Mark Twain and his party arrived in Darjeeling Saturday, February 15, 1896. He lectured at the Darjeeling Town Hall that evening and slept in Sunday morning while Livy and Clara went to see the mountains. Later that day he socialized at the Planter's Club and did some site seeing. Livy and Clara started on their return to Calcutta. Twain followed the next day, Monday, February 17.

Ian Strathcarron's visit to Darjeeling stands in stark contrast to Twain's:

As we have been following Twain’s Grand Tour around India the political situation has been as stable for us now as it was for him then. India then had to contend with rule by the Raj but he was there at a peaceful point midway between the two great revolts, the Sepoy Uprising of 1857 and the post-World War 2 Gandhian Uprising that led to Independence in 1947. India now has to contend with rule by a particularly vile set of embezzling politicians, but if it is a scamocracy—as the equally corrupt Indian media insists on calling it—it is also a democracy in rude health.

The exception to this rule now is in the area around Darjeeling which is seeking its own independence, not from India but from the state of West Bengal. Calling itself Gorkhaland to reflect the indigenous Nepalese Gurkha population and lying across the ridges and valleys of the Himalayan foothills, this famously beautiful area has been in turmoil—and a downward spiral—since 1986. What once proudly hailed itself the Queen of the Hills is now an unplanned, overgrown, shabby, ugly, poor and edgy spread of fear and doom. The tourists have mostly disappeared, frightened off by the uncertainty of the transport strikes and the crumbling infrastructure, taking their tourism to more welcoming and accommodating Himalayan destinations. (Page 125).

From Following the Equator:

Up there we found a fairly comfortable hotel, the property of an indiscriminate and incoherent landlord, who looks after nothing, but leaves everything to his army of Indian servants. No, he does look after the bill—to be just to him—and the tourist cannot do better than follow his example. I was told by a resident that the summit of Kinchinjunga is often hidden in the clouds, and that sometimes a tourist has waited twenty-two days and then been obliged to go away without a sight of it. And yet went not disappointed; for when he got his hotel bill he recognized that he was now seeing the highest thing in the Himalayas. But this is probably a lie.

After lecturing I went to the Club that night, and that was a comfortable place. It is loftily situated, and looks out over a vast spread of scenery; from it you can see where the boundaries of three countries come together, some thirty miles away; Thibet is one of them, Nepaul another, and I think Herzegovina was the other. Apparently, in every town and city in India the gentlemen of the British civil and military service have a club; sometimes it is a palatial one, always it is pleasant and homelike. The hotels are not always as good as they might be, and the stranger who has access to the Club is grateful for his privilege and knows how to value it.

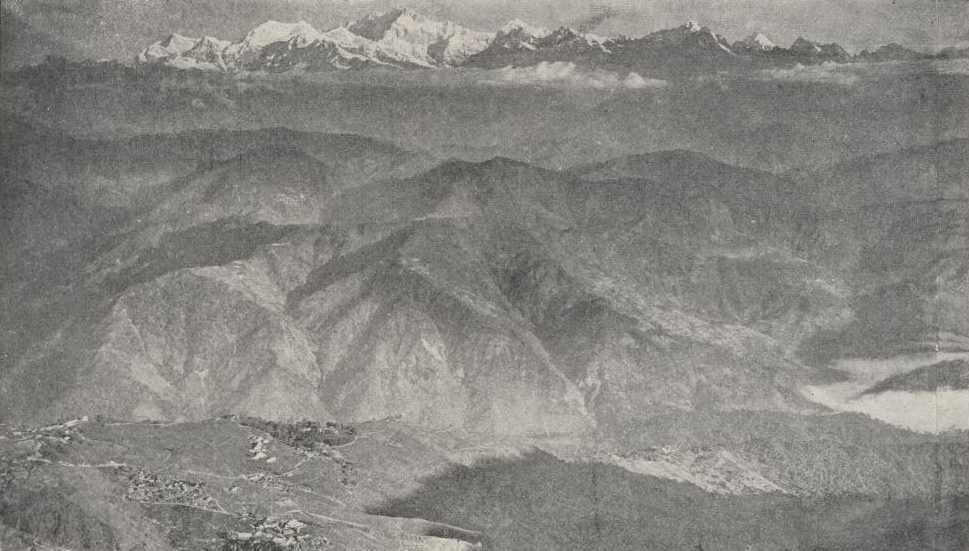

Next day was Sunday. Friends came in the gray dawn with horses, and my party rode away to a distant point where Kinchinjunga and Mount Everest show up best, but I stayed at home for a private view; for it was very cold, and I was not acquainted with the horses, any way. I got a pipe and a few blankets and sat for two hours at the window, and saw the sun drive away the veiling gray and touch up the snow-peaks one after another with pale pink splashes and delicate washes of gold, and finally flood the whole mighty convulsion of snow-mountains with a deluge of rich splendors.

Kinchinjunga's peak was but fitfully visible, but in the between times it was vividly clear against the sky—away up there in the blue dome more than 28,000 feet above sea level—the loftiest land I had ever seen, by 12,000 feet or more. It was 45 miles away. Mount Everest is a thousand feet higher, but it was not a part of that sea of mountains piled up there before me, so I did not see it; but I did not care, because I think that mountains that are as high as that are disagreeable.

I changed from the back to the front of the house and spent the rest of the morning there, watching the swarthy strange tribes flock by from their far homes in the Himalayas. All ages and both sexes were represented, and the breeds were quite new to me, though the costumes of the Thibetans made them look a good deal like Chinamen. The prayer-wheel was a frequent feature. It brought me near to these people, and made them seem kinfolk of mine. Through our preacher we do much of our praying by proxy. We do not whirl him around a stick, as they do, but that is merely a detail.

The swarm swung briskly by, hour after hour, a strange and striking pageant. It was wasted there, and it seemed a pity. It should have been sent streaming through the cities of Europe or America, to refresh eyes weary of the pale monotonies of the circus-pageant. These people were bound for the bazar, with things to sell. We went down there, later, and saw that novel congress of the wild peoples, and plowed here and there through it, and concluded that it would be worth coming from Calcutta to see, even if there were no Kinchinjunga and Everest.