government to Abila, which for that reason, and to distinguish it from other cities of the same name, was called Abila of Lysanias. Lysanias was murdered through the artifices of Cleopatra, who for a time drew the revenues of the kingdom of Chalcis. Subsequently Abila, with- its province Abilene, was possessed by Philip the tetrarch, mentioned by Luke (iii. 1) ; by Agrippa, the grandson of Herod the Great ; and finally by Herod Agrippa, the last of the Herodian family. (Joseph. Ant. xx. 7, 1.) It became an episcopal see, and its name is frequently mentioned in the decrees of councils.

In A.D. 684 Abila was captured and plundered by the Saracens. The circumstances attending this event are worthy of record, as throwing some light on the origin of its modern name. There lived at that time in a convent in this city a monk widely celebrated for his sanctity and learning. An annual fair, having something of the character of a pilgrimage, was held at his residence at Easter. Christians from far and near regularly assembled to honour the saint, and get gain. The Muslems had just captured Damascus, and were looking round for another opportunity to extend their faith, and secure plunder, when the news reached them of the fair at Abila. Not a moment was lost. The Christian merchants were surprised and stripped of everything. Since that time the name of the place has been Sûk Wady Barada, “The Fair of Wady Barada.” Perhaps we may recognise a trace of the old name in the Kabr Habíl, “Tomb of Abel,” garnished a little by Muslem ingenuity.

On leaving Sûk we enter the sublime glen of the Barada, by which that river cuts through the central ridge of Antilebanon. The cliffs are several hundred ft. high, and the rugged mountains rise over them a thousand more. After winding along it for 3/4 h. we emerge on the beautiful upland plain of Zebdâny. On our left we here see the river tumbling over a ledge of rock 20 ft. high. A few yds. above the waterfall are the ruins of 2 Roman bridges. The road now leads along the side of the plain, which is at first narrow, with the Barada meandering through its centre; but it soon opens out to a breadth of nearly 3 m., and the channel of the river sweeps round to the W., to a little lake at the foot of the opposite mountain range. This is the highest source of the Barada; and is about 1149 ft. above the plain of Damascus. The plain of Zebdâny is in the very centre of Antilebanon. It is basin-shaped, about 8 m. long by 3 wide. The mountain range on the W. is steep and rugged, having an elevation of about 6000 ft.; the opposite ridge is higher, but the features are not so bold. The plain is entirely cultivated, and well watered by numerous fountains, and little rills that descend from the mountain sides. The whole upper end of the plain is covered with groves of mulberries and orchards of fruit-trees, fenced by trim hedges. In the midst of these lies the village of Zebdâny, containing a mixed population of nearly 3000 souls. High up on the right, 1000 ft. above it, is Bludân, picturesquely situated—vineyards clinging to the steep acclivities ; apricots and walnuts, olives and almond trees, blending beautifully their various tinted foliage ; hedges of white roses winding out and in among the trees, and lining the narrow lanes ; and little rills of limpid water leaping and murmuring wherever we turn. And the noble view it commands adds infinitely to the attractions of this mountain village. The highest summit of Antilebanon rises behind it to the height of 7000 ft.; the green plain is spread out beneath it like a carpet; the mountain ranges shutting it in on the right and left, and the snowy cone of Hermon towering in front over a confused mass of lower peaks. Such is Bludân, the paradise of Antilebanon. Its natural attractions, pure air, and excellent water, have caused it to be selected as the summer residence of the Damascus Mission, the British Consul, and a few of the city merchants. The village itself is unusually filthy ; and the people, to say the least, do not deserve the bounties nature has showered upon them.

From Zebdâny we follow up a little streamlet, a winter tributary to the Barada, to near its source beside the hamlet of "Ain Hawar. The plain of Surghaya is now before us, about 3 m. long by 1 broad; stony and only partially cultivated. Here is the watershed between the plains of Damascus and Bukâ’a. The village of Surghaya is beautifully situated at its N.E. end; the highest peaks of Antilebanon towering over it, and a sweet vale, clothed with verdure and sprinkled with trees, winding away to the N. Following the vale for 1/2 h. along the bank of a streamlet, we reach the spot where it falls into Nahr Yahfûfeh, which descends from the mountains on the right, and winds through a sublime gorge westward to the Bukâ’a, conveying its contribution to the Litany. A Roman bridge crosses the Yahfûfeh above the point of junction, showing that we are in the line of the old road from Damascus to Ba’albek. We have now our choice of three paths to the latter town—the first down Wady Yahfûfeh for 1 h., then over a high ridge to Neby Shît, a village containing, as the name implies, the tomb of the “ prophet Seth,” and thence by Bereitân and Taiyibeh: it is long, and part of it very steep. The second across the Roman bridge, and up the mountain by a zigzag path, and then down a dreary slope: this is the shortest way. The third turns to the rt. up the valley to a little village called M’arabûn, passing the ruins of a small temple; then it follows up a long winding glen where the cuckoo and the mavis may be heard among copses of hawthorn. It afterwards crosses a wild ravine called Wady Shabât, and descends gradually a rocky slope to Ba‘albek. This is the line of the Roman road, traces of which are in several places visible; and though not the shortest, it is the easiest and pleasantest.

BA’ALBEK, HELIOPOLIS.

Ba'albek has obtained a world-wide celebrity. The magnificence of its ruins has excited the wonder and admiration of every traveller who has been privileged to visit it. Its temples are among the chefs-d’œuvre of Grecian architecture. For gorgeousness of decoration, combined with colossal magnitude, they stand unrivalled. The temples of Athens may surpass them in strict classic taste and purity of style ; but they fall far short of them in dimensions The wonderful structures of Thebes exceed them in ‘magnitude ; but with the symmetry of their columns, and the richness of their sculptured friezes and doorways, they bear no comparison. The substructions of the Great Temple are themselves entitled to rank high among the wonders of the world. Stones.upwards of 60 ft. long by 13 ft. broad are employed in its construction, and have been raised to a height of more than 20 ft. !

Ba'albek is too poor to afford a hotel. Accommodations may be obtained in some of the private houses but they are not inviting ; and if the weather be favourable the tent is much more comfortable. It may be pitched in the court of the temple, the entrance to which at the S.W. angle, though a little difficult, is quite practicable for laden animals; and the ground within affords a smooth grassy surface. Here we have the splendid structures all round us, and we can look at them in the full blaze of sunshine ; and in the evening, when the level rays tinge the sculptured frieze and volutes of the capitals with gold; and in the pale moonlight, when, perhaps, they present the most striking appearance.

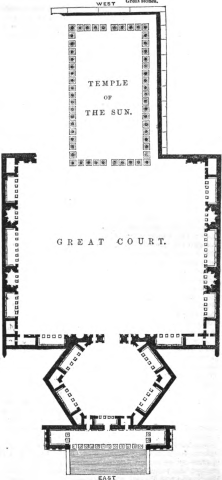

Ba'albek is situated in the plain of Bukâ’a, at the northern end of a low range of bleak hills, about 1 mile from the base of Antilebanon. The city was irregular in form, and encompassed by substantial walls with towers at short intervals. These walls are 2 miles in circumference ; but the modern village only consists of about 100 houses, huddled together without regard to order or convenience, in a corner of the old site. The S.W. angle of the wall, now the only part standing, runs up the end of the ridge, and has a picturesque look with its broken battlements and cracked towers. ½ m. E. of the site is a noble fountain of purest water. It springs up in a large circular basin, surrounded by masonry; beside it is a roofless mosk, and foundations of other buildings. The stream from this fountain runs straight to the village, bordered by green meadows. The whole space within the walls is encumbered with heaps of ruins and rubbish. On the N. side of the village is a large mosk in ruins, containing some beautiful columns of granite and porphyry. But the main attractions of Ba’albek are its 3 temples. The first, which we may call “the Great Temple,” consists of a peristyle, of which only 6 columns remain, 2 courts, and a portico, all standing on an artificial platform, nearly 30 ft. high, and having long vaults underneath. The second, which we may term “the Temple of Jupiter,” occupies a lower platform of its own on the S. side of the former, and only a few ft. distant. A large portion of it is still in good preservation; and it forms by far the most imposing structure in Syria. The relative positions of these 2, with the courts, portico, and substructions of the former, will be seen at a glance on the accompanying plan. The third is “ the Circular Temple,” which stands alone about 200 yds. to the S.E. of the others. Though small, and now, alas! sadly dilapidated, it is a perfect gem. By following me in my descriptions, and taking an occasional glance at the plan, the visitor at Ba’albek will be able to obtain a satisfactory view of these splendid ruins; and I trust also that even the stayer at home may acquire a tolerably clear idea of their character. But let it be fully borne in mind that no description can approach the reality. The exquisite proportions of the columns, which give them the aspect of such airy lightness at a little distance that we cannot credit their vast magnitude till we stand beside them; the elaborate sculptures of the portals, niches, friezes, and lacunari ; the accumulated heaps of enormous shafts, gigantic capitals and architraves, that cover the ground ; and perhaps more than all the Cyclopean masonry of the platform — form a group unequalled in the world of architecture, The mind is overwhelmed by the view. No words could express its feelings. These ruins have been the wonder of past centuries ; and they will continue to be the wonder of future generations, at least until the barbarism of the Turks, and the shocks of earthquakes, have completed the ruin they have commenced.

THE GREAT TEMPLE.—We begin our examination at the portico on the E. side of the outer court. It is 180 ft. long by 37 deep, and consisted of 12 columns between wings ornamented with corresponding pilasters. The floor is elevated 20 ft., and the wall below is built of large undressed stones, indicating that there was originally an immense flight of steps leading up to it. The steps are gone; the columns are gone with the exception of their bases, on 2 of which are the inscriptions given below ; but the wings are almost perfect. The stones of which the latter are composed would make destruction a work of immense labour. Some of them are 24 ft. long! In each wing.on the level of the portico and opening into it, is a chamber 31 ft. by 38, ornamented by pilasters supporting a deep cornice, and intervening niches. The back wall of the portico is also ornamented by pilasters and niches. The whole has been sadly defaced in order to convert it into a fortress. The spaces between the pedestals have been built up and loopholed; and Saracenic battlements have been perched on the top of the wings. Just at the base of the wings are doors opening into the singular vaulted passages that run underneath the whole platform.

A triple gateway, with deep mouldings, opens into the first court, which is in the form of a hexagon, 200 ft. across. On all its sides except the W. were rectangular recesses (exedræ), with 4 columns in front of each. That on the E. formed a vestibule to the entrance from the portico. Between the recesses were smaller chambers. These are now almost completely ruined.

On the western side of the hexagon was a portal 50 ft. wide, and 2 side portals, each 10 ft., opening into the second or great court, immediately in front of the temple itself. It is 440 ft. long and 370 wide, and is encompassed by recesses and niches, which even in their ruin present a picture of singular magnificence. The 2 sides exactly correspond, and in proceeding with our examination we shall take the S., as being in rather better preservation than the other. Next to the gateways on the E. side is a niche 18 ft. wide, apparently intended for a colossal statue. Then comes a rectangular recess (exedræ), with 4 columns in front, like those in the hexagon. Next follows a group of 3 chambers in the angle. On the S. side we have first a rectangular recess with 4 columns in front; then a semicircular one with 2 columns; and next, occupying the middle of this side, a larger rectangular recess with 6 columns, Then follows, as before, in corresponding order, a semicircular exedræ with 2 columns, a rectangular one with 4, and a chamber with an ornamented door next the corner. None of these exedræ are now perfect; a large section at the S.W., and another at the N.E. angle, are destroyed. The columns in front of the exedræ are all gone; the shafts were of red granite, and fragments of them are lying on the ground amid heaps of rubbish. The interior of each exedræ was profusely ornamented with pilasters supporting a richly sculptured entablature, and with niches having either shell tops or pediments. Some of these are still perfect as when completed by the workmen. Over the recesses an uninterrupted entablature, the frieze covered with garlands of fruit and flowers, ran round the court. On the western side of the court near the centre are the remains of a raised platform, on which once stood 6 pedestals in 2 rows, probably for statues.

Fronting this great quadrangle, at its western end, was the temple—a vast peristyle, measuring 290 ft. long, and 160 broad. On each side were 19 columns, and at each end 10; 54 in all. The diameter of the columns at the base is 7 ft. 3 in., and at the top 6 ft. 6 in.; and their height, including base and capital, 75 ft.; over this rises the entablature, 14 ft. more. The shafts are composed of 3 pieces; the base one, the capital one, and the

huge entablature reaching from column to column is one single block! The pieces were fastened together by iron cramps, a foot long and a foot thick ; and sometimes 2 of these were inserted, one round and the other square. “One of the most revolting forms of the ruthless barbarism which these splendid ruins have suffered at the hands of the Turks is seen in the breaking away of the bottom of the columns still standing, in order to obtain these masses of iron! The style of architecture is Corinthian ; and the capitals are designed and executed with remarkable artistic skill. The entablature is scarcely surpassed in the world; the mouldings are deep, and filled up with the egg and dice ornament; the frieze has garlands hung between projections, each of which is adorned with an acanthus leaf and a bust over it. Critics may object to the profusion of sculpture and fretwork, and they may tell us that the whole is not in strictly classic taste; but whatever they may say, the effect is splendid; and one never tires looking at those 6 noble columns, now, alas! the only remnant of the peristyle. The bases of most of the other columns are in their places ; but there is not a trace of a cella, and indeed it is questionable whether the temple was ever completed—if so, it was the largest of its kind in the world next to that of Jupiter Olympus at Athens.

The peristyle stood on massive walls nearly 50 ft. high ; and the appearance of it from the surrounding plain must thus have been magnificent. The eastern wall rested against the platform of the court, from which there was probably an ascent by a flight of steps. The southern wall is nearly covered by rubbish. The northern is open and composed of huge bevelled stones, like those in the Temple at Jerusalem.,

But the greatest wonders of Ba’albek are the immense exterior masses of masonry by which the walls supporting the peristyle are enclosed on the N. side and W. end, at a distance of about 30 ft. These are best seen from the outside. The western wall rises to the level of the bases of the columns, some 50 ft. above the surface of the ground; and in it is seen the layer of 3 enormous stones, so long and so justly celebrated. Of these 1 is 64 ft. long; another 63 ft. 8 in.; and the third 63 ft.—in all 190 ft. 8 in. Their height is 13 ft., and their thickness about the same. They are 20 ft. above the ground, and below them is a layer of 7 others of like thickness. These stones mark the extent of a platform of unknown antiquity; but unquestionably far older than the peristyle; and it was from them the Great Temple took the name by which it was long called, Τρίπετρο, “the Three-stoned.” The northern wall of this ancient platform is only 20 ft. high, and was never completed. The masonry is Cyclopean, but rough —probably the great stone still seen in the neighbouring quarry was intended for it. In this wall are 9 stones, each about 31 ft. long, 13 high, and 9 ft. 7 in. wide.

Such is the Great Temple, with its courts and substructions. The platform on which the courts stand is much too large for the superstructure, and is probably much more ancient: underneath it are long ranges of vaults and corridors with round arches, in which are some Latin inscriptions mostly illegible, and here and there a mutilated bust. This platform may be of Phœnician origin, and perhaps supported a temple long prior to the Roman age.

THE TEMPLE OF JUPITER.—This is at once the most perfect and the most magificent monument of ancient art in Syria. It stands on a platform of its own, beside that of the Great Temple, but considerably lower. It is peripteral and faces the E. Its dimensions are 227 ft. in length, by 117 in breadth ; being thus larger than the Parthenon at Athens, and the portico of the Pantheon at Rome. The style is Corinthian ; and the character of the sculptured ornaments shows that it was coeval, or nearly so, with the Great Temple. The peristyle is composed of 42 columns, 15 on each side and 8 at each end. At the portico was an interior row of 6 fluted columns ; and within these, opposite the ends of the antæ, 2 others. The height of the columns is 65 ft., including base and capital ; and their diameter at the base 6 ft. 3 in., and at the top 5 ft. 8 in. Over this is a richly ornamented entablature about 12 ft. high. The entablature is connected with the walls of the cella by enormous slabs of stone (lacunari); the under part, forming the soffit or ceiling, being slightly concave and exquisitely sculptured. In the centre of each slab is a hexagon with a figure, in high relief, of one or other of .the ancient gods. Round this are 4 smaller rhomboids containing busts with borders of tracery and scrollwork. Most of them are now so much injured as scarcely to be distinguishable. The portico is entirely destroyed, only a few pieces of the shafts remaining in situ; the flight of steps by which it was approached is also destroyed; and the front of the vestibule is encumbered by a wall of Saracenic origin. Most of the columns of the peristyle have fallen, bringing down with them entablature and lacunari. On the S. side 4 remain standing with their entablatures, just adjoining the portico. At the W. end there are 6; and on the N. 9. One shaft has fallen against the S. wall, displacing several stones of the cella, and yet so strongly have the pieces of which it is composed been fastened together that it has remained in that position unbroken for more than a centy. In 4.D. 1751, when Wood and Dawkins made their valuable drawings, the W. end was entire, and 9 columns still existed on the S, side. At that time also there were 9 columns remaining of the Great Temple. The earthquake of 1759 threw down the 3 columns of the Great Temple, and no less than 9 in the peristyle of the Temple of Jupiter.

The dimensions of the cella are 160 ft. long, by 85 wide. In front is a vestibule between antæ 24 1/2 ft. deep. A modern wall is built across it, the only entrance being by a low hole broken through it. Crawling through this, we have before us the gem of the whole structure—the Great Portal. It was 21 ft. wide, and 42 high; but a considerable portion of it is now buried beneath masses of rubbish. The sides are each a single stone, and the lintel is composed of 3 huge blocks. Round the whole runs a border 4 ft. wide, elaborately and delicately sculptured ; representing fruit, flowers, and vine-leaves in high relief. The architrave contains, in addition, little figures, Cupids or Bacchuses, in different attitudes, with bunches of grapes in their hands. Over this is a frieze of scrollwork and acanthus-leaves winding round Cupids; and the whole is finished by a rich cornice. On the soffit of the door is the celebrated figure of the eagle, with a caduceus in his talons, and in his beak the strings of long twisted garlands which extend on each side, and have the opposite ends borne up by flying genii. “The crest shows that this is not the Roman eagle; but, as the same figure is found in the great Temple of the Sun at Palmyra, Volney and others regard it as the oriental eagle, consecrated to the sun.”’ This portal was perfect when sketched by Wood in 1751; but the shock of the earthquake, 8 yrs. afterwards, rent the wall, and the central stone of the lintel sunk down about 2 ft.; in which position it still remains, Though thus shattered, it is one of the most striking and beautiful gateways in the world.

The interior of the cella is richly ornamented. The first compartment, or nave, measuring 98 ft. by 67, has 6 fluted semicolumns on each side, with two niches between them, one below having a scallop top, and one above surmounted by a pediment or tabernacle. On each side of the door are massive pillars,—that on the N. encloses a spiral staircase leading to the top of the building. The only entrance to it is a small opening below, not unlike the hole of a badger. The sanctum, or place for the altar and statue, occupies a space 29 ft. deep at the western end, and was considerably elevated above the floor of the nave, from which it appears to have been separated by a range of columns. Beneath the sanctum are 2 vaulted chambers, and on the staircase leading down to one of them is a Cufic inscription, given by Burckhardt (‘ Travels in Syria,’ p. 13). On the back wall of the sanctum travellers may see how French savans, and a few English and American ones, have made a bold stroke for immortality by the help of a charred stick or a paint-brush. One is reminded of the old proverb, ‘“ Nomina stultorum parietibus hærent.” [The names of fools are stuck on the walls]

The heap of ruins at the S.W. angle of this temple form perhaps one of the most wonderful and striking pictures in the world. Here are tumbled together, in one confused mass, colossal fragments of shafts; huge capitals that look when on the ground out of all proportion with the airy columns that rise up beside them; gigantic architraves, friezes, and ceilings, all exquisitely sculptured. It is over this strange heap we scramble on first entering the sacred precincts. On almost every part of the temples and their courts are fragments of embattled Saracenic walls constructed when the place was converted into a fortress.

THE CIRCULAR TEMPLE stands alone, at the distance of about 300 yds. From the others; it has no connexion with them, but the style of architecture shows that it is of the same age. The cella is a circle, 38 ft. in diameter, and is surrounded by a peristyle of 6 columns, 9 ft. distant from the wall. The entablature which these support is not carried round in a circle, but retreats between each pair of columns nearly to the wall of the cella, forming a kind of semicircular apse, and thus appearing something like radiations from a central nucleus. To complete the peristyle 7 columns would have been required, but one was omitted opposite the door, on each side of which, close to the cella, stands a column, The exterior wall is ornamented with pilasters and large niches between them. The interior is encompassed by two tiers of small columns—the lower tier Ionic, supporting a plain cornice; and the upper tier Corinthian with tabernacles over them. The building was once covered by a domed roof ; but this is now fallen, and the whole walls are greatly shattered. A century ago it was used by the Greek Christians as a ch., but now it is entirely abandoned, and threatens soon to become a heap of ruins,

Most travellers, and even some critical architects, after an examination of these splendid ruins, will feel inclined to concur in the conclusion of Messrs. Wood and Dawkins, to whose enterprise and skill we owe so much —that, “ when we compare the ruins of Baalbek with those of many ancient cities which we visited in Italy, Greece, Egypt, and in other parts of Asia, we cannot help thinking them the remains of the boldest plan we ever saw attempted in architecture.”

On the side of the hill, near the S.W. angle of the city, lie the fragments of a monumental column which was standing till near the close of the past century. Its total height, including pedestal, base, and capital, was 38 ft. It is of the Doric order, and was probably surmounted by a statue. The capital is broad, and pierced by a hole, corresponding to which is a small groove running down the whole shaft, the object of which it is difficult to conjecture. It stood over a sepulchral cave, which is said to have been opened a few years ago by Sir Moses Montefiore. Several sarcophagi were found in the interior. On one of the lids are sculptured, in relief,2 genii holding up large wreaths, and having over them grotesque heads. The lid is now broken to pieces,

Near this column and on the hillside above it are many rock tombs. The walls which enclose this section of the city are constructed of old materials, and many of the stones contain fragments of friezes, and cornices, richly ornamented ; while others have imperfect Greek inscriptions upon them, which are sufficiently tantalizing to the enthusiastic antiquary. “Old Mortality” would have a difficult task before him in such a spot as this. One of them contains the name of Zenodorus; but whether it refer to the robber prince of Trachonitis or not, it is impossible to tell.

From hence we may walk to the quarries, 1/2 m. W. of the ruins, close to the base of the hills. We can here see where the massive stones were obtained; and we can wonder anew how they were conveyed to their places. One enormous block remains, ready hewn, but not quite detached. It seems somewhat odd that all the measurements given of this block differ, and almost every traveller measures it for himself. The reason is, the sides are not regular. My measurement is as follows :—Length, 68 ft.; height, 14 ft. 2 in.; breadth, 13 ft. 11 in. It thus contains above 13,000 cubic ft., and would probably weigh more than 1100 tons, or nearly as much as one of the tubes of the Britannia bridge. Verily there were giants in the earth when such blocks were moved about !

History.—The name, the position, and the inscriptions on the pedestals of the great portico, all concur in proving that this is the Heliopolis of Cœelesyria or Phœnicia, frequently referred to by early geographers and historians, “The name Heliopolis, ‘ City of the Sun’ (probably a mere Greek translation of Ba'al-bek), implies that this city, like its namesake in Egypt,was already consecrated to the worship of the Sun. Indeed the sun was one of the chief divinities in the Syrian and Asiatic worship; and to him was applied in their mythology, as well as to Jupiter and some other gods, the name Baal or Lord. The mythology of Egypt. had a strong influence on that of Syria; and it would not be unnatural to suppose a connexion between the forms of sun-worship in the two countries. Indeed, this is expressly affirmed; and Macrobius, in the 5th centy., narrates that the image worshipped at Heliopolis in Syria was brought from Heliopolis in Egypt.”

At what period or by whom the city was founded is unknown ; but it was probably coeval with the palmy days of Phœnician history. The colossal platform of the temple, and the bevelled masonry under the great peristyle, point to a Phœnician origin ; and we may safely conclude that Ba'albek, “ the city of Baal,” was one of the “ holy places” of that remarkable people,—adopted, renamed, and redecorated, like so many others, by Greeks and Romans in succession. Julius Ceesar made Heliopolis a Roman colony, and during the reign of Augustus it was styled, as we learn from coins, “Col. Julia Augusta Felix Heliopolis.” In the 2nd centy. its oracle was in such repute even at Rome, that the emperor Trajan consulted it previous to his second expedition against the Parthians. It is a remarkable fact that no contemporary historian refers to the erection of the splendid temples whose ruins we have just examined ; and the earliest notice we have of them is the important statement of John Malala of Antioch, a writer of the 7th centy., that “ Ælius Antoninus Pius built at Heliopolis of Phœnicia in Lebanon a great temple to Jupiter, which was one of the wonders of the world.” (Chronogr.) The statement is corroborated by the style of architecture, which is manifestly of that age; and by the fact that Antoninus Pius was one of the most munificent patrons of the cities of Syria. We know assuredly from coins that the temples existed in the time of Septimius Severus (193-211), only some 32 yrs. after the reign of Antonine. One of these coins has on the reverse the figure of a temple with a portico of 10 columns, and another a temple with many columns in a peristyle. These seem to correspond to the greater and lesser temples. The legend upon them is “ Colonia Heliopolis Jovi Optimo Maximo Heliopolitano.”

In addition to all this we have the inscriptions above referred to on the pedestals of 2 columns in the grand portico. The characters are in the long, slender style which began to be used in the reign of Septimius Severus. The two seem to be identical, and have thus been restored by M. de Saulcy :— “M. DITS HELIUPOL. PRO SALUTE DIVI ANTONINI PII FEL, AUG. ET JULIÆ AUG. MATRIS D. N. CASTR. SENAT. PATRIÆ CAPITA COLUMNARUM DUO ÆREA AURO INLUMINATA SUA PECUNIA EX VOTO.” This inscription, therefore, is the written testimonial of a vow made for the health of Antoninus Caracalla, and his mother Julia Domna. As it gives the title Divine to the emperor, it was probably executed towards the close of his reign ; and as no mention is made of Geta, who was assassinated in A.D. 212, we may safely conclude that the date of of the inscription is between the years 212 and 217. It appears that the Great Temple was dedicated to all the gods of Heliopolis—Magnis Diis Heliapolitanis—and was thus a kind of Pantheon in which Baal presided. This same Julia Domna, whose name occurs on the inscription as mother of Caracalla, was wife of Septimius Severus, and daughter of Bassianus, priest of the Sun at Emesa. The inscriptions show that the temple existed in a perfect state in the reign of Caracalla, and had been erected at least previous to that time.

We learn from Macrobius that the Great Temple contained a golden statue of Jupiter, which on festival days was carried about in procession through the streets of the city, something like the images of saints in the cities of the Continent at the present time. Those who carried the idol prepared themselves for the holy service by shaving the head, and vows of chastity. Venus was also one of the deities of Helipolis ; and according to all accounts, was honoured in a way not quite so decent as her father. Licentiousness and superstition were as usual closely linked with intolerance. In the year A.D. 297, during the reign of Diocletian, Gelasinus, a poor Christian convert, formerly an actor, was stoned to death in this city. These evil practices all received a check under the emperor Constantine, who founded here an immense basilica, probably that the ruins of which are still visible in the court immediately in front of the great peristyle. (Euseb. Vit, Const. iii. 58.) During the short reign of Julian (A.D. 361-363) the heathen rites and barbarities were revived ; but in A.D. 379 an end was put to all such scenes of debauchery and violence, when Theodosius ascended the throne. Of him we read in the Paschal Chronicle, that, “ while Constantine only shut up the temples of the Greeks, he destroyed them ; and likewise the temple of Balanios at Heliopolis, the great and renowned, the Trilithon, and converted it into a Christian church.’ The name Balanios is probably a corruption of Baal Helion. Allusion seems to be made here to the Temple of Jupiter, which, from its proximity, may have been considered part of the real Trilithon.

When the city fell into the hands of the Muslems in the 7th centy. Two important changes took place—the old name, Ba’albek, was revived ; and the temples with their courts were converted into a fortress. From a large, flourishing, and splendid city, it has gradually declined, until its temples have become utterly ruinous, and its few hundred inhabitants have sought a home in wretched patchwork houses, amid the prostrate remains of ancient palaces. Ba’albek was an episcopal city from a very early age; and it is still the residence of a bishop of the Greek Church, who exercises authority over a dozen or two Christian families. The great body of the inhabitants are -Metâwileh, a wild and turbulent race ; and their hereditary princes, the Emirs Harfûsh, have for many years been the pests of the country. The way in which the government have dealt with these gentry during the last 20 yrs. Is quite Turkish. They rebelled, were beaten—some of them were captured and banished to Crete; the rest outlawed. The head of the family, left behind, hovered for years about the mountains, maintaining a large bodyguard, and living, of course, by plunder. In 1855 a force of 600 soldiers was sent to seize him, but only succeeded in seizing his donkey. A few weeks afterwards he marched to Damascus at the head of 150 of his people, had an interview with the pasha, obtained the governorship of Ba'albek, and the command of 250 men for the defence of the district! About a year ago one of the banished princes effected his escape from Crete, suddenly appeared in his native place, and summoned around him his old retainers. The prospect of plunder, combined with that attachment for old families which so strongly characterises many of the mountaineers of Syria, brought hundreds to his banner, Funds were wanting, and he levied heavy contributions from the surrounding villages. The sheikh of one village was shot dead because he refused to pay the amount laid upon him; two heads of families in another village had their ears cut off because they attempted to remonstrate. He has now declared war against his kinsman the governor, and by the help of the people of Zahleh has driven him N. to the village of Fîkeh. The government look on in calm indifference. What possible interest can they have in family broils or in the welfare of villages?

Such as wish for a fuller account of the country between Damascus and Ba‘albek, the river Barada (the ancient Abana), and the ridge of Antilebanon, may consult my ‘ Five Years in Damascus.’ The architectural student will find the drawings, plans, and detailed measurements in Wood and Dawkins’ great work by far the most satisfactory. It is just a centy. since it was published, and many changes have occurred in the interval, but no work has appeared to supersede it. The plates in Roberts's ‘Sketches of the Holy Land’ are very beautiful. Dr. Robinson, in his ‘ Later Biblical Researches,’ gives a clear description of the ruins, and a good summary of the history.