We had a refreshing rest, there in Delhi, in a great old mansion which possessed historical interest. It was built by a rich Englishman who had become orientalized—so much so that he had a zenana. But he was a broadminded man, and remained so. To please his harem he built a mosque; to please himself he built an English church. That kind of a man will arrive, somewhere. In the Mutiny days the mansion was the British general's headquarters. It stands in a great garden—oriental fashion—and about it are many noble trees. The trees harbor monkeys; and they are monkeys of a watchful and enterprising sort, and not much troubled with fear. They invade the house whenever they get a chance, and carry off everything they don't want. One morning the master of the house was in his bath, and the window was open. Near it stood a pot of yellow paint and a brush. Some monkeys appeared in the window; to scare them away, the gentleman threw his sponge at them. They did not scare at all; they jumped into the room and threw yellow paint all over him from the brush, and drove him out; then they painted the walls and the floor and the tank and the windows and the furniture yellow, and were in the dressing-room painting that when help arrived and routed them.

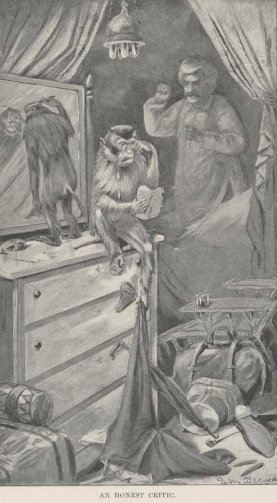

Two of these creatures came into my room in the early morning, through a window whose shutters I had left open, and when I woke one of them was before the glass brushing his hair, and the other one had my note-book, and was reading a page of humorous notes and crying. I did not mind the one with the hair-brush, but the conduct of the other one hurt me; it hurts me yet. I threw something at him, and that was wrong, for my host had told me that the monkeys were best left alone. They threw everything at me that they could lift, and then went into the bathroom to get some more things, and I shut the door on them.

From The Indian Equator:

EVENTS CONSPIRED TO make Mark Twain’s visit to Delhi a short one. Firstly, his schedule was still recovering from the two-week sick leave in Jaipur, delaying pre-booked Talks in Lahore and Rawalpindi76; secondly, he himself was still recovering from his illness in Jaipur and wasn’t in the physical or mental mood for more than cursory sightseeing, and one can only presume that Clara and Smythe were also still wheezy; thirdly, he had no Talk planned in Delhi and so no reason not to move on swiftly; fourthly, Delhi was suffering from “smallpox & water famine threatened”; fifthly, Delhi was still a quaint, provincial, cultureless city compared to the commercial capital, Bombay, and the administrative capital Calcutta; and lastly, they had every intention to make a more leisurely return to Delhi on their way back to Calcutta when he and the city should be in better health. As bad luck had it, the return trip was never made and so his twenty-four hours in Delhi was only a flying visit, albeit one made in some style residing in some style at the only mansion on top of the only hill.

His party arrived from Jaipur at midnight—nine and a half hours late—at what was the old Delhi railway station, which was then being transformed into the Old Delhi Railway Station we see today. In fact it is now being transformed again with a heavy investment in digital signs, CCTV and even—praise the Lord—a coat of paint. Only the red-coated porters have remained the same down the ages: in Twain’s time they were called “coolies” as they still call themselves today. But whether they are coolies or porters their numbers are declining, put out of business by wheely luggage and voracious overpricing, often right under a sign giving the correct rate—half a dollar a bag. Even twenty years ago Indians traveled with their own bedding, it not being expected that hotels or hosts would provide any; another nail in the coolie coffin.(page 188)

For the late arriving Twain party it was bed-time. They trotted in their tongas past the sites they would see the next day: Kashmere Gate, Nicholson’s grave, Civil Lines, up Delhi’s only hill to The Ridge, past the 1857 War Memorial and so on to the mansion in which they were staying. It was quite a place, in quite a spot, with quite a history. The Delhi of twenty million now and the Delhi of half a million then is built on the plains, all flatlands but with one exception, a small hill in the center called, reasonably enough, The Ridge. In 1830 the British Indian enthusiast William Fraser built a fabulous white Palladian mansion on top of The Ridge; it was indeed the mansion on the hill and was occupied in 1896 by the Twain party’s hosts, Mr. and Mrs. Burne of the Bank of Bengal; bankers clearly did as well than as they do now. Twain remembered it as “a great old mansion which possessed historical interest. It was built by a rich Englishman who had become orientalized—so much so that he had a zenana. But he was a broadminded man, and remained so. To please his harem he built a mosque; to please himself he built an English church. That kind of a man will arrive, somewhere. In the Mutiny days the mansion was the British general’s headquarters. It stands in a great garden—oriental fashion—and about it are many noble trees.”

It is still here—after a fashion. It has now been absorbed, swamped, by the enormous, sprawling, filthy Hindu Rao Hospital whose turn it now is to occupy the prime location in Delhi. The main part of the old mansion is now the Plastic Surgery Ward; the annex, where the zenana would have been, is the Endoscopy Unit. The building itself could certainly use some plastic surgery; the introduction of any kind of endoscope into its foundations would probably cause it to collapse.

(page 191)