From Orion: 4 P. M., arrived on the summit of “Big mountain,” 15 miles from Salt Lake City, when the most gorgeous view of mountain peaks yet encountered, burst on our sight.

From Burton Echo Kanyon, August 24th and The End—Hurrah! August 25th.

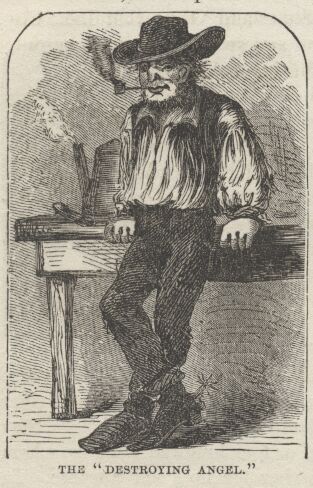

Twain, of course, had a different impression of the "Destroying Angel" Ephe Hanks than did Burton:

..., we changed horses, and took supper with a Mormon “Destroying Angel.”

..., we changed horses, and took supper with a Mormon “Destroying Angel.”

“Destroying Angels,” as I understand it, are Latter-Day Saints who are set apart by the Church to conduct permanent disappearances of obnoxious citizens. I had heard a deal about these Mormon Destroying Angels and the dark and bloody deeds they had done, and when I entered this one’s house I had my shudder all ready. But alas for all our romances, he was nothing but a loud, profane, offensive, old blackguard! He was murderous enough, possibly, to fill the bill of a Destroyer, but would you have any kind of an Angel devoid of dignity? Could you abide an Angel in an unclean shirt and no suspenders? Could you respect an Angel with a horse-laugh and a swagger like a buccaneer?

There were other blackguards present—comrades of this one. And there was one person that looked like a gentleman—Heber C. Kimball’s son, tall and well made, and thirty years old, perhaps. A lot of slatternly women flitted hither and thither in a hurry, with coffee-pots, plates of bread, and other appurtenances to supper, and these were said to be the wives of the Angel—or some of them, at least. And of course they were; for if they had been hired “help” they would not have let an angel from above storm and swear at them as he did, let alone one from the place this one hailed from.

From Orion: Arrived at Salt Lake City at dark, and put up at the Salt Lake House,. There are about 15,000 inhabitants. The houses are scattering, mostly small frame, with large yards and plenty of trees. High mountains surround the city. On some of these perpetual snow is visible. Salt Lake City is 240 miles from the South Pass, or 1148 miles from St. Joseph.

Horace Greeley:

We soon after struck off up a rather steep, grassy water-course which we followed to its head, and thence took over a “divide” to the head of another such, on which our road wound down to “East Cañon Creek,” a fair, rapid trout-brook, running through a deep, narrow ravine, up which we twisted, crossing and recrossing the swift stream, until we left it, greatly diminished in volume, after tracking it through a mile or so of low, swampy. timber, and frequent mud-holes, and turned up a little runnel that came feebly brawling down the side of a mountain. The trail ran for a considerable distance exactly in the bed of this petty brooklet—said bed consisting wholly of round, water-worn granite bowlders, of all sizes, from that of a pigeon’s egg up to that of a potash-kettle; when the ravine widened a little, and the trail wound from side to side of the watercourse as chances for a foothold were proffered by one or the other. The bottom of this ravine was poorly timbered with quaking-asp, and balsam-fir, with some service-berry, choke-cherry, mountain currant, and other bushes; the whole ascent is four miles, not very steep, except for the last half-mile; but the trail is so bad, that it is a good two hours’ work to reach the summit. But, that summit gained, we stand in a broad, open, level space on the top of the Wahsatch range, with the Uintah and Bear Mountains on either hand, forming a perfect chaos of wild, barren peaks, some of them snowy, between which we have a glance at a part of the Salt Lake Valley, some thirty miles distant, though the city, much nearer, is hidden by intervening heights, and the lake is likewise concealed further to the right. The descent toward the valley is steeper and shorter than the ascent from the side of Bear River—the first half-mile so fearfully steep, that I judge few passengers ever rode down it, though carriage-wheels are uniformly chained here. But, though the southern face of these mountains is covered by a far more luxuriant shrubbery than the northern, among which oaks and maples soon make their appearance for the first time in many a weary hundred miles. None of these seem ever to grow into trees; in fact, I saw none over six feet high. Some quaking-asps, from ten to twenty-five feet high, the largest hardly more than six inches through, cover patches of these precipitous mountain-sides, down which, and over the low intervening mountain, they are toilsomely dragged fifteen or twenty miles to serve as fuel in this city, where even such poor trash sells for fifteen to twenty dollars per cord. The scarcity and wretchedness of the timber—(I have not seen the raw material for a decent ax-helve growing in all my last thousand miles of travel)—are the great discouragement and drawback with regard to all this region. The parched sandy clay, or clayey sand of the plains disappeared many miles back; there has been rich, black soil, at least in the valleys, ever since we crossed Weber River; but the timber is still scarce, small, and poor, in the ravines, while ninety-nine hundredths of the surface of the mountains is utterly bare of it. In the absence of coal, how can a region so unblest ever be thickly settled, and profitably cultivated ? .

The descent of the mountain on this side is but two miles in length, with the mail company’s station at the bottom. Here (thirteen miles from the city, twenty-seven from Bear River) we had expected to stop for the night; but our new conductor, seeing that there were still two or three hours of good daylight, resolved to come on. So, with fresh teams, we soon crossed the “little mountain ”—steep, but hardly a mile in ascent, and but half a mile in immediate descent—and ran rapidly down some ten miles through the narrow ravine known as “ Emigration Cañon,” where the road, though much traversed by Mormons as well as emigrants and merchant-trains, is utterly abominable; and, passing over but two or three miles of intervening plain, were in this city just as twilight was deepening into night.