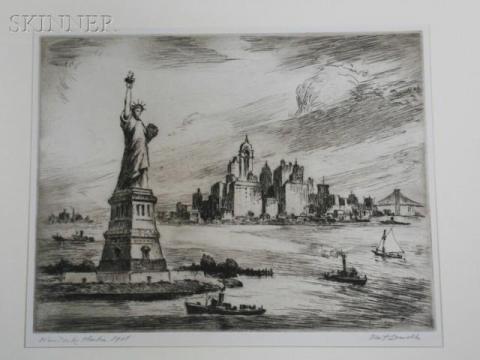

Sam's view of New York City, 1853:

My boarding house is more than a mile from the office; and I can hear the signal calling the hands to work before I start down; they use a steam whistle for that purpose. I work in the fifth story; and from one window I have a pretty good view of the city, while another commands a view of the shipping beyond the Battery; and the “forest of masts,” with all sorts of flags flying, is no mean sight. You have everything in the shape of water craft, from a fishing smack to the steamships and men-of-war; but packed so closely together for miles, that when close to them you can scarcely distinguish one from another.

Of all the commodities, manufactures—or whatever you please to call it—in New York, trundle-bed trash—children I mean—take the lead. Why, from Cliff street, up Frankfort to Nassau street, six or seven squares—my road to dinner—I think I could count two hundred brats. Niggers, mulattoes, quadroons, Chinese, and some the Lord no doubt originally intended to be white, but the dirt on whose faces leaves one uncertain as to that fact, block up the little, narrow street; and to wade through this mass of human vermin, would raise the ire of the most patient person that ever lived. In going to and from my meals, I go by the way of Broadway—and to cross Broadway is the rub—but once across, it is the rub for two or three squares. My plan—and how could I choose another, when there is no other—is to get into the crowd; and when I get in, I am borne, and rubbed, and crowded along, and need scarcely trouble myself about using my own legs; and when I get out, it seems like I had been pulled to pieces and very badly put together again.

“SLC to Jane Lampton Clemens, 31 Aug 1853, New York, N.Y. (UCCL 02712).” In Mark Twain’s Letters, 1853–1866. Edited by Edgar Marquess Branch, Michael B. Frank, Kenneth M. Sanderson, Harriet Elinor Smith, Lin Salamo, and Richard Bucci. Mark Twain Project Online. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. 1988, 2007. Mark Twain Project

Sam Returned to New York January 12, 1867:

From an Editorial narrative following 15 Dec 1866:

He stayed for nearly three weeks at the Metropolitan Hotel, ...

New York itself had greatly changed since the first time Clemens saw it, in the summer of 1853, “when I was a pure and sinless sprout.” For one thing, it was more expensive: you could pay as much as “$30 a week for the same sort of private board and lodging you got for $8 and $10 when I was here thirteen years ago.” It was also more spread out, more populous—and, of course, colder. From the time of his arrival the temperature hovered around 25⁰F, and a heavy snowfall snarled the city on 17 January. A New York correspondent of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin said on 24 January that he had met Mark Twain “a few days after his arrival” and

found him shivering and chattering his teeth at the “damnation cold weather,” and complaining of the “infernal long distances” he had to travel in getting about the city from one place to another. He said he had already frozen two of his teeth, had corns on all his fingers, and a gum-bolt on each heel, and he almost regretted that he had ever wandered away from the clear skies, the balmy atmosphere, and the umbrageous shades of the Washoe country.... but it will, doubtless, be gratifying intelligence to his numerous friends on the Pacific Coast to learn that he bears up nobly under these trials and smiles unconcernedly at them as a true humorist should. In proof of this I need only state, that as I was about parting with him I said: “Marcus, will you smile?” whereat, without the least hesitation, he replied: “W-a-l, it [’]s s-o d-a-r-n-a-t-i-o-n c-o-l-d I d-o-n-t c-a-r-e if I do.” (“Gossip from New York,” letter dated 24 Jan, San Francisco Evening Bulletin, 19 Feb 67, 1)

Probably on the night of 9 December Clemens “shot off to New York,” arriving the following morning (17 Dec 70 to Fairbanks). His presence was quickly noted: the New York Herald reported that “Mark Twain, the great humorist, has come to the city from Buffalo, and is now stopping at the Albemarle Hotel” (“Personal Intelligence,” 11 Dec 70, 6), and the New York Tribune listed him among its “Prominent Arrivals” (12 Dec 70, 8).

On 10 December Clemens must have begun conferring with Sheldon and Company about the pamphlet—published as Mark Twain’s (Burlesque) Autobiography and First Romance, but not until March 1871—and in the succeeding days tried to speed its production by locating Edward F. Mullen, an illustrator he wanted for it. Also on 10 December, or soon after, he met with Charles Henry Webb to resolve their differences over The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, And other Sketches. Clemens received an accounting of the costs of production and a report of the sales since 1867 and bought the copyright back from Webb.

But business did not occupy all of Clemens’s time in New York. At the Albemarle, a “very elegant hotel” at 1101 Broadway, at the junction of Fifth Avenue and Twenty-fourth Street, Clemens enjoyed a respite from domestic concerns and “smoked a week, day & night” (Miller, 70; 19 Dec 70 to Twichell). He may have attended “Dan Bryant’s new minstrel hall on the north side of 23rd Street, west of Sixth Avenue,” where on 11 December a dramatization of his Jumping Frog story, starring “Little Mac,” a dwarf, in the title role, went on the bill (Odell, 9:76–77). Called an “attractive feature” by the New York Herald, the skit was performed throughout the remainder of December and was reprised in April 1871 (New York Herald: “Music and the Drama,” 12 Dec 70, 5; “Amusements,” 10–31 Dec 70; Wilson 1870, 30). It is unlikely that Clemens authorized this production, but its evident popularity conceivably influenced his determination to exploit the story anew.

Editorial narrative following 3 December 1870 to James Redpath

Throughout his life, Sam spent a great deal of time in New York City. I was curious as to how he got around in the city. I found this:

Mass transit emerged in NYC with the “horse bus” or “Omnibus” in the late 1820’s as the city’s first mode of mass land transportation. An over-sized stagecoach of sorts pulled along by horses could accommodate a dozen or so people and regularly ran up and down Broadway. When people who were riding wanted to get off, they pulled on a little leather strap that was connected to the ankle of the driver!

Horse drawn transport continued, but the next step in the evolution was to install embedded iron or steel tracks, designed to carry more people and offer a smoother ride than before. The horse-drawn streetcar debuted in 1832 along Fourth Avenue and the Bowery in Manhattan. Running from the Lower East Side to Union Square, it was opened by a company called the New York and Harlem Railroad, which had ambitions (eventually realized) of connecting New York (today’s Lower Manhattan) with suburban Harlem. That first streetcar was called the John Mason, named for the President of Chemical Bank and one of the wealthiest New Yorkers, who was also a co-founder of the railroad company. Believe it or not, this humble but groundbreaking (literally, as the tracks were embedded in the ground) transportation line is the direct forefather of today’s Metro-North Railway system which carries millions of passengers each years from Grand Central north not just to Harlem but the Bronx, Connecticut, Westchester, and Upstate New York.

Health concerns about horses following the Equine Influenza outbreak of 1872, the slowness of horse carriages, and new technology led to more innovative developments.

In 1883 New York City’s first steam-driven Cable Car emerged, which ran until 1909 when electric trolleys hit the urban scene of all five boroughs. The basbeall team in Brooklyn was so-named because of the enthusiastic fans that had to “dodge” the traffic en route to the stadium (in fact, the team’s original name was “The Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers,” which was later shortened).

The electric streetcar system might have survived the competition of the marketplace because of it’s comparable efficiency for intracity movement. But the automobile industry did not want competitive forms of travel. From the 1920’s to the 1950’s automobile interests bought streetcar systems and worked to substitute rubber-tire vehicles for trolleys.

One Hundred Twenty Five Years of NYC Streetcars Started in the Village

- Sandwich Islands Tours

- Innocents Across the Atlantic

- Innocents Abroad

- A Restless Type Setter

- Buffalo to New York City - 1853

- St. Louis to New York: 1853

- New York City: 1853-54

- Crossing the Peninsula

- New York and the Mid West

- Sandwich Islands Lectures in New York - 1867

- Business in the States

- Delaware Lackawanna & Western Railroad

- February 21, 1885

- From Hartford to Geneva

- Innocents Go Home Again

- Crossing the Peninsula, Westward - Spring 1868

- The End of 1869

- Our Fellow Savages Tour

- January of 1870, New York

- January and February 1872

- Three Speeches Tour

- Departing the US

- Bound for Europe

- November 18 and 19, 1884

- February 1885

- Twain-Cable Tour

- More Business Back in the States

- A Return to Florence

- Rescued by Rogers

- Eight Atlantic Ocean Crossings

- New York City 1900-1901

- To The Person Sitting in Darkness

- November 1884

- Return to the US

- Return to the Mississippi River Valley

- Dublin, NH - Summer of 1906

- Hartford House

- Summer at Branford, CT, Elmira and Quarry Farm - 1881

- Missouri, 1902