There is nothing pretty about an Indian village—a mud one—and I do not remember that we saw any but mud ones on that long flight to Allahabad. It is a little bunch of dirt-colored mud hovels jammed together within a mud wall. As a rule, the rains had beaten down parts of some of the houses, and this gave the village the aspect of a mouldering and hoary ruin. I believe the cattle and the vermin live inside the wall; for I saw cattle coming out and cattle going in; and whenever I saw a villager, he was scratching. This last is only circumstantial evidence, but I think it has value. The village has a battered little temple or two, big enough to hold an idol, and with custom enough to fat-up a priest and keep him comfortable. Where there are Mohammedans there are generally a few sorry tombs outside the village that have a decayed and neglected look. The villages interested me because of things which Major Sleeman says about them in his books—particularly what he says about the division of labor in them. He says that the whole face of India is parceled out into estates of villages; that nine-tenths of the vast population of the land consist of cultivators of the soil; that it is these cultivators who inhabit the villages; that there are certain "established" village servants—mechanics and others who are apparently paid a wage by the village at large, and whose callings remain in certain families and are handed down from father to son, like an estate. He gives a list of these established servants: Priest, blacksmith, carpenter, accountant, washerman, basketmaker, potter, watchman, barber, shoemaker, brazier, confectioner, weaver, dyer, etc. In his day witches abounded, and it was not thought good business wisdom for a man to marry his daughter into a family that hadn't a witch in it, for she would need a witch on the premises to protect her children from the evil spells which would certainly be cast upon them by the witches connected with the neighboring families.

The office of midwife was hereditary in the family of the basket-maker. It belonged to his wife. She might not be competent, but the office was hers, anyway. Her pay was not high—25 cents for a boy, and half as much for a girl. The girl was not desired, because she would be a disastrous expense by and by. As soon as she should be old enough to begin to wear clothes for propriety's sake, it would be a disgrace to the family if she were not married; and to marry her meant financial ruin; for by custom the father must spend upon feasting and wedding-display everything he had and all he could borrow—in fact, reduce himself to a condition of poverty which he might never more recover from.

It was the dread of this prospective ruin which made the killing of girl-babies so prevalent in India in the old days before England laid the iron hand of her prohibitions upon the piteous slaughter. One may judge of how prevalent the custom was, by one of Sleeman's casual electrical remarks, when he speaks of children at play in villages—where girl-voices were never heard!

The wedding-display folly is still in full force in India, and by consequence the destruction of girl-babies is still furtively practiced; but not largely, because of the vigilance of the government and the sternness of the penalties it levies.

In some parts of India the village keeps in its pay three other servants: an astrologer to tell the villager when he may plant his crop, or make a journey, or marry a wife, or strangle a child, or borrow a dog, or climb a tree, or catch a rat, or swindle a neighbor, without offending the alert and solicitous heavens; and what his dream means, if he has had one and was not bright enough to interpret it himself by the details of his dinner; the two other established servants were the tiger-persuader and the hailstorm discourager. The one kept away the tigers if he could, and collected the wages anyway, and the other kept off the hailstorms, or explained why he failed. He charged the same for explaining a failure that he did for scoring a success. A man is an idiot who can't earn a living in India.

Major Sleeman reveals the fact that the trade union and the boycott are antiquities in India. India seems to have originated everything. The "sweeper" belongs to the bottom caste; he is the lowest of the low—all other castes despise him and scorn his office. But that does not trouble him. His caste is a caste, and that is sufficient for him, and so he is proud of it, not ashamed. Sleeman says:

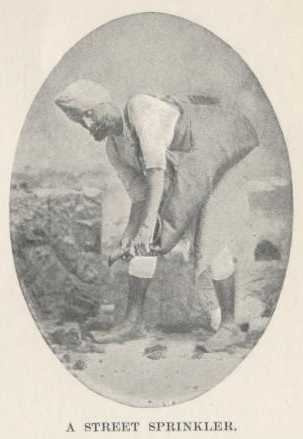

"It is perhaps not known to many of my countrymen, even in India, that in every town and city in the country the right of sweeping the houses and streets is a monopoly, and is supported entirely by the pride of castes among the scavengers, who are all of the lowest class. The right of sweeping within a certain range is recognized by the caste to belong to a certain member; and if any other member presumes to sweep within that range, he is excommunicated—no other member will smoke out of his pipe or drink out of his jug; and he can get restored to caste only by a feast to the whole body of sweepers. If any housekeeper within a particular circle happens to offend the sweeper of that range, none of his filth will be removed till he pacifies him, because no other sweeper will dare to touch it; and the people of a town are often more tyrannized over by these people than by any other."

"It is perhaps not known to many of my countrymen, even in India, that in every town and city in the country the right of sweeping the houses and streets is a monopoly, and is supported entirely by the pride of castes among the scavengers, who are all of the lowest class. The right of sweeping within a certain range is recognized by the caste to belong to a certain member; and if any other member presumes to sweep within that range, he is excommunicated—no other member will smoke out of his pipe or drink out of his jug; and he can get restored to caste only by a feast to the whole body of sweepers. If any housekeeper within a particular circle happens to offend the sweeper of that range, none of his filth will be removed till he pacifies him, because no other sweeper will dare to touch it; and the people of a town are often more tyrannized over by these people than by any other."

A footnote by Major Sleeman's editor, Mr. Vincent Arthur Smith, says that in our day this tyranny of the sweepers' guild is one of the many difficulties which bar the progress of Indian sanitary reform. Think of this:

"The sweepers cannot be readily coerced, because no Hindoo or Mussulman would do their work to save his life, nor will he pollute himself by beating the refractory scavenger."

They certainly do seem to have the whip-hand; it would be difficult to imagine a more impregnable position. "The vested rights described in the text are so fully recognized in practice that they are frequently the subject of sale or mortgage."

Just like a milk-route; or like a London crossing-sweepership. It is said that the London crossing-sweeper's right to his crossing is recognized by the rest of the guild; that they protect him in its possession; that certain choice crossings are valuable property, and are saleable at high figures. I have noticed that the man who sweeps in front of the Army and Navy Stores has a wealthy South African aristocratic style about him; and when he is off his guard, he has exactly that look on his face which you always see in the face of a man who is saving up his daughter to marry her to a duke.

It appears from Sleeman that in India the occupation of elephant-driver is confined to Mohammedans. I wonder why that is. The water-carrier ('bheestie') is a Mohammedan, but it is said that the reason of that is, that the Hindoo's religion does not allow him to touch the skin of dead kine, and that is what the water-sack is made of; it would defile him. And it doesn't allow him to eat meat; the animal that furnished the meat was murdered, and to take any creature's life is a sin. It is a good and gentle religion, but inconvenient.