Possibly the most difficult leg of their journey, through the arid lands of the Basin and Range Province of the American Southwest, the road from Salt Lake City to Carson City. The Clemens brothers took one week, from August 7th to the 14th. Richard Burton took nearly a month to complete the journey, from September 20 to October 19th of 1860. Their routes were essentially the same until the last portion. Burton took the southern route from Fairview to Carson. By the next year this route was closed due to problems with Indians. The Clemens brothers took what is referred to as the Stillwater Dogleg.

The route over the Rocky Mountains started from Fort Laramie, through South Pass and into Salt Lake City. Sam and Orion passed by Fort Laramie at night, from August 1 to August 5th. Richard Burton took 2 weeks to complete this leg of his journey, from August 14 to August 28.

From the Missouri River to the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains. The road ran through Kansas, Nebraska and into Wyoming. They passed Fort Kearney, Julesburg, also known as Overland City, to Fort Laramie. The Clemens brothers traveled this road between July 26 and August 1, 1861. Richard Burton, between August 7 and August 14, 1860.

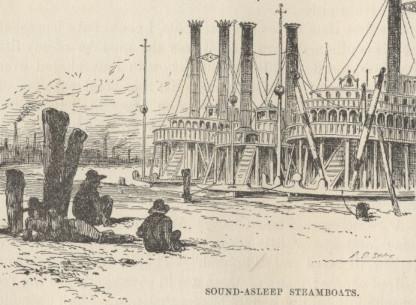

Samuel L. Clemens and Richard Burton both took a steamboat from St. Louis to St. Joseph and neither had much to say about the trip. Burton does address the physical characteristics of the Mississippi River drainage basin and presents arguments as to why the Missouri River should not be considered as the Mississippi's headwaters.

Steamboat: CITY OF MEMPHIS

Subscribe to

© 2026 Twain's Geography, All rights reserved.