DAMASCUS,

Damascus can now boast of 2 Hotels.The old one, sometimes dignified by the name of Hôtel de Palmyre, but only known in the city as the Locanda, is in the “Street called Straight.” It is neither clean nor comfortable, and its proprietor has gained such a reputation for Arab tricks, that nothing but stern necessity would drive any unfortunate traveller to it, or detain him in it. It is said to have undergone some little improvement since the establishment of its rival. The new Hotel—El Locanda el-Jedid, or Locanda Mellûk—is one of the finest houses of the city, and has been fitted up with considerable taste. Two of its saloons are among the best specimens of modern Damascus architecture. There is some little historical interest, too, about the place, for it was formerly occupied by ’Aly Agha (whose daughter is still the proprietor), Secretary of the Treasury to Ibrahîm Pasha. Poor ’Aly was a great friend of the Egyptian General, but, being suspected of treachery in opening up a correspondence with the Sultân, he was deprived of his head one morning. The hotel gives fair promise, and is well situated, nearly

in the centre of the old city. Its proprietors, the brothers Mellûk, are also silk-merchants, and have the largest and best assortment of Damascus scarfs, shawls, &c., in the city.

The British Consul, James Brant, Esq., has his residence and offices in the Muslem quarter, close to the Great Mosk. All letters for travellers should be addressed to his care, and called for. Letters for England may be forwarded by the Consular post, which leaves every alternate Monday in time to meet the Wednesday’s French steamer from Beyrout to Alexandria. There is also an English dromedary-mail to Baghdad every fortnight on the arrival of the post from Beyrout. The Turkish post for Beyrout leaves every Monday and Thursday at sunset, and arrives every Tuesday and Friday evening. For Constantinople there is an overland Tartar post viâ Aleppo, every Wednesday ; and the mail from Constantinople is due every Tuesday.

There are no English banking or mercantile houses in Damascus. Bills on London can easily be negotiated in the offices of several native and foreign merchants; but at a loss of 3 or 4 per cent. The best way of obtaining money is to advise the banker in Beyrout, and draw upon him in Turkish liras, or other known gold or silver coin, for what may be needful. To draw in piastres would entail a loss of at least 2 per cent.

English Service is conducted every Sunday at 12 o’clock in the chapel of the Presbyterian Mission.

Houses in the city are scarce, and rents high, having nearly doubled within the last 5 years. A comfortable house cannot now be obtained for less than from 5000 to 8000 piastres a year—always paid in advance. Most of those that are to be let are half ruinous; the tenant supplies the money for repairs, which is counted up in the rent. All the necessaries of life are as dear as in England, with the single exception of bread. Servants are scarce and bad, while their wages, at least to Franks, re very high. A man calling himself a cook gets from Il. to Il. 10s. A month; and should he happen to know anything of the science, as the French would term it, he will demand double. Tailors and shoemakers are skilful enough in Arab habiliments, but they make a sad caricature of anything European.

The Bazaars of Damascus have long been celebrated: and they are among the best in the East—no mongrel affairs like those of Cairo and Constantinople, but thoroughly Oriental. Long ranges of open stalls, on each side of narrow covered lanes, with a bearded, turbaned, robed figure squatting in the corner of each as composedly as if he had been placed there for show, like the piles of silks that rise up on each side of him. How these men can sit on their heels during the long day, on a spot not more than 18 in. square, is of course a mystery to stiff-legged Europeans. Each trade has its own quarter or section in the immense network of bazaars, and thus we run in succession through the Mercers’ Bazaar, the Tailors’ Bazaar, the Spice Bazaar, the Tobacco Bazaar, the Shoe Bazaar, the Silversmiths’ Bazaar, the Clog Bazaar, the Book Bazaar, the Saddlers’ Bazaar, and the “Old Clo’” Bazaar—turbaned heads and long-robed figures in them all. All the costumes of Asia are here, pushing along the crowded thoroughfares, struggling with panniered donkeys and strings of mules and camels. We see costumes of every fantastic form that tailors could invent, many gaudy and gorgeous as an open sunflower; but the only real wonder among them all is an orthodox English hat. Everything else passes unnoticed, but it attracts universal attention. The flower-potted Derwish stares at it; the Persian, with his furred sugar-loaf, a yard in length, exclaims Mashallah ; the little Turk, with his red nightcap stuck on the back of his bullet head, looks up at it in amazement; village sheikhs, who seem to have got their whole bed-clothes wrapped round their heads, stop to gaze at the phenomenon; Bedawin peer at it from underneath their flame-coloured kefiyehs—yet there is no disrespect. Something like awe appears to be mixed up with wonder, as if each beholder saw round the black nondescript the old Scotch motto, “ Nemo me impune lacessit.”

The bazaars are well stocked: Indian muslins, Manchester prints, Persian carpets, Lyons silks, Damascus swords, Birmingham knives, amber mouthpieces, antique china-ware, Cashmere shawls, French ribbons, Mocha coffee, Dutch sugar—all mingled together. Those who have a taste for curiosities, such as old arms, porcelain, &c., ought to visit the Sûk el-Arwâm, “Greek Bazaar,” near the gate of the palace. Be it remembered that 5 or 6 times the value of the article is usually asked, and accompanied by an oath that no other man but yourself could buy it for the money. To make a bargain with these gentry needs more patience than most Englishmen are gifted. With, and the consequence is, those who do buy are generally ‘“fleeced.” The silk scarfs, shawls, and other goods usually purchased by travellers, will be found in greatest variety in the magazine of the brothers Mellûk, proprietors of the new hotel. The Bulâds are also highly respectable silk-merchants. Their magazine is in Khan el-’Amûd. Large Persian carpets may be obtained of Mr. Freije in Khan As‘ad Pasha, who is one of the most influential and honourable of the Christian merchants.

The situation of Damascus, and the general features of the surrounding country, have already been described. (See above, Rte. 32.) The city stands in the plain, 1 ½ m. from the base of the lowest ridge of Antilebanon. The plain has an elevation of about 2200 ft. above the sea, and is covered with vegetation and foliage. The ridge consists of barren chalk hills, almost white as snow in summer, and in winter of a dull grey colour—running from the base of Hermon in a direction N.E. by E. Their average elevation above the plain is about 600 ft.; but just opposite the city a round-backed hill rises to a height of 1500 ft., and is crowned by a little ruin called Kubbet en-Nasr, ‘the Dome of Victory.” Along the base of this hill lies the large straggling village of Salahîyeh, usually reckoned a suburb of Damascus; and a little to the W. of it the Barăda issues from the mountains by a sublime gorge, and flows due E. through the plain, dividing the city into two unequal parts. Damascus occupies one of those sites which nature seems to have intended for a great perennial city : its beauty stands unrivalled, its richness has passed into a proverb, and its supply of water is unlimited, making fountains sparkle in every dwelling.

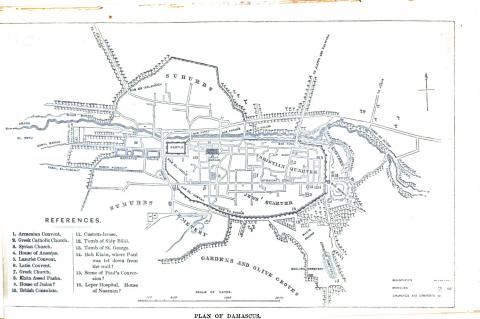

The Old City—the nucleus of Damascus—is on the S. bank of the river. It is of an irregular oval form, encompassed by a rickety wall, and having the massive castle projecting somewhat at its N.W. corner. Its greatest diameter is marked by the “Street called Straight,” which runs from W. to E., and is an English mile in length. In this part are the principal buildings, including the Great Mosk, Khan As’ad Pasha, the Christian churches, &c. Here, too, the Christians reside, clustering round the E. gate. The Jews adjoin them on the S. On the N. bank of the river, adjoining the castle, is a large suburb, extending up the gentle slope towards Salahîyeh. This may be called the Turkish quarter, as a large number of the best houses are occupied by officers of the government, civil and military. At the W. end of the old city is another large suburb, including the long range of barracks, the beautiful mosk and hospital of Sultan Selim, and the courts of justice. Adjoining this, |and extending away southward in a straight line for nearly 2 m., is the Meidin, the largest suburb of all. Through the Meidân runs a wide street, terminating at Buwâbet Ullah, The Gate of God,” through which the pilgrim caravan annually passes on its way to Mekka. It might rather be called “ the Gate of Death,” for hundreds of those who pass through it never return.

The population of Damascus is about 150,000. Of these 129,000 are Muslems, 15,000 Christians, and 6000 Jews. This estimate includes the village of Salaîiyeh, in which there are from 10,000 to 12,000 Inhab., a large number of whom are Kurds.

The principal manufactures of the city are silks, which are exported to Egypt, Baghdad, and Persia; coarse woollen cloth for the abbas, or cloaks, almost universally worn by the peasants of Syria and the Bedawîn; cotton cloths; gold and silver ornaments ; arms, &c. In addition to supplying the wants of the whole population between the southern part of the Hauâan and Hums, the city carries on an extensive trade with the Bedawîn of the eastern desert. The extensive bazaars are always crowded with people and merchandize; and on Friday, the great market-day, it is almost impossible to pass through them. On the arrival of the pilgrim caravan going to and returning from Mekka, the city presents a gay and animated appearance. The vast numbers of Hajys in their picturesque and quaint costumes— Persians, Kurds, Circassians, Anatolians, Turks—all grouped together, and shouting in their different languages; the strange wares they have imported for sale, for each Hajy is a merchant for the time being ; and perhaps more than all the influx of wild Bedawîn who have been brought to the city to escort the caravan on its long desert journey—these form a picture which the world could not match.

Damascus is the real capital of Syria, and the largest city in Asiatic Turkey. Its pasha ranks with the first officers of the empire, because he is not only governor of the province, but also Emir el-Haj, “Prince of the Pilgrim Caravan”—it being part of his duty to accompany, when possible, the caravan to Mekka. The pashalic of Damascus extends from Hamah on the N. to Petra on the S., and embraces the whole inhabited country E. of the Jordan valley, the Bukâ’a, and the Orontes. The city is also the head-quarters of the army of Syria, and the residence of the Seraskier or Commander-in-chief, who is always a Mushir, “ Field Marshal.”’

The History of Damascus reaches away back into the misty regions of antiquity. Josephus affirms that the city was founded by Uz the son of Aram, and great-grandson of Noah. We have no reason to doubt the fact. The family of Aram colonized north-eastern Syria, and gave it the name by which it is universally called in Scripture, ARAM (rendered in the English translation Syria: see Jud. x. 6; 2 Sam. viii. 6, xv. 8; 1 Kings x. 29; Isa. vii. 2; Ezek. xvi. 57, &c.). The distinguishing appellation also of this section of country in Old Testament history is Aram-Damesk, “Aram of Damascus” (2 Sam. vill. 6; 1 Chron. xviii. 6); hence the words of Isaiah, “the head of Syria is Damascus” (vii. 8). The natural highway from southern Mesopotamia, the cradle of the human race, across the desert to Syria, is by the great fountains of Palmyra and Kuryetein. The earliest wanderers westward after the dispersion of Babel would thus be brought to the banks of the Abana. Such a site would at once be occupied, and when occupied would never be deserted.

….

Perhaps the most remarkable fact connected with the history of this city is, that it has flourished under every change of dynasty, and under every form of government. It may truly be called the perennial city. Its station among the capitals of the world has been wonderfully uniform. The presence of royalty never seems to have greatly advanced its internal welfare, nor did their removal cause decay or even decline. It has never rivalled in the numbers of its population, nor in the splendour of its structures, a Nineveh, a Babylon, or a Thebes; but neither has it resembled them in the greatness of its fall, nor in the desolation of its ruins. It has existed and prospered alike under Persian despotism, Grecian anarchy, and Roman patronage; and it exists and prospers still, despite Turkish oppression and misrule. It is like an oasis amid the desert of ancient Syria. It has survived generations of cities that have in succession risen up around it, and passed away. While they all lie in ruins, Damascus retains the freshness and vigour of youth.

...